Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2018.v04i01.007

Year: 2018, Volume: 4, Issue: 1, Pages: 29-32

Case Report

Shailendra Yadav, Sanjay Chawhan*, Vrushali Shroff, Jayashree Tijare, Balwant Kowe, Waman Raut

Department of Pathology, Government Medical College and Hospital, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Sanjay Chawhan, Department of Pathology, Government Medical College and Hospital, Gondia, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. Phone: +91-9823642628. E-mail: [email protected]

Anal melanoma is a rare and aggressive gastrointestinal tract malignancy that is locally invasive and metastasizes early in the course of the disease. Clinically, it is often misdiagnosed with other anorectal conditions with an overall poor prognosis and poor survival rate. We report a rare case of 66-year-old female presenting with altered bowel habits and bleeding per rectum. She was having a rectal mass which was resected and sent for histopathology examination. With the help of immunohistochemistry, final diagnosis of malignant melanoma was done.

KEY WORDS: Anal, gastrointestinal tract, melanoma, immunohistochemistry.

The anal melanoma (AM) is a tumor of melanocytes that produce melanin. Moore described AM for the first time in 1897. The most common sites of melanomas in decreasing order are the skin (91.2%), eyes (5.2%), and the anorectal region (< 1%). AMs occur more frequently in sixth to eighth decades of life and are more common in women. The etiology of AMs is associated to exposure of the skin to ultraviolet rays. This explains the rarity of the site of the anorectal region which is not exposed easily.[1] AM is a very rare disease with a very poor prognosis due to its unclear presentation at the time of diagnosis. The prognosis depends on the tumor size, the depth of invasion, and also cell proliferation markers.[2] It is most commonly seen in adults with complaints of rectal bleeding, pain, and palpable mass having an aggressive clinical course with distant metastasis to lymph node as well as liver.[3] AMs similar to melanomas from other mucosal sites may harbor activation KIT mutations and respond to tyrosine kinase inhibitors therapy, though surgical excision is mainstay of treatment.[2]

On histological (hematoxylin-eosin) examination of the lesion, idea about cell type, degree of melanin pigmentation, and mitotic index is obtained. Different forms of melanocytes such as epithelioid, lymphoma- like, spindle-cell, and pleomorphic can be seen that makes the differential diagnosis of some diseases such as Paget, Bowen, lymphomas, undifferentiated carcinomas, sarcomas, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Thus, especially in amelanic AMs (but also in melanocytic ones), immunohistochemistry should be performed - the study of protein expressions of melanocytes.[1]

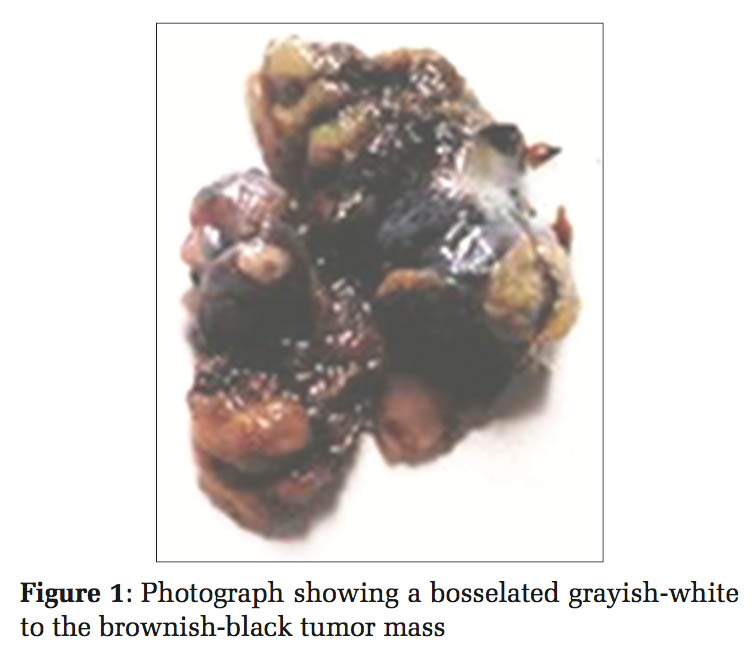

A 66-year-old female presented in the casualty department with a history of profuse rectal bleeding, pain, and weight loss with malaise. On inquiry, the patient gave a history of altered bowel habits for 6 months. Mass per rectum [Figure 1] of size 4 × 2.2 × 1.4 cm was noted on local examination which is grayish-white to brownish-black, soft to firm, and bosselated. No remarkable past medical or family history was obtained. The patient was operated, and the mass was submitted for histopathological examination.

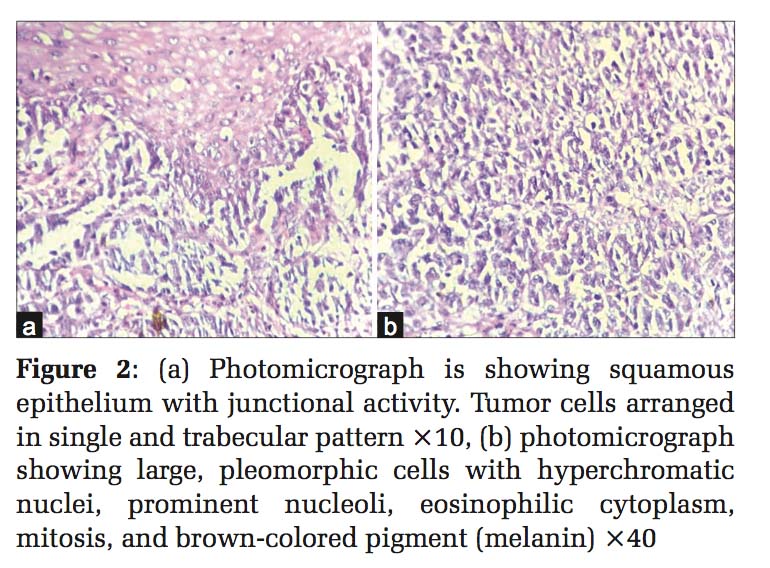

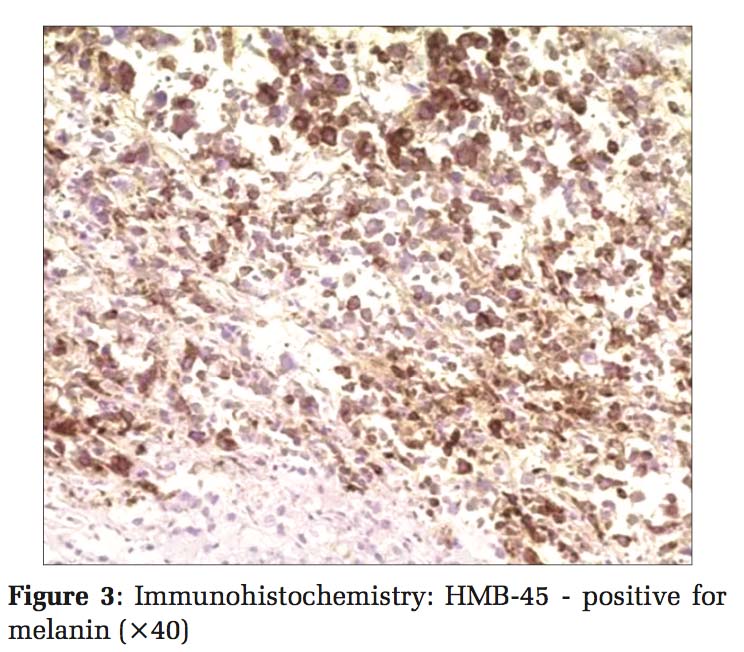

The sections studied from the tumor mass show stratified squamous epithelium lining. The subepithelium shows tumor cells arranged in the single and trabecular pattern [Figure 2a]. The individual cells are large, pleomorphic with hyperchromatic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and eosinophilic cytoplasm. Tumor areas showed increased mitosis. Few areas show cytoplasmic brown-colored pigment (melanin) [Figure 2b]. Immunohistochemical stain for HMB-45 was positive [Figure 3].

Based on histomorphology, special stains, and immunohistochemistry, diagnosis of malignant melanoma was given.

AMs are a very rare disease with 1:8 and 1:250 of squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma in anorectal region, respectively. It accounts for 1–3% of all anal tumors and 0.3% of all melanomas.[4] Approximately 1.2% of all melanomas are mucosal, of which < 25% are anorectal melanomas. After cutaneous and ocular melanomas, anorectal region is the third most common location. In addition,themostcommonprimarymelanomaof the gastrointestinal tract is AM which accounts for 0.5% of all colorectal and anal cancers approximately.[5] The incidence is most commonly presenting during 5th–6th decades predominantly among Caucasians. The most common location of tumor is dentate line which appear as polypoidal masses covered with smooth surface spreading along the submucosal planes. Therefore it is rarely completely resectable at the time of diagnosis. The exact etiology is not known.[3] AMs are very difficult to diagnose as patients present late, non- specific complaints, anatomic location of tumor. The most common presenting complaint is rectal bleeding (55%), perianal or rectal mass (34%) with other complaints of pain, pruritus, and alteration of bowel habits, tenesmus, prolapsed hemorrhoids, and diarrhea.[3] AMs are frequently misdiagnosed as prolapsed hemorrhoids, so it is imperative to have a high index of suspicion and fully evaluate all complaints of lower GI bleeding and pain.[6] A colonoscopy with tissue biopsy is important for diagnosis. Endorectal ultrasound may be considered to evaluate tumor thickness and surrounding nodal status. Imaging techniques such as computed tomography scan (abdomen and pelvis) are utilized to determine if metastasis or lymphadenopathy is present.[2] Metastatic disease is likely to occur in the liver, lung, or pelvis and imaging should be directed at the systems. Ultrasonography has become an important staging tool for rectal adenocarcinoma, but its role in melanoma remains unclear.[7] Histopathological examination reveals the diagnostic features of malignant melanoma such as cytoplasmic brown- to black-colored melanin pigment and junctional changes. The junctional changes imply the presence of a malignant tumor with atypical epidermoid cells adjacent to it; otherwise, diagnosis of melanoma depends on the use of immunohistochemistry.[8] Histological markers may also be used.[2] Amelanotic tumor can be seen in 30% of the cases and show some morphological variation which can be misdiagnosed as lymphoma, carcinoma, or sarcoma. Immunohistochemistry markers including S-100, Melan A, HMB-45, tyrosinase, and vimentin are frequently used.[5] In our case, HMB-45, a immunohistochemistry marker for melanin, was positive [Figure 3]. The main treatment modality is surgery with the major goal of improving both quality and quantity of life because cure is difficult with such an aggressive disease.[6] There is no adjuvant therapy dictated as the standard of care in anorectal melanoma particularly in metastatic disease.[2] After diagnosis, the total survival time is 10–19 months and <10% cases show 5 years survival.[6] Due to rarity of AM and little reporting in the literature, it is difficult to conclude regarding best treatment and outcome.[2] Consensus is not available, stating surgery is favorable approach due to rare occurrence of this entity. The surgical procedure of choice available is an abdominoperineal resection to wide local excision with or without adjuvant radiotherapy.[9] It is a topic of debate about treatment approach of AM. Data on the utilization of medical therapy for AM are not proven at present, although a trial of multiple treatment options such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy has been done.[10]

AM is an aggressive and rare gastrointestinal malignancy with a predilection for early infiltration and distant spread resulting in a very poor prognosis. In spite of available different options of therapy such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the prognosis of AM is not favorable. Due to its various histological forms, AM can be suspected as one of the differential diagnosis at this site and immunohistochemistry is essential for attaining a definitive diagnosis.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.