Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2019.v05i01.006

Year: 2019, Volume: 5, Issue: 1, Pages: 27-35

Original Article

Suhas Chandran1, M Kishor2, Supriya Mathur2, B N Madhusudhan2, N Kavya2, T S Sathyanarayana Rao2

1Junior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, JSS Medical College and Hospital, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore,Karnataka, India,

2Department of Psychiatry, JSS Medical College and Hospital, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. M Kishor, Department of Psychiatry, JSS Medical College and Hospital, JSS Academy of Higher Education and Research, Mysore, Karnataka - 570 004, India. Phone: +91-9686712210. E-mail: [email protected]

Background: India has one of the largest health-care systems in the world, and caregivers play an important role in assisting the patients in seeking services, supporting the patient during treatment and also in recovery, as there is a culturally determined emphasis on kinship obligations, with families playing a prominent role in all decisions regarding treatment. The burden this places on the caregiver can undermine their physical, psychological, and functional health. There is a paucity of studies examining caregiver burden in relation to type caregivers (formal or informal) and type of wards (general or special). Our study aims to explore whether their burden and coping differ in relation to the type of ward services.

Aims: The aim of the study was (i) to compare the burden among caregivers of general ward patients with that of special ward patients and (ii) to study the satisfaction of hospital services by caregivers in general ward versus special wards.

Methods: Sixty caregivers each of general ward and special ward patients were assessed. The caregiver burden scale was utilized to appraise burden, and their coping was evaluated with the revised caregiver efficacy scale.

Results:Caregiver burden was more for special wards compared to general wards. Caregiver self-efficacy was more among the primary caregivers of general ward patients.

Conclusions:Caregiver burden and self-efficacy play an important role in satisfaction with the service quality of the health-care organization. Education about various aspects of caregiving and early identification of burden areas should be done to allow optimal management strategies tailored for the individual patient and caregiver.

KEY WORDS:Caregiver burden, caregiver self-efficacy, general ward, private ward, type of caregiver.

India has the second largest population in the world. To cater to the health care needs of a population of 1.25 billion, there are >200,000 hospitals.[1] India also has the largest number of teaching hospitals affiliated with >470 medical colleges, apart from other public and private hospitals that provide care to the large majority of this population.[2] Majority of health-care centers in India are private in nature, especially in urban regions. In all health-care centers, it is the caregivers who play an important role in assisting the patients in seeking services, supporting the patient during treatment and also in recovery. In these contexts, the caregiver burden is an entity that is often overlooked by clinicians.[3]

Caregiver burden has been defined as a multidimensional response to the negative appraisal and perceived stress resulting from taking care of an ill individual. It threatens the physical, psychological, emotional, and functional health of caregivers.[4] An important determinant of burden and efficacy of caregivers is the type of ward that the patients are admitted in. Patients who seek service in private hospitals have the option to choose differential services based on their needs ranging from general ward to air-conditioned deluxe wards also called as special wards or private wards. The expenses for basic in-hospital treatment are much less in government hospitals as compared to private hospitals, but these public hospitals also offer additional facilities such as deluxe or special wards to patients willing to pay extra for it. In urban India, there has been an exponential increase in special wards even though exact data are unavailable. These special wards offer advantages and comforts such as better privacy, extra bed for caregiver, television (TV), air conditioners, adequate spacing, improved nurse-patient ratios, and better control of environmental factors like noise, and also facilitate nurses’ as well as healthcare workers’ ability to do their jobs efficiently.[5] These advantages often encourage the family members to utilize such services. Caregivers are broadly grouped as formal and informal caregivers. The formal caregiver is a provider associated with a formal service system, either a paid worker or a volunteer and most of the time it is the former.[6] The pattern of caregiver needs in the Indian scenario is also quite unlike the pattern of needs reported in western countries. In the west, a greater amount of help and benefits are usually received from Government health-care services; therefore, despite the fact that economic, welfare or treatment needs are met, social needs may remain unmet.[7] In Indian culture, there is this natural preference of families to be involved in the care of their ill which is encapsulated by what has been referred to as the “cure versus care” dichotomy, where family members believe that it is the duty of professionals to cure their patient, while providing care is their responsibility. This is further driven by a culturally determined emphasis on kinship obligations, nonmedical explanatory models of illness and a tradition of families playing a prominent role in all decisions regarding treatment.[8] This allows for the emotional needs of the patient to be better met and can also decrease the caregiver burden. There is a paucity of studies to understand what type of caregivers are involved with general and special wards in the Indian scenario, and whether their burden and coping differs in relation to the type of ward services has not been adequately studied.

The aim of this study was to compare the burden in caregivers of special ward patients with that of general ward patients. To study the association of caregiver burden with factors such as age, gender, educational status, duration of caregiving, and the relationship of the caregiver to the patient as well as to observe the association between burden and overall satisfaction with hospital services.

This was a cross-sectional, comparative hospital- based study. The study sample comprised caregivers of inpatients admitted in a private tertiary care general hospital in Mysore. An approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee board before its initiation. 60 inpatients in special wards were matched with patients with near similar illnesses in respective general wards. The sampling was random with computer generated numbers that were tagged to bed numbers. The caregivers were categorized as Group 1 (G1) consisting of 60 caregivers of general ward patients and Group 2 (G2) constituted by 60 caregivers of special ward patients. For each patient, the primary caregiver was taken into consideration. The primary caregiver has been defined as those who are >18years of age and have complete responsibility for the care recipient, a recipient who cannot fully care for himself or herself.[9] In addition, the age, sex of the caregiver, and duration of caregiving were also noted. The samples included caregivers of patients suffering from all conditions such as medical, surgical, and psychiatric illnesses. The caregivers were subsequently assessed with the caregiver burden scale and the revised caregiver self-efficacy scale. These scales were applied as a self-administered questionnaire in English to those who could understand it, and to the remaining subjects, it was delivered by interview technique in which the interviewer translated the questionnaire into the appropriate vernacular language in which both the patient and the interviewer were well acquainted. The interviewers were a junior resident in psychiatry as well as an intern resident.

The caregiver burden scale consists of 22 questions to assess the burden experience. Each question had a 5-item response, and each response was given a score from 0 to 4. The composite score was then calculated, based on which the burden was graded as: Little or no burden (< 20), mild (21–40), moderate (41–60), and severe (>60). It has good internal consistency reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficiency of 0.92.[10]

The revised caregiver efficacy scale comprises 15 questions. The response to each question was scored from 0 to 100 where a 0% confidence implied that you cannot do the concerned caregiving task at all and a 100% confidence implied you are convinced you can do the task. Out of these 15 items, there was an array of 5 questions each for measuring self- efficacy domains including efficacy for obtaining respite, efficacy for responding to patient’s disruptive behavior and efficacy for controlling upsetting thoughts pertinent to caregiving. It should be noted that the presence of disruptive behavior here does not necessarily equate to psychiatric illness.[11]

The overall satisfaction of hospital services was also assessed using a 10 point Likert scale. Higher the score on this scale more was the dissatisfaction of the caregiver with that type of ward.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Caregivers aged >18years who were involved in caregiving of the patient for at least preceding 1month which included at least 5 continuous days in the hospital were included. Caregivers whose age was < 18 years, caregivers of physically handicapped patients/patients receiving palliative care were excluded. Each of the caregiver’s and patient’s included was explained about the study and informed consent was obtained from both. In the case of formal caregivers, consent was taken from the patient’s relative as well.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and t-test with the help of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences-version SPSS for windows version 15.0.

The two groups, general and special ward primary caregivers shared almost similar attributes in terms of age, gender, and duration of caregiving. Most primary caregivers were females (n = 36 and n = 42 in a special ward and general ward, respectively) and the age of the caregivers ranged from 19 years to 68 years with a mean age of 37 and 40 in the special ward and general ward caregivers, respectively. Although most caregivers were family members (informal caregivers) in both the groups, there were 25% formal caregivers in the special ward populations who were paid for their services by the patient or a relative. In comparison, there were no formal caregivers in the general ward population [Table 1].

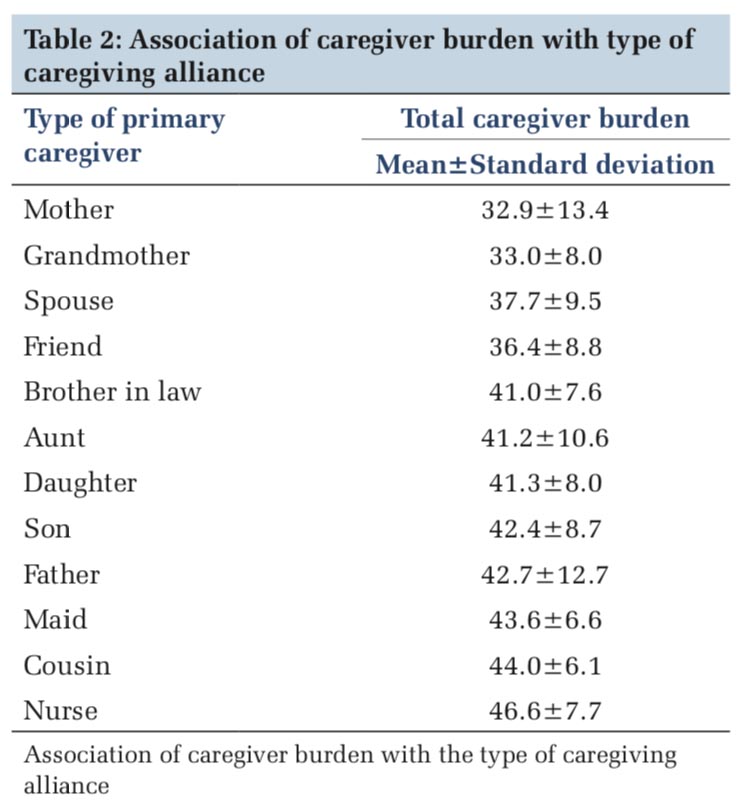

In our sample among the informal caregivers, the burden was most if the caregiver was a male particularly a son, followed by a daughter-in-law. The least burden was experienced by a spouse especially if it was a wife. Among the formal caregivers, the burden was most for a home maid [Table 2]. In the study, all the home maids were females. Appraisal of the Caregiver Burden Scale suggested that the mean total caregiver burden scores in the caregivers of special ward patients (μ = 45.4) were significantly higher in comparison to that of the general ward caregivers (μ = 35.4) (P < 0.01). The scores were also statistically significant in nine domains of caregiving burden [Table 3]. 70% of caregivers of special ward patients had moderate-severe burdens whereas 30% of caregivers of general ward patients had a similar severity grading. 58% of general ward caregivers had mild-moderate burden [Figure 1].

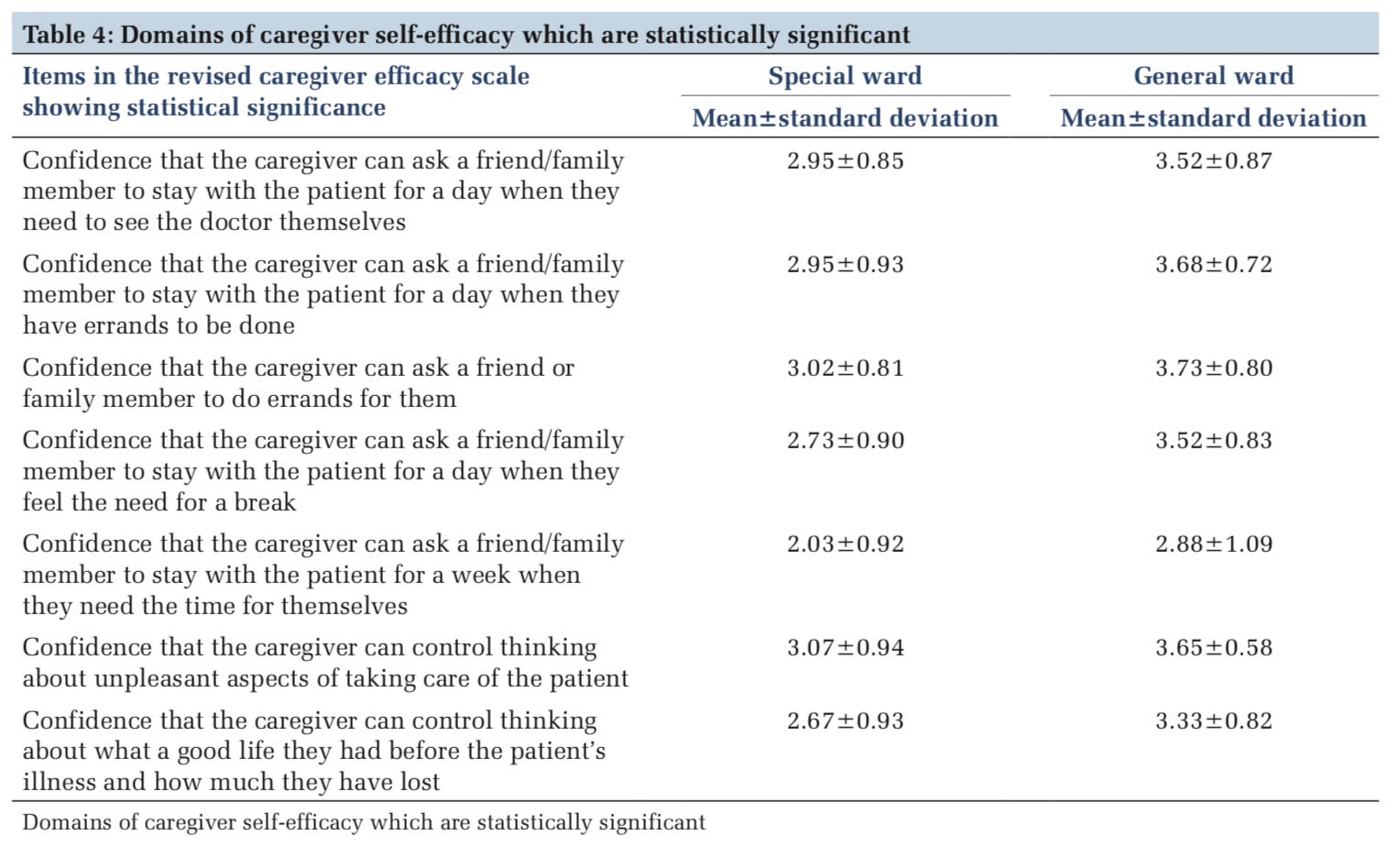

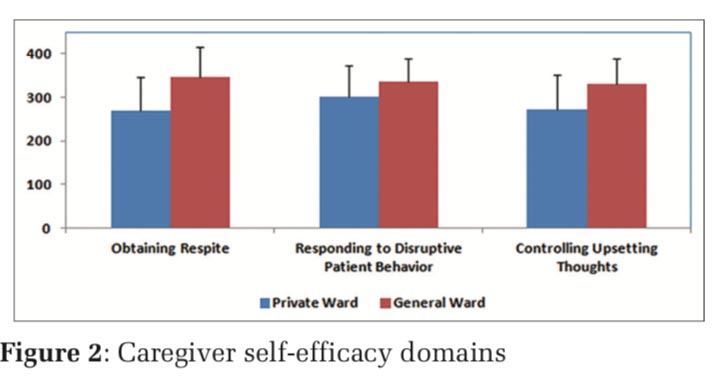

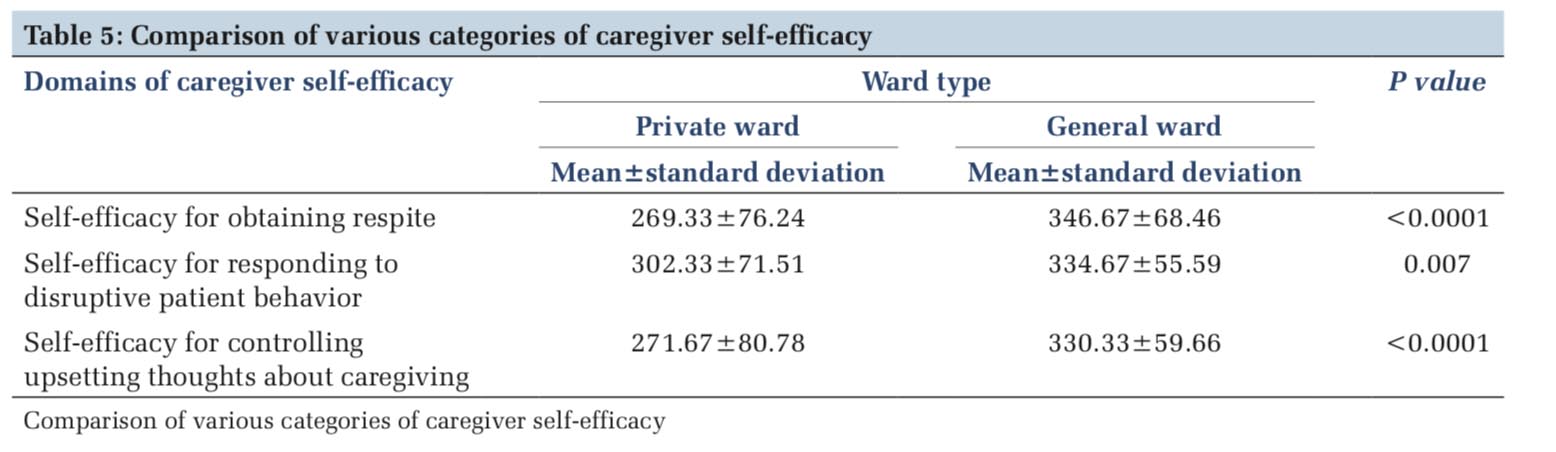

With the caregiver self-efficacy scale, the overall caregiver efficacy was more among the primary caregivers of general wards in comparison to special wards with statistical significance in seven domains of efficacy [Table 4]. The self-efficacy of general ward caregivers was observed to be better with P < 0.01 in domains of self-efficacy for obtaining respite and self-efficacy for controlling upsetting thoughts regarding patient care. The self-efficacy for responding to disruptive patient behavior was more in caregivers of general ward patients (μ = 334.6) in comparison to special ward patients (μ = 302.3), but this difference was, however, not statistically significant [Table5 and Figure2]. The caregiver burden was more among those who were involved in the care of patients with psychiatric illness (μ=49.6) and the least among those caregivers who were taking care of patients with pyrexia of unknown origin (μ = 33.3) [Table 6].

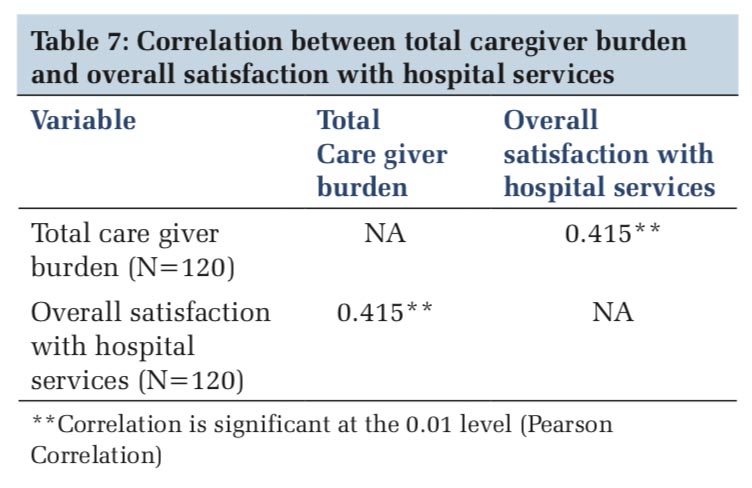

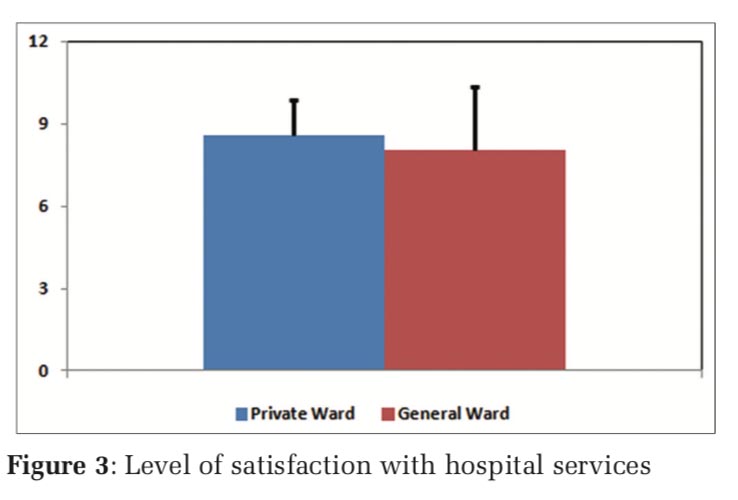

The overall level of satisfaction with hospital services was assessed with the help of the Likert scale. The caregivers of special ward patients reported greater dissatisfaction when compared to the general ward population [Figure 3]. Further on probing the strength of a relationship between overall levels of satisfaction with hospital services and total caregiver burden using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient established a significant positive linear correlation (R = 0.415, P < 0.01).

Our study shows that caregivers in both the groups were predominantly females which were in line with the findings of previous studies.[12-14] More recently in the west, it has been noted that the proportion of men providing care, notably for the elderly has been gradually increasing, so much so that men could complement nearly half of the primary caregivers of the geriatric population. In the Indian context, it seems natural for the female gender to provide care, but whether this trend will stay the same or subsequently decline remains to be seen.[15-17] Majority of the caregivers in both groups were < 40 years of age, which highlights the importance of involving the younger population in caregiving education models.[5] The study also demonstrated that the burden was higher among the caregivers of patients with psychiatric illness compared to other illnesses, which is consistent with other studies. Looking at the type of caregivers, 25% of the primary caregivers of the special ward population were formal caregivers who were paid-service providers in comparison to the 100% informal caregivers of general ward patients. It is a matter of concern that increasingly, caregivers in the special wards are more likely to be non-family members. The overall caregiver burden was more for special wards compared to general wards and caregiver self- efficacy was more in primary caregivers of general ward patients. Thus, burden and efficacy were not reflective of the perceived better availability of services in the special wards. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that looked at the influence of the type of ward and type of caregiver on caregiver burden.

Probable reasons for increase in burden among caregivers of special ward patients may be that they are more isolated and may get fewer opportunities to discuss with or observe other caregivers and hence have less experiential learning in comparison to the general ward caregivers, where many share the same ward which favors inter caregiver communication, discussion on illness, distress or other issues, which may help in sharing of burden, knowledge, and experiential learning. This could be significant in lowering the caregiver burden scores and increasing self-efficacy scores in the general ward.

The other possible reason could be unmet expectations in the special wards. Expectations, in the premise of health care, point to the anticipation or the belief around what is to be encountered in a consultation or the health-care system. Every caregiver who comes with a patient for a consultation has expectations based on his or her perception of the illness, cultural background, health expectations, and attitudes.[18] In special wards, caregivers may tend to have higher expectations regarding early response to distress and the amount of attention from the clinical staff that should be made available. Special wards or private wards, even though more expensive, are considered vastly superior in terms of comfort with the availability of accessories such as TV, air conditioners, and extra beds. Furthermore, improved infection control, heightened privacy, improved sleep due to lower levels of environmental disturbances, and fewer preventable medical errors contribute to reduced lengths of hospital stay.[19] However, at the same time, unrealistic expectations may be prevalent in caregivers of these special wards, which can increase caregiver burden and reduce their efficacy. Examples of unrealistic expectations may include: Wanting to discuss several problems with the treating team without time constraints, or access to services such as buying medications or lower nurse to patient ratio for hassle-free manner of services, as well as an immediate response to every concern raised. Reactions to such unmet expectations can vary from disappointment to anger, and this could potentially negatively influence caregiver burden and self-efficacy. Therefore, this study stresses on probing the expectations of caregivers, which can be beneficial in averting these reactions, enhancing their health-care experience, and reducing their burden.

There could be several methods to reduce this caregiver burden. One approach would be for the treating team to specifically focus on the expectations of the special ward caregivers. It is important to counsel the caregivers about the available resources right on admission, thereby abolishing any false expectations during the stay. Sometimes, the time constraints and having to tend to the requirements of multiple patients in different wards might make this job difficult for the primary doctors. In such instances use of a health care manager for every floor, or designated nursing staff for this purpose might help accomplish this task.[20] Alternatively, group discussions among all caregivers can be facilitated in special wards or with those of the general ward so that an atmosphere for experiential learning is created. Overall, an appropriate balance should be realized between patient expectations, physicians’ perceptions, and priorities set by health- care planners to prevent this escalation of burden.

The other important aspect of this study is about the caregiving alliance, which is different when the primary caregiver is an informal/family member as a caregiver, in comparison to a formal caregiver or paid caregiver which formed one-fourth of the study in the special ward group, who incidentally, also showed higher burden. In India, the family is the most significant foundation that has survived through the ages. Families embrace the role of primary caregivers for two reasons. First, it is due to the Indian custom of affiliation and concern for near and dear ones during adversities. As a result of which, most Indian families choose to be wilfully involved in all aspects of the care of their relatives even though it is time consuming.[21] Nowadays, there has been a change in the family composition in India, with an increase in the number of nuclear families. Nuclear families could resort to employing paid/formal caregivers due to an unavailability of informal caregivers.

It is important to know the driving factors for choosing paid/formal caregiver, which may be time constraints and vocational limitations of family members, but could also be due to other contributory factors. Family caregivers may feel unprepared to provide care or unease with patients’ behaviors such as yelling/screaming when in distress, they may believe they have insufficient knowledge to deliver competent care and receive limited guidance from the formal health-care providers.[22] The caregivers may be incognizant with the type of care they must provide or the amount of care needed and may not know how to access and best utilize the available resources. This might push family members to hire a formal caregiver to overcome these limitations. Education directed toward these barriers might increase their awareness regarding various aspects of caregiving which may, in turn, influence their decision-making on the choice of caregivers for a particular illness or patient.

Care recipient behavior such as screaming, yelling, swearing,andthreateningisoftenbettertolerated by an informal caregiver, especially a spouse or a parent.[23] Moreover, since formal caregivers are hired through private organizations, they are more likely to be changed often.[20] This is unlike informal caregivers, where the primary caregiver’s role is more constant. Hence, a close association and understanding between the patient and caregiver are paramount for improved health-care outcomes.

One of the most important determinants of the patients and caregivers’ choice of hospital is their levels of satisfaction with the service quality of the health-care organization. The study explored the overall satisfaction of the caregivers with hospital services in special wards compared to general wards and levels of satisfaction were found to be much more in the general ward compared to the private ward population, against the popular assumption. This difference could be attributed to the above- mentioned factors, suggesting that the higher caregiver burden in special wards has a negative impact on hospital satisfaction.

Limitations

The study had a small sample size and was limited to one hospital; hence, the results cannot be generalized. The study did not take into account determinants such as the education status of the caregivers, health status of the caregivers, household incomes, and average daily caregiving time, which may have had an association with the study parameters of caregiver burden and self-efficacy. Therefore, further studies are needed to evaluate all the factors influencing caregiver burden, caregiver self-efficacy and their overall levels of satisfaction with these differential ward services.

The burden on caregivers and the factors associated with it varies from special ward to the general ward. Education of the caregivers regarding various aspects of caring for the patient will help in improving caregiver efficacy. This also has an impact on satisfaction related to hospital services, which makes it imperative that early identification of these determinants should be done to help the treating team tailor the services that will allow optimal management strategies for caregiver burden and thus improve overall patient care services.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.