Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2017.v03i03.004

Year: 2017, Volume: 3, Issue: 3, Pages: 26-28

Case Report

Sukriti Das1, Md. Monirul Islam2, Hasan Mahbub3, Md. Jahangir Alam4, Md. Reaz Ahmed Howlader5

1Associate professor, Department of Neurosurgery, Dhaka Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2MS,

Department of Neurosurgery, Dhaka Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 3Resident Phase-B, Department

of Neurosurgery, Dhaka Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 4MS, Department of Neurosurgery, Dhaka

Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 5MS, Department of Neurosurgery, Dhaka Medical College Hospital,

Dhaka, Bangladesh

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Sukriti Das, Department of Neurosurgery, Dhaka Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Phone: 0088-01711676848. E-mail: [email protected]

Vertebral osteosarcoma is the primary non-hematological malignancy having poor surgical outcome even after all modalities of treatment. We describe one case of vertebral osteosarcoma who initially presented with paraparesis, and subsequently, paraplegia with autonomic involvement. On neurological examination, muscle power was grade “0” of lower limb, sensory level at L1, autonomic absent. Magnetic resonance imaging and plain X-ray reveals collapse of L1 vertebra with intensity changes. She underwent total excision of tumor with posterior decompression by laminectomy of L1 with stabilization by rod and pedicle screw. Post-operative radiotherapy was ensured. The histopathological examination revealed telangiectatic osteosarcoma. Accurate early diagnosis and careful total surgical excision with decompression and fixation of vertebra play an important role. Radiotherapy subsequently helps to the prevention of recurrence and destruction of residual cancer cells.

KEY WORDS:Laminectomy, paraplegia, telangiectatic osteosarcoma, stabilization.

Osteosarcoma is the most common non-hematologic primary malignancy of bone. Primary osteosarcoma of the spine is rare. It accounts for 1.5–4% of all osteosarcoma and 5% of all primary malignant tumors of the spine.[1] In general, it has been reported that primary osteosarcomas affect males more frequently than females, although for those under 15 years of age females have slightly higher rates.[2] Here, we report a case of primary osteosarcoma involving L1 vertebra.

A 14-year-old female presented to us with the complaints of low back pain and weakness in her both legs which were gradually worsened, and she became unable to walk. She also complained of numbness and tinglingsensationinanterioraspectofboththighs. She had also bladder and bowel disturbance. On examination, we found she was catheterized, vitals are normal. On examination, we found an ill-defined, hard, fixed, and tender swelling 7 cm × 3 cm over dorsolumbar region. On neurological examination: Tone was decreased bilaterally; muscle power was grade 0 in all muscle groups of lower extremity. All jerks of lower extremity were absent bilaterally, sensory level at L1. Anal tone was intact. All other systemic examination reveals normal.

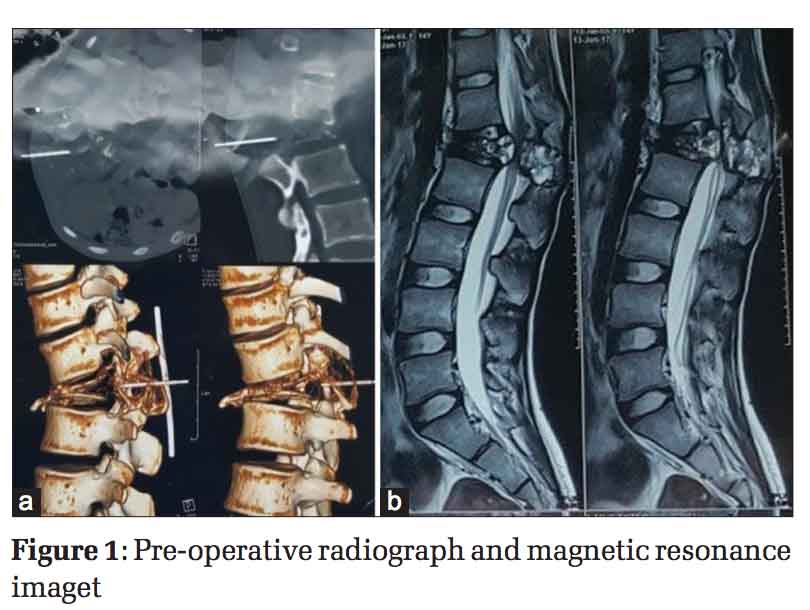

Radiographs demonstrated a collapsed L1 vertebra with evidence of decreased radiolucency, suggestive of a vertebral malignancy [Figure 1a].

Magnetic resonance imaging of lumbosacral spine showed a decreased intensity signal on a T1-weighted image and an irregular high-intensity signal on a T2-weighted image [Figure 1b].

Blood tests show complete blood count: Hemoglobin - 9.2 g/dl, total cholesterol - 8000, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate - 40; chest X-ray P/A view: Normal, MT: 08 mm, and sputum for acid-fast bacilli: Negative, computed tomography guided fine needle aspiration cytology from L1 vertebral lesion shows malignant mesenchymal tumor.

She underwent posterior decompression by laminectomy of L1 with stabilization by pedicular screws and rods [Figure 2]. Radiographs demonstrated stabilization of dorsolumber vertibra by using transpedicular titanium made screws and rods [Figure 3]. The tumor was vascular and fragile and extending to paravertebral space around L1 vertebrae. Post-operative care was adequate, recovery was satisfactory, and muscle power was found 4/5 on the 14th post-operative day, and the sensation was intact. Histopathology report shows telangiectatic osteosarcoma.

Osteosarcomas are primary malignant bone tumors characterized by the production of osteoid or immature bone from malignant cells.[3] Telangiectatic osteosarcoma is an unusual variant of osteosarcoma, forming 3%-10% of all osteosarcomas.[4] There is no significant sex difference. The age of the patients with spinal osteosarcoma ranges from 8 to 80 years (median age, 34.5).[5] Our case is 14 years old.

The most common clinical presentations are pain, neurological symptoms, and palpable mass.[1]

Osteosarcomas have been reported at all levels of the spine. The lumbar and sacral regions are most commonly involved, followed by thoracic and cervical.[6] The most common histologic subtype is osteoblastic; others include chondroblastic, telangiectatic, fibroblastic, and small cell subtypes.[5] Conventional osteosarcomas are high-grade tumors begin in an intramedullary location but may break through the cortex and form a soft tissue mass. The most common locations are the diaphyses of the femur and tibia. Telangiectatic osteosarcoma is a purely lytic lesion.[7]

The most common location at presentation is the metaphyses of long bones, with the following location distribution pattern 11: Distal femur (41.6%), proximal tibia (16.9%), proximal humerus (9.2%), proximal femur (7.7%), mid-femur (6.2%), mid-humerus (4.6%), mid-tibia (3.1%), pelvis (3.1%), fibula (1.5%), skull bones (1.5%), and ribs (1.5%).[4] Vertebral telangiectatic osteosarcoma is rare.

In imaging studies, radiographs and CT scans demonstrate mineralized matrix in the majority of the cases.[5] The majority of the tumors involve the body alone or the body and posterior element. Isolated involvement of the neural arch is rare.[6] Invasion of the spinal canal secondary to a soft tissue mass is common. Involvement of two vertebral levels is seen in 12% cases. Cross-sectional imaging is considered essential for staging and treatment planning for vertebral lesions. CT is useful in assessing the soft tissue extent of the neoplasm. An increase in the attenuation values of the tissue within the medullary canal is generally indicative of tumor extension or “skips” metastases.[8]

The differential diagnosis for spinal osteosarcoma includes any other solitary lytic, sclerotic, or mixed lesion. The one producing the greatest concern is benignosteoblastoma.[9]Otherthanosteoblastoma,the differential diagnosis may include chondrosarcoma and sclerotic metastasis.[8] A few helpful differential points allow a fundamental differentiation of primary versus secondary malignant spinal tumor. The appearance of a soft tissue mass, presence of periosteal response, a long lesion (>6 cm), expansion of bone, and solitary lesion is more commonly found in primary malignant tumors than with secondary ones.[10]

The current treatment protocols for osteosarcoma include of neoadjuvant chemotherapy administered before surgery to decrease surgical morbidity, followed by nearly total tumor mass excision, and post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy to increase systemic control rates.[9] Post-operative radiotherapy may be beneficial.[11] Our patient did not receive pre-operative chemotherapy due to spinal cord compression. A decompressive laminectomy of L1 was performed, the total tumor was removed and stabilization by transpedicular screws and rods.

The prognosis is dismal. The median survival has a range of 6–23 months.[1] The prognosis is poor primarily because the lesions are usually large at presentation and cannot be completely excised majority cases.[12] Patients with metastasis have poor surgical outcome.

In summary, we report a rare case of primary osteosarcoma of the lumber spine presented with complete paraplegia with autonomic dysfunction. In advanced world, these patients are usually treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and if needed surgery. We successfully did decompression and removal of tumor elements and fixation which allow her early mobility and neurological return of almost normal. Radiotherapy was given to prevent recurrence. Now, after 1-year follow-up, she is leading almost normal life without any recurrence.

Dhaka Medical College, Topbright.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.