Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2021.v07i01.008

Year: 2021, Volume: 7, Issue: 1, Pages: 43-51

Original Article

J. Shivanand Manohar1, Raj Kiran Donthu2, K. R. Syam3, M. Kishor1, Keshava Pai4

1Department of Psychiatry, JSS Medical College, Mysore, Karnataka, India,

2Department of Psychiatry, Konaseema Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Foundation, Amalapuram, Andhra Pradesh, India,

3Department of Psychology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka, India,

4Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Raj Kiran Donthu, Department of Psychiatry, Konaseema Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Foundation, Amalapuram, EG Andhra Pradesh, India. Phone: +91-9642859279. E-mail: [email protected]

Background: Medical postgraduates are exposed to more time in patient care and thereby higher stress. Personality is one of the important factors associated with stress. Studies exist in profiling personality traits and also assessing stress in medical professionals. However, in India, to the best of our knowledge, there are only few studies linking personality traits with stress in different branches of medicine.

Aim : The aim of the study was to study the association between big five personality traits and stress among medical postgraduates.

Setting and Design This was a cross-sectional study in medical college.

Materials and MethodsBig five inventory, perceived stress scale 14.

Statistical Analysis Used Chi-square, t-test, analysis of variance, correlation.

Results Personality pattern among postgraduates were low on openness (P = 0.000), neuroticism (P = 0.001), and high agreeableness (P = 0.007) compared to general population. Among the different branches pre-paraclinical branches have low openness (P = 0.004), medical branches have high agreeableness (P = 0.000), low openness (P = 0.000), surgical branches have low openness (P = 0.004), and neuroticism (P = 0.003). Married students have high neuroticism (P = 0.007). Perceived stress is high in all variables compared to general population. Among different subjects of medical sciences, it is significantly high in pre-paraclinical (P = 0.001) and clinical branches (P = 0.001). Negative correlation exists between conscientiousness (r = −0.233, P = 0.025), extraversion (r = −0.204, P = 0.050), and positive correlation between neuroticism (r = +0.607, P = 0.000) with perceived stress.

Conclusions:Medical postgraduates have low openness, neuroticism, and high agreeableness. Perceived stress is high in medical postgraduates in all demographic variables compared to the general population.

KEY WORDS: Personality, psychological stress, medical students.

Personality is a distinctive and characteristic pattern of thought, emotion, and behavior that makes up an individual’s style of interfacing with the surroundings.[1] Various views and theories of understanding personality exist; some of these are biological, cognitive, humanistic, learning, psychodynamic, etc., type and trait theories study people’s characteristics and their organization into systems. Traits are described as relatively stable over time but differ across individuals. Gordon Allport was a pioneer for studies on personality traits. He classified traits into “Cardinal,” “Central,” and “Secondary.”[2] Later, a variety of theories and scales were developed for understanding and assessment of personality. Among the methods of assessing personality, there was no consensus or clarity. After many years of research; the personality field has arrived at a consensus on the taxonomy of personality traits, the big five personality dimension. This was developed by Robert McCrae and Paul Costa and is believed by many as sufficient and has five traits; openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.[3,4]

According to Goldberg, the big five does not represent the intrinsic quality but it emphasizes that each of these factors is extremely broad.[3] Openness trait is commonly associated with imagination, being well-cultured, curious, broad-mindedness, intelligent, and artistic. Conscientiousness trait reflects thoroughness at things, being responsible, organized, hard-working, achievement-oriented, and persevering. Extraversion trait includes being sociable, assertive, talkative, and active. Agreeableness trait means being courteous, flexible, trustworthy, cooperative, soft-hearted, and tolerant. Neuroticism trait includes qualities such as anxious, angry, embarrassed, emotional, worried, and insecure.[5] Personality traits of an individual play an important role in the way an individual interacts with his/her environment. They also influence the way individuals select both social and non-social environments (college classes, job, place to live, relationship partners, etc.) and how much they modify those environments.[3]

Stress refers to the experience of events that are perceived as endangering one’s physical or psychological well-being. These events need real changes or readjustments in the normal self, it may be on the positive or negative aspect.[6] Personal factors (such as individual traits) and environmental factors (such as aspects of the job or a relationship partner) interact to produce behavioral and experiential outcomes. Stress can be of two types; objective and subjective. Objective measure implies that events are the cause of pathology and illness behavior. On the other hand, subjective measure implies that event is cognitively mediated; emotional response to the objective event and not the objective event itself. Hence, the response to the stress is not based on the intensity or inherent quality of the event, rather depends on the personal and contextual factors.[7]

Personality traits have been implicated in persons’ life experiences. It was proved that those with high neuroticism experience more negative emotions like anxiety. Similarly, positive emotions have been associated with cheerfulness and optimism. In the studies, those with higher neuroticism in addition to experiencing negative emotions, also produce stressful situations and show cognitive vulnerabilities leading to higher levels of perceived stress.[8]

Medical professionals were exposed to extended work hours and studies have shown that they suffer from a considerable amount of stress.[9] The previous studies linking stress with particular personality traits among medical professionals have shown mixed results and the majority of these studies were done on the non-Indian population. As per our knowledge, the study is scarce in India, and that too looking among the different branches of medical postgraduates. We felt that postgraduation is an important phase in a future specialist where the amount of stress is more and personality traits play a significant role in coping. Hence, there is a gap in our understanding of postgraduate personality and stress. This study tries to look at the link between different personalities traits and stress among different medical branches.

Aim of the study

Institutional Ethics Committee

The study is examined and approved by the Institutional ethics committee. The study was started after getting approval.

Questionnaires used

Socio-demographic sheet – To note down the demographic details of the participants.

Big five inventory (BFI) – [3] This is a 44 item self- rated scale. Each item is a short question and rated on a Likert scale where responses were rated from one to five, ranging from “Disagree strongly” to “Agree strongly.” Some of the questions are reverse scored. Questions were grouped into big five personality traits; which are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. The score values for questions were grouped to get a mean score for each trait. The mean value for each trait is used for the analysis. The scale is available in the public domain freely for research purposes after submitting a short survey regarding the purpose of use from the author’s website. The author has provided comparison sample values as per age for comparison with the study.

Perceived stress scale 14 (PSS 14) –[7,10] This is a measure of the degree to which situations in one’s life were appraised as stressful. Items were designed to tap how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives. It can be used in the community with the education of at least middle school. There are three different versions of this scale; we have used the 14 item version. Each item is rated on a Likert scale, where responses are given from zero to four, ranging from “Never” to “Very often.” The values of the questions were averaged to get a mean score, which is used in the study for analysis. The scale is available free from the author’s website. The author has provided comparison sample values for various demographic details for comparison with the study sample.

Study details It was a cross-sectional study conducted on postgraduate students of various branches studying in a private medical college who provided informed consent. The study was conducted between August 2014 and October 2014. Participants were assured of confidentiality. A total of 110 students participated in the study, out of the 17 were excluded due to missing data. The final sample included 93 participants. We did not include psychiatry postgraduates as we were involved in the sample collection and felt that it could lead to bias in the study. As perceived stress is dependent on many variables which can act as confounding factors; we tried to control the most evident factors. Hence, the study was conducted when the participants did not have any internal/ semester exams nearby.

Statistical analysis The data collected using study forms were entered into a Microsoft Excel sheet. The data were analyzed using a Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 18 (IBM corporation, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Data were subjected to analysis based on the study aims and objectives to obtain mean, percentages, standard deviation, Chi-square test, independent student t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and correlation where applicable taking P < 0.05 as significant and 95% confidence intervals. The data obtained were then tabulated and discussed in the study.

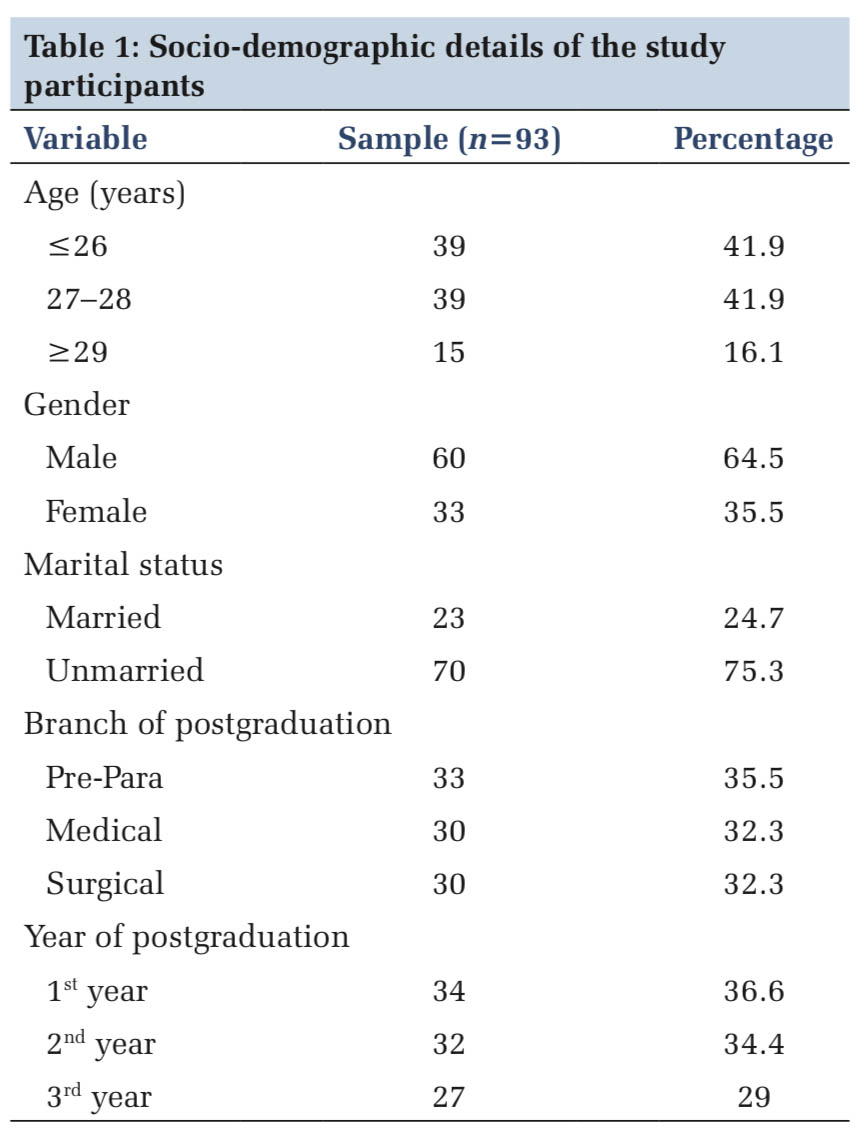

Socio-demographic variables [Table 1] The study included 93 postgraduate students of age ranging from 24 to 31 years. About 62% of the sample belongs to the age between 26 and 28 years. Male students constitute around two-thirds of the sample. About 70% of the sample is unmarried. The study has postgraduate students from almost all the branches; they are grouped into three for the simplicity of discussion. Pre-paraclinical branches include anatomy, biochemistry, physiology, microbiology, pathology, forensic medicine, pharmacology, and community medicine; Medical branches include general medicine, radiology, anesthesia, dermatology, pediatrics, and pulmonary medicine; and surgical branches includes general surgery, orthopedics, otolaryngology, ophthalmology and obstetrics, and gynecology. The study has approximately one-third of the sample in each group. Approximately 36% of the participants were in their 1st year of postgraduation.

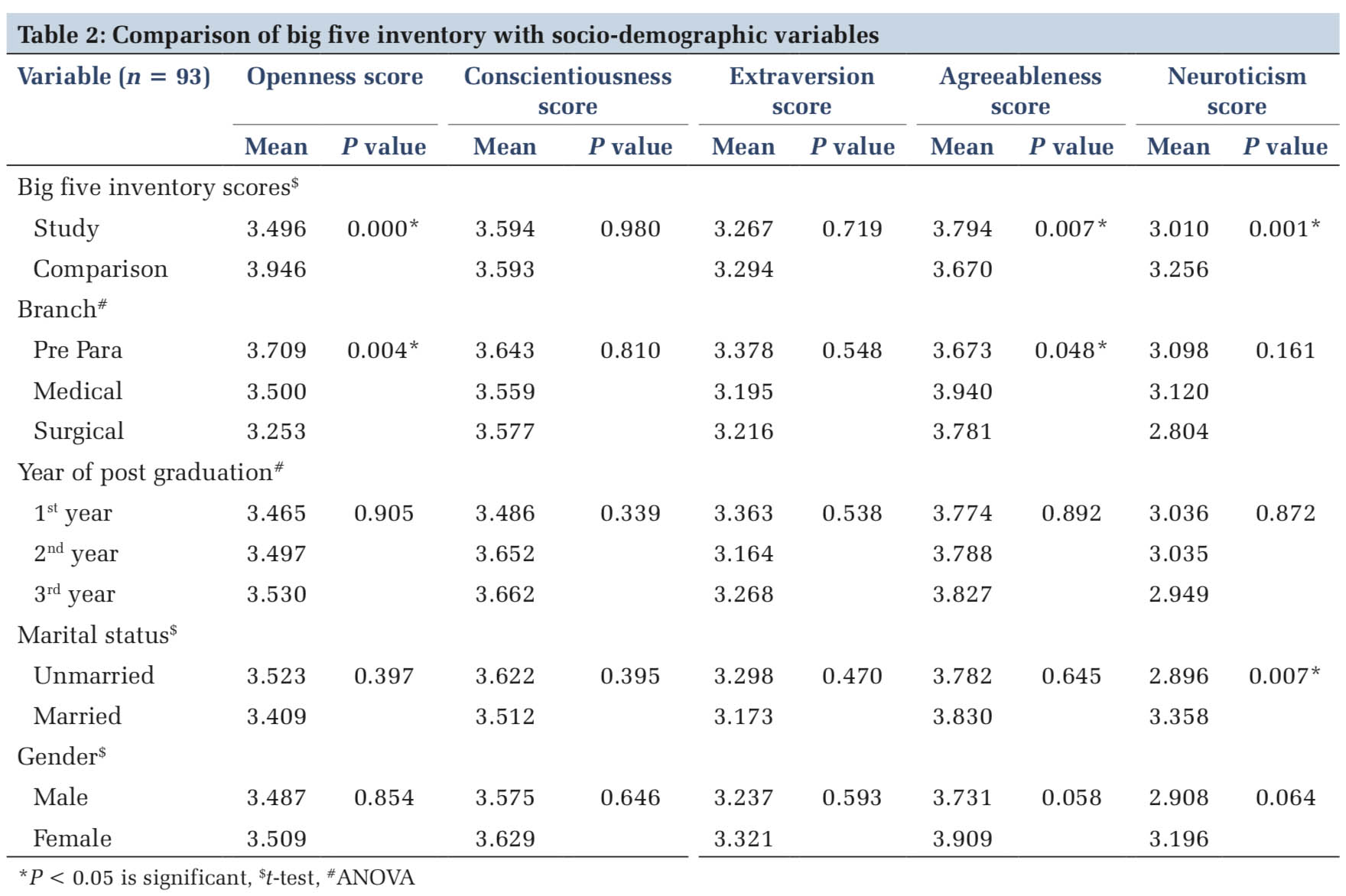

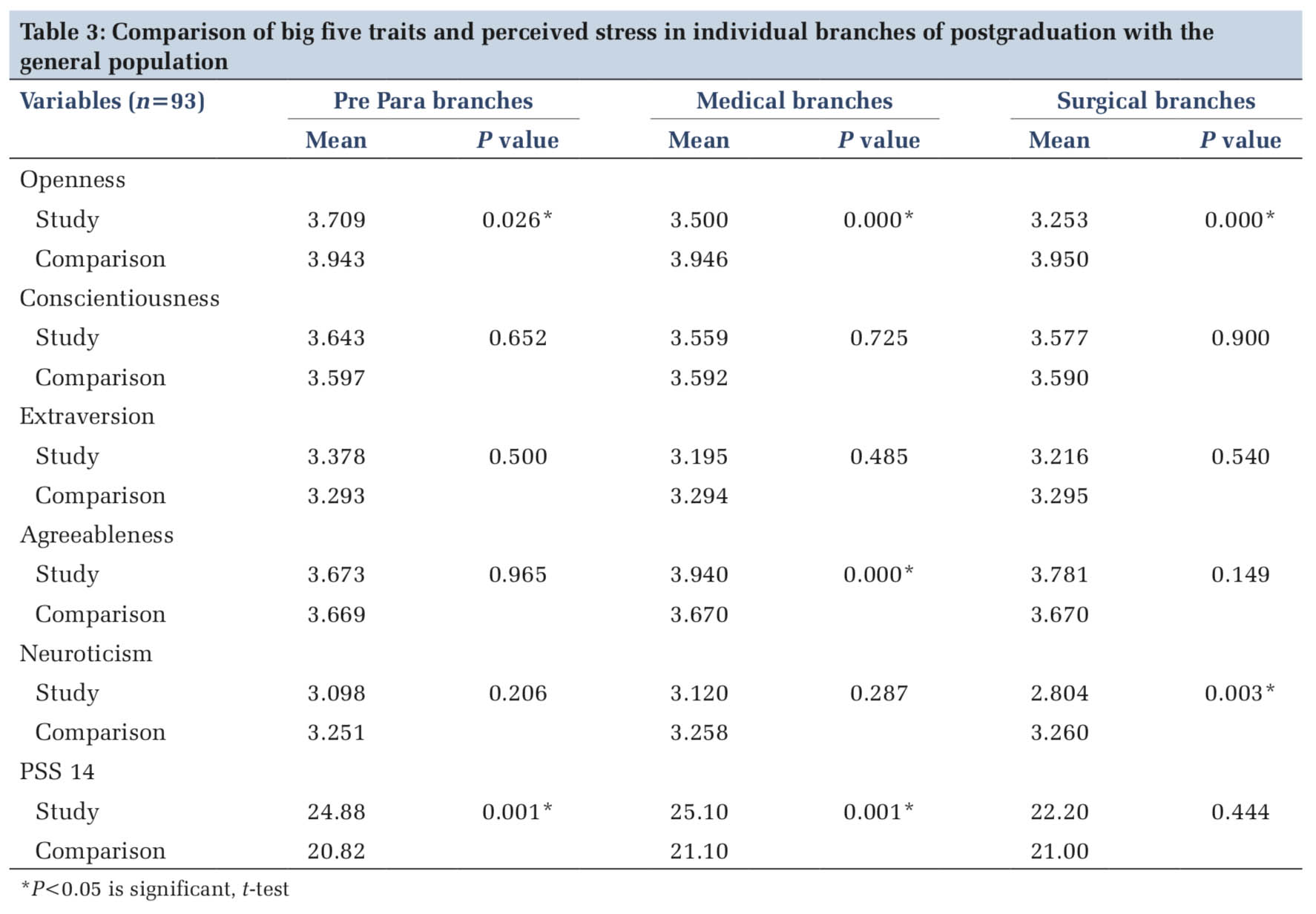

BFI [Tables 2 and 3] Participants’ mean values for each one of the big five personality traits are compared with the comparison sample given by the authors, which are adjusted for age. Using the Student’s t-test, there is a significant difference between the participants and the comparison sample in the following personality traits; openness, agreeableness, and neuroticism. The participants scores low for openness (P = 0.000); neuroticism (P = 0.001); and scores high for agreeableness (P = 0.007) personality traits. In between the different branches using ANOVA, there is a significant difference in openness (P = 0.004) and agreeableness (P = 0.048); surgical branches score low for openness, and medical branches scores high for agreeableness. When each branch is, in turn, compared with the comparison sample separately using the Student’s t-test, there is a significant difference in the following personality traits – pre para branches scores low for openness (P = 0.026); medical branches scores low for openness (P = 0.000); and high for agreeableness (P = 0.000); whereas surgical branches scores low for openness (P = 0.000) and neuroticism (P = 0.003). Married participants show a significant score in neuroticism (P = 0.007) trait when compared to unmarried students. There is no significant difference between the years of postgraduation and among the gender of participants.

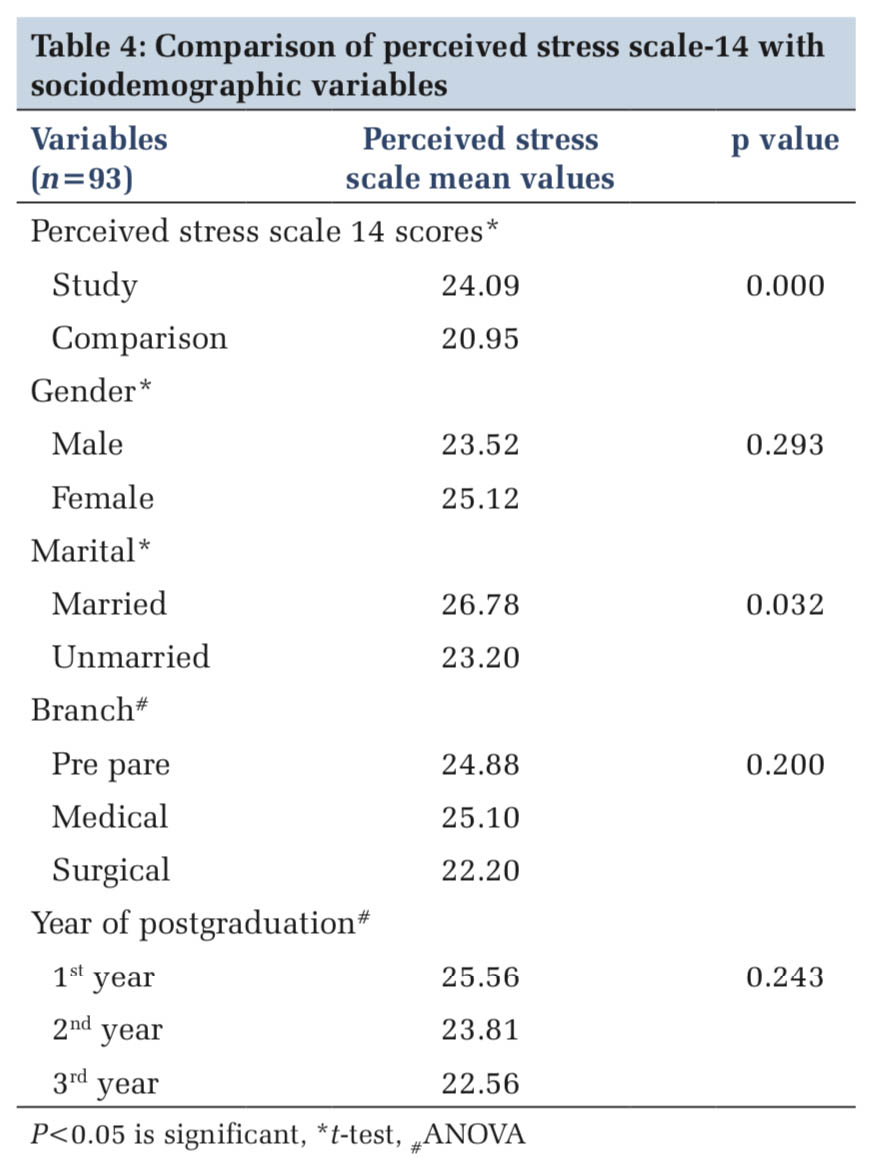

PSS 14 [Tables 3 and 4] Participants’ mean values are compared with the comparison values given by authors for the PSS. The values are available for various socio-demographic variables. Participants have significant perceived stress for age (P = 0.000), gender (P = 0.000), education status (P = 0.000, advanced degree), profession (P = 0.000, professional qualification), employment status (P = 0.044), and marital status (P = 0.000). Using Student’s t-test, PSS mean values of different branches are compared with the comparison sample, there is significant perceived stress in both the pre-para group (P = 0.001) and medical group (P = 0.001), but there is no significant perceived stress in the surgical group (P = 0.444). In between the branches, using ANOVA there is no significant difference in the stress (P = 0.200). Comparison among the various socio-demographic variables of the sample, married have significant perceived stress than unmarried (P = 0.032). We did not find significant findings with other demographic variables.

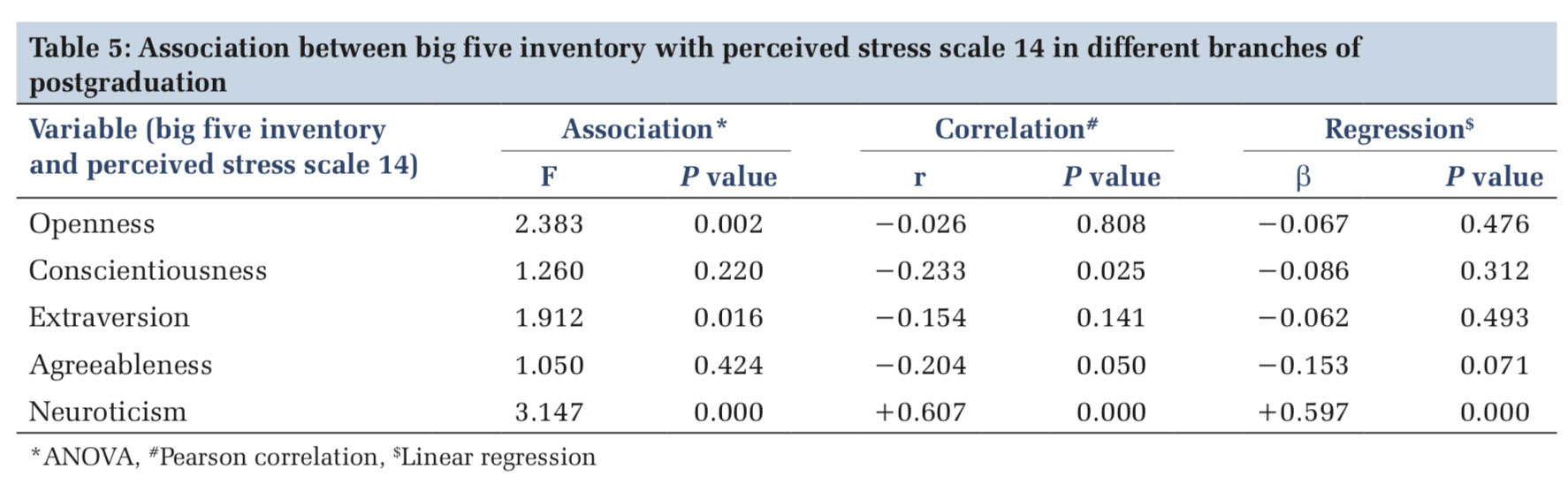

Association between BFI and PSS 14 [Table 5] On comparing mean values of big five personality traits and perceived stress scores, there is significant association with perceived stress with the following personality traits, openness (P = 0.002), extraversion (P = 0.016), and neuroticism (P = 0.000). On doing correlation, there is significant positive correlation between neuroticism and perceived stress (r = +0.607, P = 0.000). There is correlation between conscientiousness (r = −0.233, P = 0.025) and agreeableness (r = −0.204, P = 0.050) traits; which means that there is goodness of fit, but there is no significant correlation (as the r value is nearer to zero) between these variables. On doing linear regression; R = 0.652, R2 = 0.425, and adjusted R2 = 0.392; as R >0.5%, there is association proving a goodness of fit and the difference between R2 and adjusted R2 is 0.033; which does not show chance reason and easily predict that relation exists between BFI and PSS. Taking PSS as dependent variable and personality traits as independent variable, we arrive at an equation {y(PSS)= a0 (24.918) + a1 x1 (openness) + a2 x2 (conscientiousness) + a3 x3 (extraversion) + a4 x4 (agreeableness) + a5 x5 (neuroticism)}. The coefficient for neuroticism trait (+5.180) is statistically significant different from 0 using alpha of 0.05 because its P = 0.000, which is smaller than 0.05.[11]

Personality traits have a strong prediction of perceived stress. A medical professions’ performance and level of care may get affected if the stress levels are high. A review by Doherty and Nugent[12] notes that big five personality traits are a predictor of well-being.

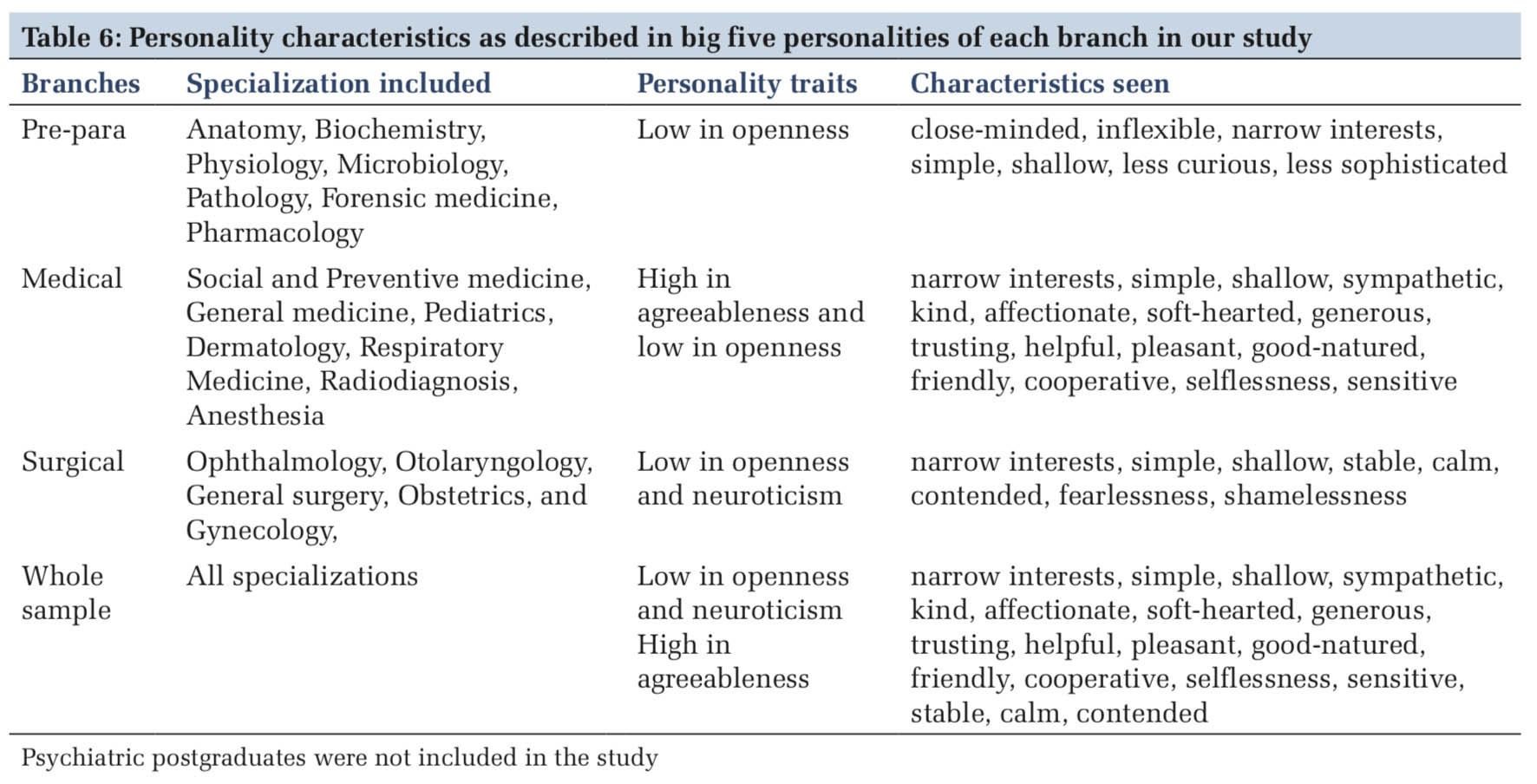

Personality traits in different branches of postgraduation

Pre- and para-clinical branches These branches have less interaction with patients or to an extent work away from the clinical setting. They are involved mainly in teaching undergraduate students and research. Interaction with patients’ may be considered indirect when referred for a specific purpose. The personality traits seen when compared to the general population are low in openness, but among the other branches, they have high openness. This finding of high openness is in line with a study by Mullola et al.,[13] they feel that among the medical researchers there is no patient contact/related work that may focus them towards intellectual curiosity and divergent thinking. This is very much essential in conducting research and deriving appropriate conclusions. Furthermore, innovative techniques in teaching help undergraduate students understand the subject better. Medical branches

These include branches that handle patients with predominantly non-surgical interventions. When compared to the general population they have low openness and high agreeableness, similarly, among the different branches, they have high agreeableness. This is in line with the study by Kwon and Park[14] found that students who have high agreeableness; preferred the medical branch. They felt that as physicians are involved in handling patients and at the same time communicating with paramedical staff, this trait plays an important role. A nation-wide study has also found that high agreeableness is associated with patient-oriented specialties and general practice where characteristics such as sympathy, trustworthy, and cooperation are seen. They have also found that openness is the most consistent trait in physician’s career choices. They felt that low openness is associated with a high or average amount of patient contact.[13]

Surgical branches

These include the branches that are involved in handling the patients using predominantly surgical procedures. We found that have low openness and neuroticism when compared to the general population and low in openness compared to other branches. In line with our study Mullola et al.[13] also found similar findings of low neuroticism. Another study by Maron et al.[15] found that surgical specialty students scored low in openness as compared to other branches, although this finding was not statistically significant. Among the personality measures, neuroticism is the most pervasive trait. It has a good link with negative psychological adjustment and emotional stability. Individuals who score low are less likely to experience negative moods and physical symptoms. It also has a direct link with perceived stress and job satisfaction.[16] The interpretation of this trait being low in surgical branches creates curiosity as to what may be the reason. The low neuroticism in surgeons can explain the low perceived stress seen in comparison to the other branches. We feel that the inherent quality of surgical branches of dealing with prolonged hours and stressful duties attracts people with low neuroticism. On the other side, we feel that low neuroticism also helps a surgeon to take quick and challenging decisions in patient care. Scoring less in this trait is also very important in the healthcare profession, especially with the kind of stress they face in day-to-day practice. The characteristics are summed up and described in Table 6 which is based on the big five theory.[3,17]

We found married scoring high in neuroticism trait. This is in contrast to the study by Kwon and Park,[14] who found that married students scored high in agreeableness, conscientiousness, and significance in neuroticism trait. However, a meta-analysis has found a negative correlation between neuroticism and marital satisfaction.[18] We do not know the reason for the high neuroticism trait in married students. Various reasons are pointed out in the meta-analysis like a negative adjustment or negative interpretation of the events between the partners.

We did not find any gender differences in personality traits between postgraduates of different branches. This in contrast with a study by Lynn and Martin,[19] which was done on a wide sample ranging from 37 different countries and found that women score high in neuroticism and men score high in psychoticism. They felt that their finding is due to the genetic basis and men being more aggressive. Similarly, another study by Weisberg et al.[20] has also reported gender differences in personality traits, with women scoring high in extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Another study by Maron et al.[15] found women scoring higher in extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, but they did not find any difference in neuroticism. Thus, it appears that different studies have reached different patterns of personality traits concerning gender and but there is no consensus between them. There could be a variety of reasons for our finding, some of them may be women being given equal opportunity with men, sharing the same responsibility in patient care as their male counterpart, and it may also be the fact that the selection process of postgraduate is gender-neutral.

Perceived stress

The perceived stress in the study participants is significantly high when compared to comparison sample in various socio-demographic factors such as age, gender, education (mean for an advanced degree, we considered postgraduation as an advanced degree), profession (mean for professional qualification), employment status, and marital status. This shows that medical postgraduates, in general, have high perceived stress when compared to the general population. This is in line with previous studies on postgraduate students.[21,22] In-between the branches, there is no significant difference in perceived stress. This is in contrast to the findings by Ramya et al.,[23] who found statistically significant stress in postgraduates of obstetrics and gynecology followed by pediatrics. They have also found that postgraduates of dermatology have the least perceived stress. This may be because we have not evaluated each branch individually rather grouped the branches for comparison. Hence, in the study, all the postgraduates perceive stress. However, when branches are compared with age-adjusted comparison sample there is significant stress in pre-para and medical branches but not in surgical branches. We were not expecting this finding but it could make sense when seen with neuroticism, which is also low in surgical branches. Married students have reported significant-high perceived stress when compared to unmarried, which is in line with the finding by Gobbur et al.[22] This finding to some extent explains the high neuroticism among married students. Based on the understanding from a study by Harris et al.,[24] who concluded that there are a series of small changes in personality throughout life, but personality may appear relatively stable in short intervals of life, especially in adolescence and early adulthood. Hence, we feel that neuroticism is the reason for high stress among married students.

Big five personality and perceived stress

We found that personality traits; openness, extraversion, and neuroticism are associated with perceived stress in the study. The link is negatively correlated with openness and extraversion, whereas positively correlated with neuroticism. Hence, if the participants score low in openness or extraversion, they have more stress; whereas if they score low in neuroticism they have less stress. With the statistical procedure, it is clear that there exists a goodness of fit between BFI and PSS, even though the r-value is small. This relation explains the study findings of pre-para and medical branches having low openness and high stress; whereas surgical branches having low neuroticism and low stress. We did not find any link between conscientiousness and extraversion with stress in the study. Studies by McManus et al.[25,26] have found that “stress is not a characteristic of the job but of doctors, different doctors working in the same job being no more similar in their stress, and burnout than different doctors in different jobs.”

A high score in agreeableness is not associated with perceived stress. High agreeableness refers to the individual being sympathetic, kind, appreciative, affectionate, soft-hearted, etc. Most of these are positive virtues and hence we feel these may not cause stress. Regarding the conscientiousness trait, it was highlighted in a previous study as being linked with stress,[25] but we did not find such association. This could be because the participants in the study have not shown significant scores in conscientiousness traits compared to the general population and hence no relation to stress. There may be other factors. Indian postgraduate entrance exams tend to assess the candidate’s ability to solve multiple-choice questions in a fixed time interval. Hence, candidates who have good knowledge but are not accustomed to the pattern may not get through; as a result, they will not get the field of their liking and have to adjust with what they are allotted. We feel this could be one of the factors which may lead to mismatch in personality traits with perceived stress. Further research in Indian context should explore this link.

The study has found that medical postgraduates have low openness, neuroticism, and high agreeableness compared to the general population. Among the branches pre-para clinical have low openness, medical have high agreeableness and low openness, whereas surgical have low openness and neuroticism. Some of the traits are useful in the doctor-patient relationship, while others might pose a threat. Some of the good traits which the study finds are sympathetic, kind, affectionate, soft-hearted, generous, trusting, helpful, pleasant, good-natured, friendly, co-operative, etc. Not-so- good traits are narrow interests, shallow, inflexible, less curious, etc. Perceived stress is high in medical postgraduates in all demographic variables compared to the general population. Married show high neuroticism and also high perceived stress. Perceived stress is a positive correlation with neuroticism and negatively with conscientiousness and agreeableness. Perceived stress increases when somebody is less emotionally stable, has poor coping, easy burnout, whereas decreases when they have good pro-social, communal orientation, and good impulse control. Future studies should focus on establishing a personality profile that will better predict future stress coping among the specialist medical doctors by keeping our cultural background into account.

This is a cross-sectional study, a follow-up study will clarify more details; especially on the bidirectional effect of personality and stress. We have assumed that personality traits do not change over the life span. We have not considered the grades/achievements in medical school as one of the variables. This might have further added to the discussion.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.