Introduction

A drug interaction (DI) occurs when a substance disrupts the activity of a drug when both are administered simultaneously.1 Such interactions represent a crucial category of preventable adverse drug events (ADEs),2 with incidence rates spanning from 3% to 30% as supported by multiple studies. Typically, interactions among drugs manifest as drug-drug interactions, but they can also extend to interactions between drugs and food or herbs, all of which have the potential to modify the bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the administered drug, resulting in either toxicity or therapeutic failure. 3 Alarmingly, investigations have revealed that 10%–20% of DIs have dire consequences, leading to patient hospitalization. 4

Preventing and anticipating DIs hinges on understanding their mechanisms and leveraging clinical expertise to ascertain whether inhibitory or inductive factors may give rise to clinically significant DIs. 5 In situations where multiple drug treatments are indispensable for high-risk patients managing chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, depression, or congestive heart failure with three or more medications, the decision to combine drugs must carefully weigh the potential benefits against the risk of clinically significant drug-drug interactions. This assessment should also consider the availability of alternative treatments as advised by the treating physician. 6

A common misconception exists among the general populace that natural herbs and foods are inherently safe. However, altering their consumption habits can lead to drug interactions, counteracting the effects of medications. This misperception often arises from a lack of knowledge and awareness regarding the active ingredients present in these substances. 7 Approximately one-third of adults in the Western world use herbal remedies, often without informing their healthcare providers. 8 Awareness of the foods that patients consume is pivotal for physicians when selecting medications and adjusting treatment regimens, as certain foods may delay or reduce drug absorption. 9 Therefore, it is advisable to consult a physician regarding the timing of food consumption and medication intake. 10 In today's healthcare landscape, drug-food interactions pose substantial challenges during drug therapy. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) has established standards regarding drug-nutrient interactions, mandating healthcare professionals to counsel their patients about these interactions. 11 Thus, physicians are called upon to exercise vigilance across various practice settings and provide guidance to patients regarding potential food-drug interactions. 4

The constant influx of new drugs into the market has led to a rising number of reports on new drug-drug and food-drug interactions. 12 This phenomenon is exacerbated by the increasing proportion of the aging population and the frequent necessity of polypharmacy—prescribing multiple drugs to address comorbidities. Consequently, it is no longer feasible for physicians to solely rely on their past medical knowledge to evade potential drug interactions. 13 As healthcare practitioners assume a pivotal role in safeguarding patients from the perils associated with potential drug interactions, particularly in cases involving drugs with narrow therapeutic indices, 6 understanding the extent to which these providers can identify such interactions and develop effective management strategies is imperative for reducing adverse events. Regrettably, the available literature indicates that the knowledge of drug interactions among practicing physicians is often inadequate. 14

Hence, this study was conducted to evaluate the factors influencing common drug interactions, leveraging knowledge, attitude, and awareness among healthcare practitioners in their everyday clinical practice.

Methodology

The present study was across-sectional study, carried out from November 2019 to April 2020 in tertiary care hospital and Research Centre Pt. B.D. Sharma PGIMS, Rohtak (Haryana), India. Survey forms were distributed by drop-and-collect methods to randomly selected 300 doctors including professors, senior residents, and post-graduates of various specialties in the outdoor-patient department. As the study was questionnaire based, approval was obtained from the head of each department involved in the survey. Individual consent was also taken from all the participants. Complete confidentiality was maintained, no name or any information regarding identity of particular participant was asked.

The sample size was calculated from the Raosoft software. The minimum sample size calculated was 260 with 95% confidence level, 5% accepted a margin of error. The final sample size taken was 300 participants.

Study Questionnaire

A self-administered questionnaire was used as a tool for data collection, which have been developed by reviewing available questionnaires in the literature. A pilot study was done in a small group of subjects to assess the clarity and understanding of questions. The questionnaire was also reviewed by experts for validation. The reliability of survey tool was evaluated using Cronbach alpha.

The questionnaire was divided into four domains: Domain 1 was the demographic characteristics of all participants, including gender, age, and healthcare specialty. Domain 2 was the evaluation of knowledge of DIs. Domain 3 was the evaluation of attitude towards the preferred method for detection of DIs and domain 4 was evaluation of awareness doctors towards DIs. At the end of the questionnaire, an open-ended item was added to allow participants to further add any comments.

Statistical analysis

The acquired data underwent statistical analyses utilizing SPSS 22.0. Descriptive analysis was employed to calculate the frequencies of responses for all demographic items and questions related to knowledge, attitude, and awareness. The chi-square test was utilized to investigate the association between the demographic data, knowledge level, attitude, and awareness variables. A significance level of P-value <0.05 was deemed as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed among practitioners, but only 264 questionnaires found suitable for analysis (the completion rate = 88%), as shown in Table 1 and others were found partially incomplete, due to lack of time among practitioners in the OPD department.

|

Characteristics |

N (%) |

|

Sex: |

|

|

Male |

142 (53.7%) |

|

Female |

122 (46.2%) |

|

Age: |

|

|

25-34yrs |

142 (53.7%) |

|

35-44yrs |

69 (26.1%) |

|

45-54yrs |

42 (15.9%) |

|

>55yrs |

11 (4.1%) |

|

Health care Specialties: |

|

|

Anesthesia |

13 (4.9) |

|

Cardiology |

08 (3.0%) |

|

Dermatology |

25 (9.4%) |

|

Emergency medicine |

35 (13.2%) |

|

Neurosurgery |

09 (3.4%) |

|

Medicine |

39 (14.7%) |

|

Obstetrics and gynecology |

23 (8.7%) |

|

Oncology |

05 (1.8%) |

|

Ophthalmology |

15 (5.6%) |

|

Orthopedics |

12 (4.5%) |

|

Otolaryngology |

11 (4.1%) |

|

Pediatrics |

28 (10.6%) |

|

Psychiatric |

17 (6.4%) |

|

Surgery |

17 (6.4%) |

|

Urology |

07 (2.6%) |

Knowledge of Drug interactions

Drug - drug interactions

In the examination of practitioners' awareness regarding drug interactions, a substantial majority (94%, n=188) of the study participants demonstrated a clear understanding of clinically significant drug interactions. The ramifications of drug interactions were recognized to be contingent upon factors such as drug dosage, health status, and age. Notably, over half of the respondents (53%, n=106) expressed the belief that the geriatric patient population faces a higher susceptibility to developing drug interactions, followed by pediatrics and adults, primarily due to comorbidities and polypharmacy.

Drug - food interactions

Furthermore, an overwhelming majority of participants (92%, n=184) acknowledged that drug interactions could extend beyond concomitant drugs, encompassing food, vitamins/supplements, and alcohol. It was observed that physicians encountered challenges in determining the pharmacokinetic levels at which drugs, food, or beverages interfere with the target drug. However, a notable percentage (65%, n=130) of respondents successfully accomplished this task.

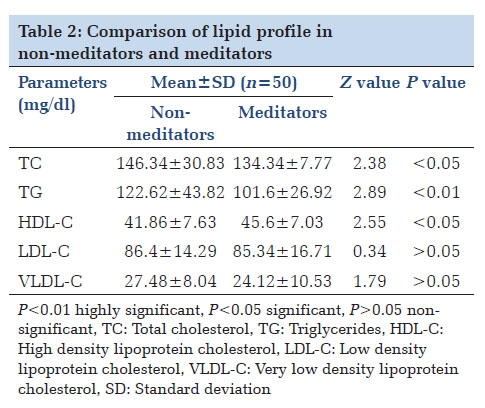

Moreover, the study revealed that a significant proportion of practitioners (78%, n=156) rely on monograms for dose adjustments when confronted with patients exhibiting renal or liver dysfunction. Additionally, a considerable majority (81%, n=162) of the respondents expressed the belief that certain drug interactions could occur if drugs were mixed before administration. This comprehensive insight into practitioners' knowledge underscores the complexity and multifaceted nature of understanding and managing drug interactions in clinical settings (Table 2).

|

Knowledge parameters |

Correct answer (%) |

Incorrect answer (%) |

No answer (%) |

|

Drug-drug interactions |

|||

|

Penicillin G with Gentamycin |

78 |

22 |

00 |

|

Thiopentone Na with Sch or morphine |

46 |

42 |

12 |

|

Heparin with hydrocortisone |

64 |

30 |

6 |

|

Noradrenaline with Na bicarbonate |

57 |

24 |

19 |

|

Drug-food interactions |

|||

|

Milk with Tetracyclines |

84 |

14 |

4 |

|

Theophylline with caffeinated drinks |

62 |

16 |

22 |

|

Iron supplements with citrus fruits |

78 |

14 |

08 |

|

Warfarin with food containing vitamin k |

86 |

10 |

04 |

|

Digoxin with oatmeals |

44 |

32 |

24 |

|

MAO-Inhibitors with tyramine |

39 |

38 |

23 |

|

Alcohol Interactions with |

|||

|

Metronidazole |

77 |

18 |

05 |

|

Methotrexate |

74 |

24 |

02 |

|

Benzodiazepines |

62 |

28 |

10 |

Awareness regarding reporting of drug interactions

Practitioners lack awareness regarding the reporting of drug interactions. Among 184 respondents, 92% recognized the necessity of reporting such interactions. Notably, 72% advocated for reporting within pharmacovigilance, while a mere 10% preferred FDA Form 3500, and an additional 10% suggested alternative reporting methods.

This underscores a prevalent knowledge gap among practitioners regarding the preferred modalities for reporting drug interactions, emphasizing the need for targeted educational interventions within the healthcare community.

Attitude towards drug interactions

In the attitude assessment, 79% of 158 doctors recognized a significant link between drug interactions and communication lapses with patients. Surprisingly, only 20% routinely informed patients about potential drug interactions, highlighting a substantial deficit in patient-physician communication as a primary contributor to such incidents.

Additionally, insights into prescribing practices revealed that 48% of practitioners (n=96) occasionally adjusted initial prescriptions based on drug interaction information. This adaptive behavior underscores the dynamic nature of clinical decision-making, emphasizing the ongoing requirement for heightened awareness and education within the medical community regarding drug interactions (Figure 1).

Q1: How often is the drug interactions information new to you?

Q2: Is the drug interaction information sufficient for you to manage the interaction?

Q3: How often do drug interactions information change your initial prescribing decisions?

Q4: How often does the risk for a drug interaction affect your selection of a drug product?

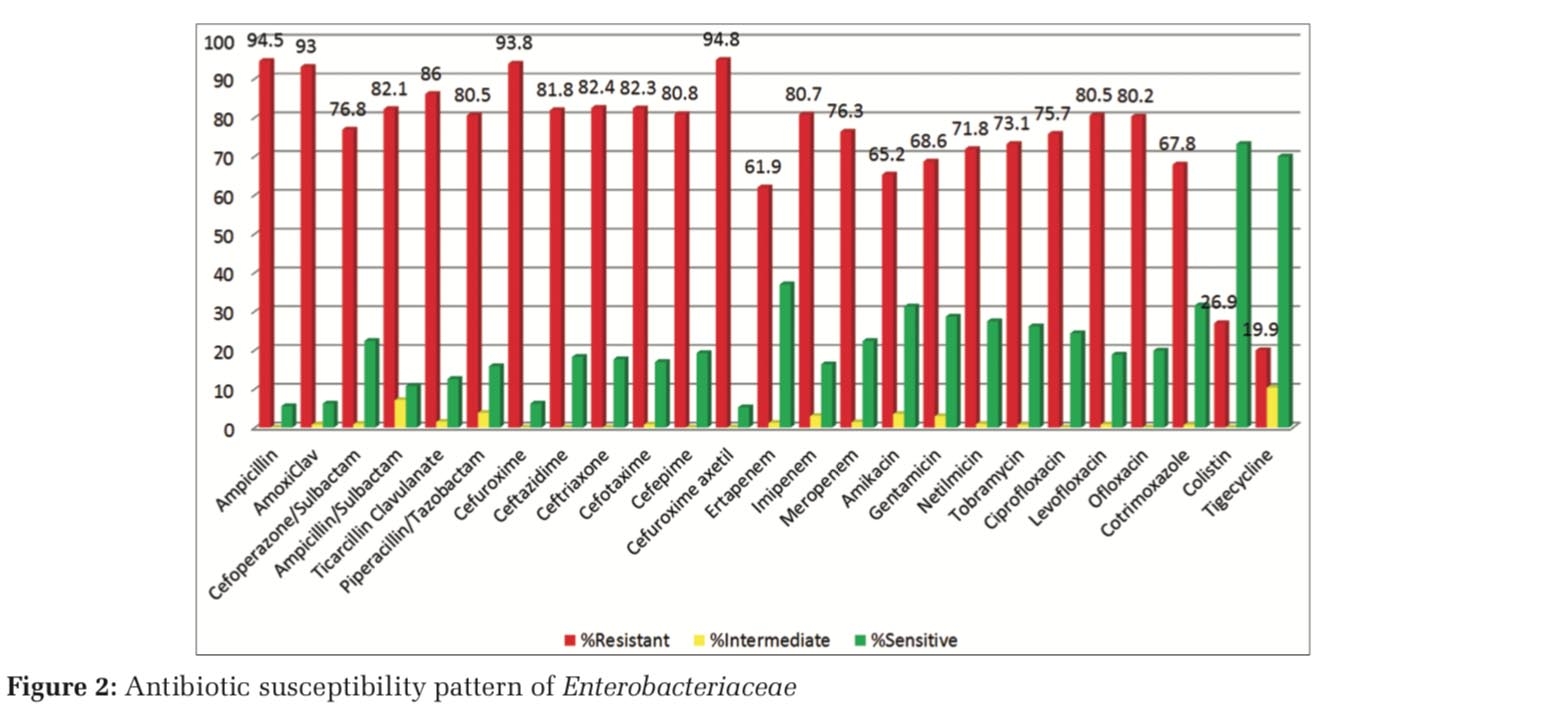

As polypharmacy is common due to multiple comorbidities with increasing age, practitioners should have keen insight about the concomitant drugs patient is taking by themselves or from other practitioners. In this study we found (n=156, 78%) of respondents have habit to ask each patient about consumption of concomitant drugs (Herbals/Traditionals) or Supplements for different conditions, out of which (n=134, 67%) respondents adjust the dose of the given drug according to the concomitant drug which causes DIs to happen. Among doctors, the practice of asking about OTC (over the counter) drugs as well as the patients buying them from pharmacists without prescription is less common, i.e., only 12% respondents ask about OTC drugs which results in significant increase in number of drug-drug interaction adverse reactions. While giving drugs, it is utmost necessary to know about feeding habits of the patient as food can alter the therapeutic potential of various drugs. In this study we found (n=170, 85%) of respondents tell each patient about prescribed medicines and the kind of food not to be taken together while (n=156, 78%) practitioners have in their practice to tell each patient whether medicines are to be taken before/after/after how many hours of taking food to avoid drug interactions. When more information was needed about a DDI, the respondents most commonly use Internet as their reference to learn about drug interactions as shown in Figure 2.

Doctors have different views on how they can avoid drug interactions. (n=4, 2%) respondents believe to do so by updating self knowledge, (n=12, 6%) respondents were aware about giving counseling to the patients and follow this method to avoid drug interactions. Few of the practitioners (n=16, 8%), avoid interactions by monitoring dose and dosage regimen, 1/10 of the respondents i.e., 10% believe in avoiding prescribing multiple drugs and have a strong view on ‘one pill for many ill’ whereas majority i.e., (n=148, 74%) had an opinion by doing all the above mentioned techniques to avoid drug interactions.

For the open-ended question about the various ways to improve awareness regarding drug-drug interactions suggested by the participants were:

-

Conducting educational workshops by pharmacologists on drug interactions.

-

Applying advertise-ments or banners in the outpatient Departments (OPDs).

-

Organizing regular interactive/knowledge sessions with clinicians.

-

Group discussion between pharmacologists and clinicians on how to prevent drug interactions.

-

Circulating important DDI for commonly prescribed drugs in OPDs.

-

Creating a software in which pharmacologist guides clinicians about DDIs.

-

Making DDIs reporting easier and accessible.

-

To appoint a pharmacologist in OPD besides dispensing to counsel patients about DDIs.

Discussion

Previous studies have reported gaps in the knowledge of physicians about the DIs. 15, 16 With through literature search there are few studies in India which shows knowledge and practice of practitioners about DIs. This study proves successful in evaluating the factors affecting DIs with the help of knowledge, attitude and practice among practitioners and plan a proper management strategy in developing new methods to reduce DIs. Most of the respondents believe that there is huge gap between communication of doctors and patient which results in significant drug interaction adverse reactions. A possible explanation for this might be very less doctor/patient ratio in Indian population, huge burden of patients in OPD and less doctor-patient communication time.

This study showed that the level of practitioner’s knowledge on DI is insufficient and found comparable with the finding of other studies. 17, 18 There are few differences between these studies. Unlike our study, in the study of Glassman et al. 17 the clinicians were allowed to use information sources when answering the knowledge test whereas in our study observer is present when practitioners filled out the questionnaire, they did not use any reference to answer the questionnaire. The drug pairs evaluated in our study had been already considered clinically important by experts but were different than in the study of Glassman et al. 17 and in the study of Ko et al. 18 which is responsible for difference in the findings of various studies.

This study findings on practitioners showed that they pay less attention to ask patients about the use of over the counter (OTC) products and other concomitant drugs which shows similarity with the findings of Ko et al.’s study. 17 A probable explanation for this might be that prescribers pay attention to the risk of interaction between drugs and OTC products less than the interaction between two prescribed drugs whereas most of the respondents have insight that patients came to tertiary center might not consume OTC drugs.

This study findings found comparable for attitude of practitioners towards drug interaction information to alter their prescriptions accordingly as found with the study done in Iran. 2 The minor differences in findings might be due to the fact that Iranian study include electronic sources and printed materials for their study as the source of information.

In this study most of the respondents use Internet as their reference source to learn more about an interaction rather than package inserts and journals, explanation of this finding is on the basis that most of the participants of the study are young generation of residents who are more comfortable with internet and social media promotions rather than written or printed materials.

Our study gives new management options and newer ideas for spreading awareness about drug interactions among clinicians. With the open-ended question many practitioners have a view that some interactive/communication sessions or lectures should be there at regular intervals in which pharmacologists give their expert advice for particular drug-drug or drug-food interactions. Some clinicians also in favour or applying banners and circulation of important DI for commonly prescribed drugs in the outpatient department. The implementation of an electronic surveillance system provides practitioners with the appropriate information to assess the degree of risk to the patient and to prevent potentially harmful DIs beyond what can be achieved with manual review, alone seems to be an effective action. But in it is difficult as almost all the prescriptions are handwritten. Monitoring systems are need of the hour because due to the lack of DIs monitoring systems, inappropriate prescription of drugs with potential DIs causing serious risks to patients’ health has not been studied extensively leading to decrease quality of patient care.

Strengths and Limitations

Drug interactions are among the most preventable adverse events and have significant negative impacts on patients’ safety. Therefore, enhancing knowledge and awareness of these interactions among doctors is crucial. The heterogeneity of the study includes practitioners of all the fields among the hospital setting.

The findings have limited generalizability and may not reflect the general doctor population in terms of their level of knowledge about DDIs. Smaller sample size is also one of the limitations of this study. Multicenter study with larger samples will be beneficial. Regional specificity of food, culture and even the individual specificity need to be considered. Therefore, additional training and integration of knowledge and expertise about DDI among healthcare professionals is needed to improve the therapeutic efficacy, patient’s drug compliance and patient’s safety.

Conclusion

The identification and prevention of potentially dangerous DIs is an important component of clinician’s life, and their role should be shifted from focusing on drug targeted approach to the patient-oriented approach. Physicians especially psychiatrists, cardiologists, neurologists, primary care physicians and general practitioners must remain vigilant in their monitoring of possible DIs and make appropriate dosage or adjustments to treatment. Although health care professionals surveyed in this study appear to have shown some expertise in their field of expertise, they have shown limited knowledge in others. Therefore, further training and integration of knowledge and expertise about drug-drug, drug-food interactions among health care professionals with pharmacologists at frequent intervals are essential to provide appropriate patient counseling and better treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. M.C Gupta (Head, Department of Pharmacology, PGIMS, Rohtak) for his valuable suggestions in framing the study design. The authors would like to thank all the practitioners for giving their valuable time to participate in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.