Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2017.v03i03.005

Year: 2017, Volume: 3, Issue: 3, Pages: 29-32

Case Report

Roma Jawane1, M Hemapriya2, Raja Parthiban3

1Post Graduate Resident, Department of Pathology, MVJ Medical College and Research Hospital, Dandupalya,Hoskote, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India, 2Post Graduate Resident, Department of Pathology, MVJ Medical College and Research Hospital, Dandupalya, Hoskote, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India, 3Professor and Head, Department of Pathology, MVJ Medical College and Research Hospital, Dandupalya, Hoskote, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. M Hemapriya, Department of Pathology, MVJ Medical College and Research Hospital, Dandupalya, Hoskote, Bengaluru - 562 114, Karnataka, India. Phone: +91-9535255133. E-mail: [email protected]

Dyschromatosis Universalis Heriditaria (DUH) is an autosomal dominant disorder that usually presents in infancy or early childhood in Asian families and is characterized by pinpoint to pea-sized hypo- and hyper- pigmented macules, distributed in a reticulated pattern over the trunk, abdomen, and limbs, usually sparing the face and palmoplantar surfaces. It was reported initially and mainly in Japan. However, subsequent cases have been reported from other countries. This report describes DUH in four members of the same family. Skin biopsies of representative lesions from all the affected family members were taken and processed for histopathological examination. The tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and also a special stain for melanocytes was performed to arrive at a diagnosis.

KEY WORDS:Dyschromatosis Universalis Heriditaria, genodermatosis, pigmented lesions, melanin pigment.

Dyschromatosis universalis heriditaria (DUH) was first reported in Toyama, Japan, in 1929.[1] Dyschromatosis is a group of disorders characterized by the presence of both hyper- and hypo-pigmented macules, which are small and irregular. These is a spectrum of disease which includes DUH, dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria (DSH)/ acropigmentation of Dohi, Dowling-Degos disease, and a segmental form known as unilateral dermatomal pigmentary dermatosis.[2] In the present study, four members of the same family presented with multiple hypo- and hyper-pigmented macules over both the upper and lower limbs and also over the trunk. The lesions started at infancy and gradually increased.

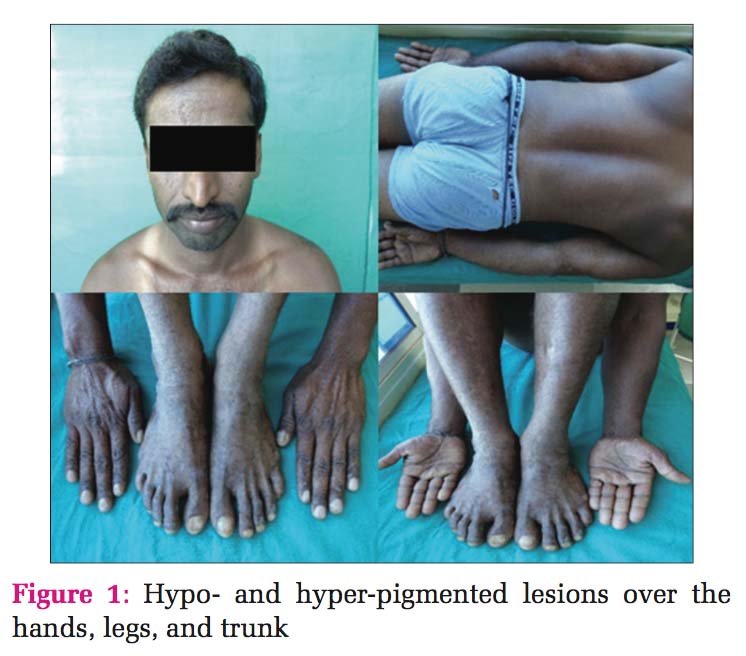

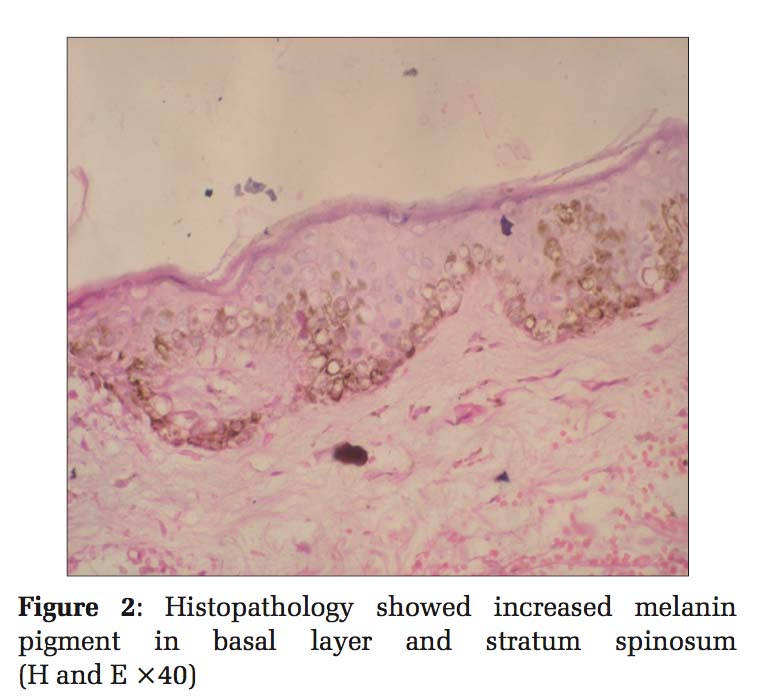

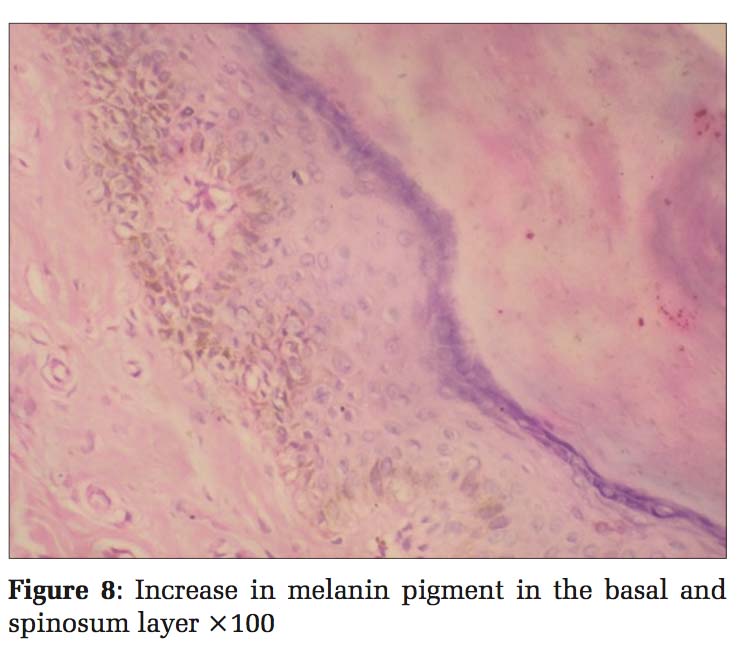

Case 1 Father, 39-year-old male, developed small lesions at the age of approximately 1 year. Initially, the lesions were raised and then ruptured to form hypopigmented to hyperpigmented lesions over both arms, legs, partly spread to involve trunk and palms. Face was spared. The was no history of photosensitivity. Histopathology of hyperpigmented lesions showed increased melanin pigment in the basal layer and stratum spinosum, whereas the biopsy from hypopigmented lesions showed a decrease in the melanin pigment in the basal layer [Figures 1 and 2].

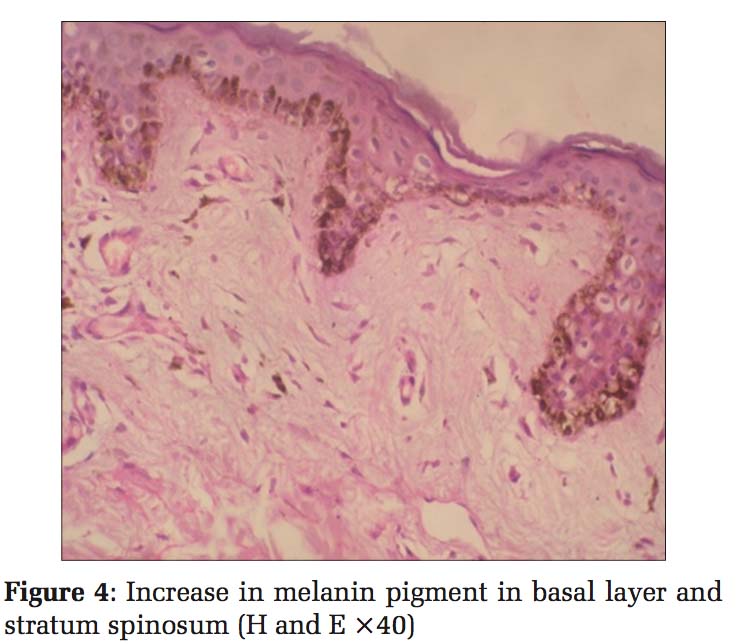

Case 2 Daughter, 11 years old [Figure 3], developed clinical history same as her father, hypo- and hyper- pigmented macules over the hands, legs, and trunk. Histopathology also showed the same findings with an increase in melanin pigment, and hence, a diagnosis of DUH was given [Figure 4].

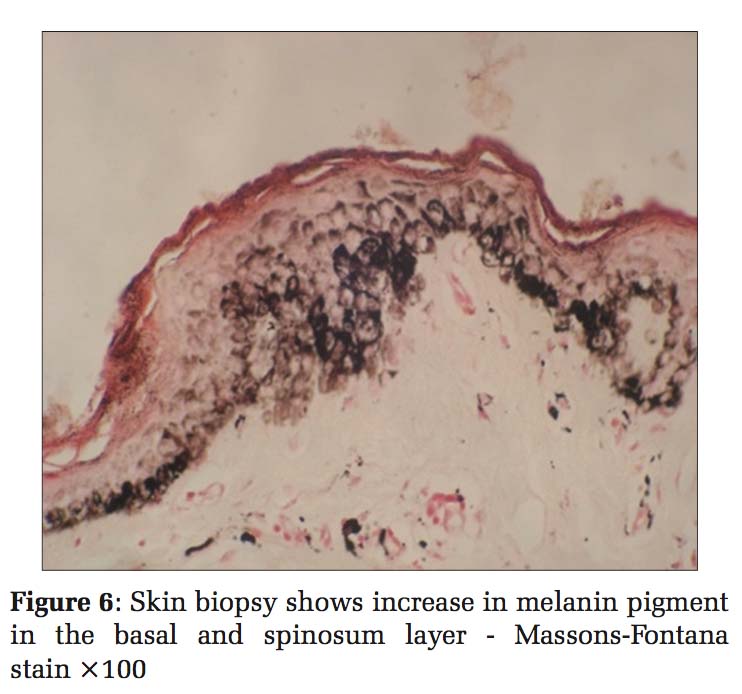

Case 3 Daughter, 8 years old [Figure 5], developed clinical history same as her father (case 1). Histopathology also showed the same findings, so the diagnosis was given as DUH [Figure 6].

Case 4 Daughter, 6 years old [Figure 7], developed clinical history same as her father (case 1). Histopathology also showed the same findings, so diagnosis was given as DUH [Figure 8].

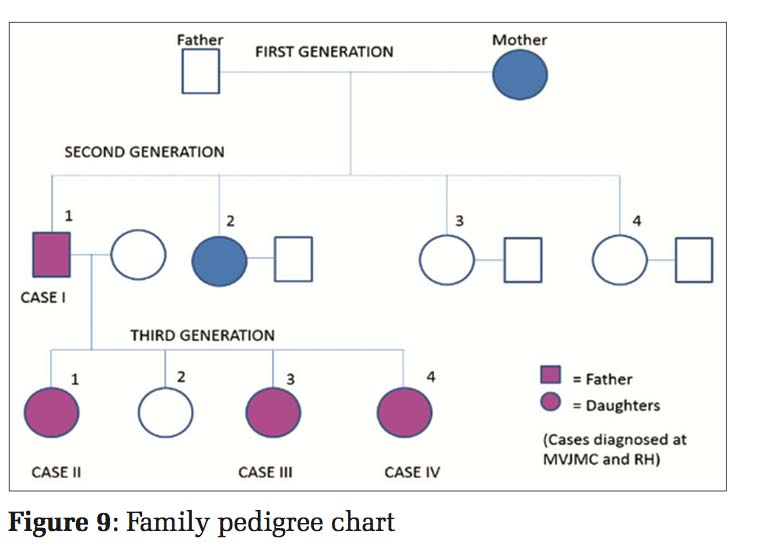

This case report describes DUH in four members of the same family: Father 36 years and three daughters 11 years, 9 years, and 6 years, respectively. All of them developed similar lesions at the age of approximately 1 year. Initially, the lesions started in the hands and legs and gradually spread to the trunk and palms. However, the face was spared from the lesions. The lesions appeared as small macules which were slightly raised, and then, they ruptured to form hypopigmented to hyperpigmented lesions. There was no history of any contact with chemicals or any history of significant drug intake or photosensitivity. It was a non-consanguineous marriage among the parents [Figure 9].

On examination, multiple hyper- and hypo- pigmented macules are noted in the trunk, arms, forearms, hands, thigh, legs, and soles. Face and mucous membrane were spared. Systemic examination did not reveal anything significant.

Biopsies were taken from both the hyper- and hypo-pigmented areas from all the family members and sent for histopathological examination. The tissue was fixed in 10% formalin and processed routinely. Sections of 4 μ were taken and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and also with Masson- Fontana stain and studied under light microscope.

Histopathological examination of skin biopsies from the hyperpigmented lesions of all the four cases showed epidermis with mild atrophy and hyperkeratosis. The basal layer showed vacuolar degeneration with an increase in the melanin pigment, and at focal areas, melanin pigments were seen in stratum spinosum. Upper dermis was mildly edematous with multiple dilated small blood vessels, sparse lymphocytes, and melanophages. Sections stained with Masson-Fontana showed marked increase in melanin pigments migrating upward into stratum spinosum. Biopsies from the hypopigmented lesions showed a decrease in the melanin pigment in the basal layer. Histopathology diagnosis was given as DUH for all the four cases.

This is an autosomal dominant disorder, but a few cases have shown a recessive pattern.[2] It comprises hyper- and hypo-pigmented macules on the dorsal extremities and the face in a reticulate pattern with onset in infancy or childhood.[3,4] It occurs worldwide but is mostly described in Japanese families. In 1933, Ichikawa and Hiraga first described DUH.[5]

In contrast with DSH, hyper- and hypo-pigmented macules arise mainly on the trunk, and the onset is usually earlier, in the first year of life. Previously, it has been suggested that DUH is a disorder of melanocyte number. According to a recent electron microscopic study, it has been suggested that DUH may not be a disorder of melanocyte number but rather a disorder of melanosome production in epidermal melanin units.[6]

Although the exact etiology of this disorder is unknown, light and electron microscopy demonstrates differences in fully melanized melanosomes in affected areas of skin rather than altered melanocyte number. However, unlike DSH, DUH is not associated with mutations in the gene ADAR1, and therefore, it is considered as two different entities.[7-9] The lesions of DUH do not show any progression or regression with age.[10]

In our report, a history of similar lesions in father and his three daughters was noted. The lesions were gradually increasing without any regression with age. Systemic abnormalities reported in isolated cases include short stature, deafness, erythrocyte, platelet and tryptophan metabolism abnormalities, cataract, and grandmal seizures were conspicuous by their absence.[5] The differential diagnosis for DUH is vitiligo, dyskeratosis congenita, residual leukoderma dyschromic amyloidosis, and diphenylcyclopropenone exposure to chemicals such as monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone. Clinically, the lesions of DSH have to be differentiated from xeroderma pigmentosum as both the disorders of the patients show lesions in the photo-exposed areas. However, in our case report, the lesions were present in the unexposed sites such as trunk as well. Furthermore, the lesions did not show any atrophy or telangiectasia which is commonly seen in xeroderma pigmentosum. All the affected family members had no history of contact with chemicals or any significant drug intake.

DUH is a rare disorder showing autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. Recent studies have shown evidence of genetic etiology. Only genetic counselling is advised as there is no treatment modality available. DUH occurring in four members of the same family is reported because of its rarity. Although it is a rare disorder, it must be distinguished from xeroderma pigmentosum and other dyschromias.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.