Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.v12.i1.25.74

Year: 2025, Volume: 12, Issue: 1, Pages: 1-8

Original Article

Sushma Krishna1 , C Kavya2 , N Sandeep3 , P M Mohammed Nehel2 , M Mohammed Faseeh2 , M Apoorva Dev4

1Associate Professor, Department of Microbiology, PESUIMSR, Bangalore, 560100, Karnataka, India,

2Pharmacy Intern, East West College of Pharmacy, Magadi Road, BEL layout, Bangalore, 560091, Karnataka, India,

3 Infection Control Nurse, Sagar Hospitals, Bangalore, 560041, Karnataka, India,

4Professor & Head, Department of Pharmacy Practice, East West College of Pharmacy, Magadi Road, BEL Layout, Bangalore, 560091, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence: Sushma Krishna, Associate Professor, Department of Microbiology, PESUIMSR, Bangalore, 560100, Karnataka, India.

E-mail: [email protected]

Received Date:19 February 2025, Accepted Date:04 July 2025, Published Date:30 November 2025

Background: Infections caused by Multidrug Resistance Organisms such as by Carbapenem Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli have emerged as a potentially fatal challenge for clinical management in the health care set ups in India. These organisms also present challenges in hospital IPC practices. The objective was to analyse the spectrum of infections, and clinical outcome in Carbapenem Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli isolated in hospitalized patients, to estimate the high-end antibiotic consumption, document the Infection Prevention Control Surveillance Practices and corresponding hospital antimicrobial stewardship measures.

Methods: A retrospective study was conducted at a 450 bedded medium sized private tertiary hospital. Data was collected from Microbiology Laboratory, Medical Records Division, Infection Control Department, and Pharmacy Section from January- September 2023 of consecutive 181 patients who were administered selected four high end antibiotic therapy.

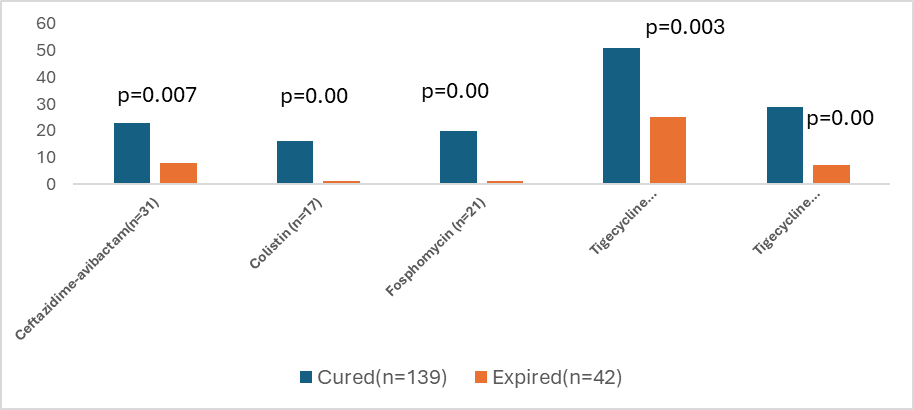

Results: Laboratory data showed 87 isolates as Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae from 149 Gram Negative Bacilli (58%). Tigecycline monotherapy was the highest administered (n=76, 42%), followed by 19.8%(n=36) of tigecycline combination with colistin or others. Higher number of patients (n =89, 49 %) with Sepsis/related syndrome patients grew Multidrug Resistance Organisms. The number of course of Tigecycline (most prescribed) was n=110, 50.93%, followed by ceftazidime avibactam (n=44, 20.37%), Colistin (n=36,16.67%) and Fosfomycin (n=26,12.04%). Tigecycline showed the largest usage (51%) and consumption (63.3%) by different calculations when compared with others. The calculated Prescribed to defined daily dose ratio showed the over-utilization of Tigecycline (1.50) and Fosfomycin (1.33). The clinical outcome of the four high end therapy administered that were studied was found to be statistically significant in all groups (p<0.05). Hospital Infection control practices showed adherence to Infection Control policy but there was no synergy in tracking the multi drug resistant organisms and Anti-Microbial Stewardship interventions.

Conclusion: There is over prescription of the last few reserved antibiotics available in market. As the emerging drug resistance scenario is worsening, pharmacists driven by stewardship practices must synchronize with Infection Control Nursing Practice for better patient care. Stewardship measures from the clinical laboratory microbiologists must also be stepped up to conserve the last few available antibiotics for the coming days. Hospital Quality Improvement teams may bridge these fragmented practices.

Infections caused by Carbapenem Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli (Carba- R GNB) have emerged as a potentially fatal challenge for clinical management in the health care set ups in India. These organisms are placed under the WHO Priority 1 critical list which require the use of few available reserve group of antibiotics that are "last resort" treatments when 1, 2, 3, 4. High dose carbapenems, Colistin, Tigecycline, Ceftazidime-avibactam, Fosfomycin are the currently available options at hand for addressing these Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) and CRABs (Carbapenem Resistant Acinetobacter Baumanni). Ceftazidime- avibactam, novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors is a recommended choice, but clinical isolates with resistance are emerging. For CRE with resistance to novel agents and for CRAB, combination therapy of old drugs, including polymyxin, tigecycline, minocycline, and aminoglycoside are recommended, especially in those with moderate-to-high disease severity. However, the optimal combination regimen of antibiotics remains uncertain. The recent IDSA, ESCMID guidelines support using high dose Tigecycline combination regimens against CRE & CRAB 5, 6, 7, 8.

Local Antimicrobial stewardship programs (AMSPs) which many tertiary centres have in place, are critical in for optimizing the use of antibiotics to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR), improve patient outcomes, and reduce healthcare costs. The usage of the reserved drugs should be tailored for very particular patient and settings to maintain their efficacy for the future days. Pharmacists are expected to contribute to AMSPs by conducting regular reviews of antibiotic prescriptions, identifying inappropriate use, and recommending alternatives or adjustments based on clinical guidelines, culture results, and patient-specific factors. Their involvement in AMSPs in monitoring antimicrobial usage will not only enhance patient care but also is foreseen to contribute to the overall effectiveness and sustainability of hospital-based antimicrobial stewardship initiatives in conserving the reserved antibiotics. 9

At the same time, the emergence and transmission of MDROs have important infection control nursing implications in hospitals. As the hospitals vary in physical and functional units, the approaches to prevention and control of these pathogens need to be tailored to the specific needs of each population and individual hospitals. Most tertiary hospitals have an Infection Prevention Control program in place, but MDRO surveillance is not rigorous 10. The Infection Control Nurse taking up this surveillance mostly needs resources from hospital administration such as additional staff and prompt laboratory support for adherence monitoring and data analysis. The integration of AMSP, pharmacy and IPC programs which otherwise is easy from the overlapping team members, becomes a burden or gets fragmented with numerous committee members. The study aimed to describe the Carbapenem Resistant MDROs in a tertiary set up and related high-end antibiotics use as opportunities for effective antibiotic therapy and strengthen the infection control measures in preventing MDROs transmission.

To analyse the spectrum of infections, and clinical outcome in Carba-R-GNB isolated in hospitalized patients.

To estimate the selected high-end antibiotic usage and consumption in the infections caused by Carba-R-GNB.

To document the infection control practices with corresponding antimicrobial stewardship measures followed for reported Carba-R-GNB.

Study Center: A retrospective study was conducted at a 450 bedded medium sized private tertiary hospital. Data was collected from multiple sources within the period January-September 2023.

Data collection : The case charts of consecutive patients with cultures growing MDROs were reviewed from the Medical Records Section for Clinical diagnosis of the patient, therapy administered, clinical significance and outcome of the patients. Culture reports with growth of Carbapenem-R-GNBs were accessed from microbiology laboratory for bacterial profile and Anti-Microbial Susceptibility patterns. The antimicrobial susceptibility tests to carbapenems, colistin, Fosfomycin (UTI) were carried out by MicroScan Walk Away Plus ID/AST System (Beckmen Coulter, US) according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, M100, 27th edition) recommendations 11. Surveillance Data on prevalence rates, sites of infection, patient location, infection control measures practiced were recorded from Hospital Infection Control Department. High end or reserved drug antibiotic consumption data was procured from pharmacy section. The eligibility group was predefined; it was a non-probability sampling method of available subjects in the study duration. A complete view of this specific group was captured without pre-determined sample size. Study had the hospital IEC approval EWCP/SH/22-23/15; dated 17/04/2023.

Definitions: Carbapenem resistance was defined as resistance to imipenem or meropenem (imipenem or meropenem MIC ≥ 4 mg/L for Enterobacterales and MIC ≥ 8 mg/L for Acinetobacter spp.) 12 Susceptibilities of tigecycline were determined as per FDA standard (MIC ≤ 2 mg/L, sensitive; MIC = 4 mg/L, intermediate; MIC ≥ 8 mg/L, resistant) 13. MDRO was defined as organism with acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories 14. Three different metrics were used for consumption calculation- a) WHO/ATC DDD standards, b) the number of treatment course and the days of the therapy c) PDD/DDD ratio. PDD was defined as Total amount of drug prescribed(mg)/Number of patient days. DDD was represented as Standard dose defined by WHO. PDD/DDD ratio >1: Consumption was regarded crossing standard DDD, drug over utilized. PDD/DDD ratio is <1: Consumption was regarded as not crossing the standard DDD, drug underutilized. 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

Exclusion criteria: Samples growing Gram Negative Bacilli with inherent resistance to carbapenems were excluded from the study, Patients in whom carbapenem was administered as high-end therapy and patients on empirical therapy with any of the studied antibiotics were also excluded.

The total number of in-patients who were prescribed antibiotics during the study period was 3196 and at ICU was 1574. A total of 181 patients were prescribed studied high-end antibiotics (Ceftazidime-avibactam, Colistin, Fosfomycin and Tigecycline). Among these patients, 110 (60.7%) were male and 71 (39.2%) were female. The reserved antibiotic use was prominent in patients over 50 years old (n=148, 81.7%). The median length of hospital stay in 49% (n=89) of patients was around 10.5 days (IQR 6-16). Upto 89%(n=161) patients had associated co-morbidities with DM, HTN, CKD etc. Table 1 shows the Clinical diagnosis and high end definitive antibiotic therapy administered to patients with MDRO infections.

|

Clinical Diagnosis (N=181) |

Ceftazidime –avibactam +/- Aztreonam N=31(%) |

Colistin N=17 (%) |

Fosfomycin N=21 (%) |

Tigecycline monotherapy N=76 (%) |

Tigecycline in combination# N=36 (%) |

|

Sepsis/ related syndrome/shock (all source combined) (n=89) |

9(29) |

5(29.4) |

11(52.3) |

53(69.7) |

11(27.7) |

|

UTI (n=34) |

7(22.5) |

2(11.7) |

7(33.3) |

10(13.1) |

8(22.2) |

|

LRTI/Pneumonia (n=15) |

3(9.6) |

5(29.4) |

0 |

2(2.6) |

5(13.8) |

|

Wound infection (n=34) |

4(12.9) |

1(5.8) |

2(9.5) |

6(7.8) |

2(5.5) |

|

Others* (n=28) |

8(25.8) |

4(23.5) |

1(4.8) |

5(6.5) |

10(27.7) |

*Others included cardiac, renal and gastro related.

# Combination therapy: Colistin+ Fosfomycin+ Tigecycline(n=1), Tigecycline +Fosfomycin(n=3), Tigecycline+ Colistin(n=7), ceftazidime-avibactam+Fosfomycin+Tigecycline +Colistin(n=1), ceftazidime-avibactam+Tigecycline(n=5). Carbapenem therapy excluded.

No. of patients among the above had culture negatives but treated with high end antibiotics n=32.

No. of patients among above in whom cultures were not tested but treated with high end antibiotics n=14.

Tigecycline monotherapy was the highest administered (n=76, 42%). The mean duration of tigecycline monotherapy was 6.2 ± 5 days with 11.10 ± 9.23 doses followed by colistin of 5.41 ± 6 days with 10.29 ± 11.21 doses. 19.8%(n=36) were administered a tigecycline combination with colistin or others. Tigecycline monotherapy was administered in highest numbers of patient with sepsis/septic shock (all cause) i.e. 53 (69.7%). It was found to be curing 67% (n=51) of patients (p=0.003) (Figure 1). Fosfomycin and ceftazidime-avibactam were equally administered in uncomplicated UTI patients (n=7, 20%). Fosfomycin known to have variable activity against carbapenemases, therapy duration (7-10 days) and the dose administered were compliant. So was colistin, with dose and therapy duration (7-14 days). The feedback, persuasions from AMSP team covered <50% of the documented cases(n=40). There were 32 culture negative patients who were administered high end antibiotics without de-escalation with missed clinical opportunities. The colonizers with asymptomatic patients, as assessed by the infection control team, were also treated with high-end therapy (n=13).

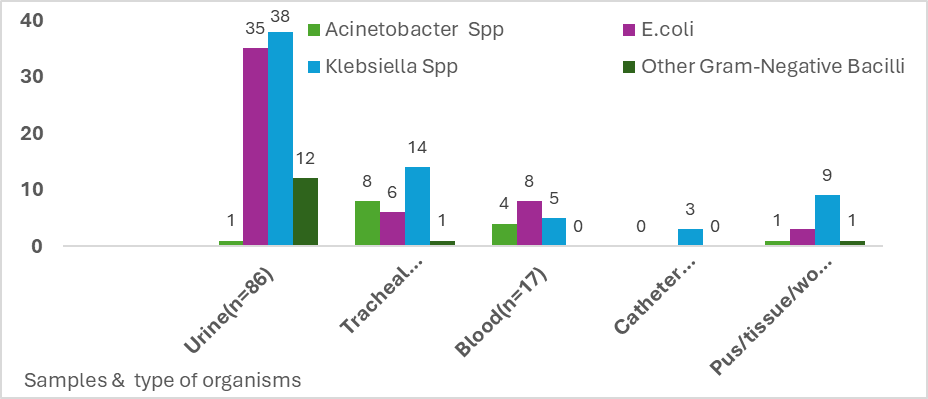

Out of the 3600 samples processed for cultures, 1080 were culture positive. MDRO positivity culture rate from total samples was 2.4% (n=87) from 149 patients from the Medical Records reviewed. Blood cultures showed E. coli (n=8), Klebsiella spp. (n=5), Acinetobacter (n=4). Urine cultures showed the maximum growth of E. coli (n=35), Klebsiella spp. (n=38) and others (n=12). Exudates cultures showed Klebsiella spp. (n=9), E. coli (n=3), others (n=2). Tracheal cultures showed Klebsiella Spp (n=14), E. coli (n=6), others (n=9) (Figure 2). Tigecycline monotherapy was most used for samples growing E. coli (n=18) and Klebsiella spp. in total (n=24). Resistant rates of these MDROs were higher to other antibiotics such as cotrimoxazole (99%), fluoroquinolones (98%) (levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin), and nitrofurantoin (urine isolates 95%). Amikacin, however, remained 53% sensitive.

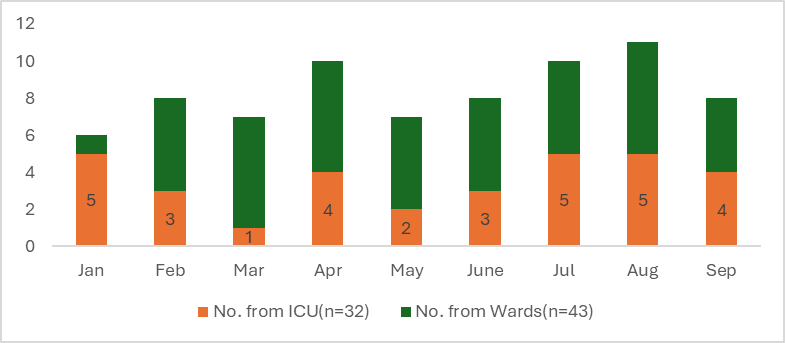

There was evidence of the Laboratory staff promptly passing on the MDRO isolations to IC team. These patients were actively followed up till their discharge by the ICN. Most were tracked from wards (n=43 out of 75) (Figure 3), relevant transmission based precautionary measures were employed at respective locations and were monitored for an average of 7 days. Cleaning and disinfection practices were employed as per the hospital’s policy, irrespective of pathogen or colonization status of MDRO. Hand hygiene compliances at these places were found to be 70-75% on average. PPE usage audit revealed 60-70% compliance. Fourteen out of 21 HAIs during the study period were from MDROs: CAUTI(n=7), CLABSI(n=3), VAP(n=2), SSI(n=1) of which the SSI and two CLABSI patients expired and were documented as hospital’s sentinel events. There was no further transmission/cross-transmission of the organisms as multiple concurrent infection control measures were employed. No outbreaks were detected. There were no traceable MDROs in the environment and active surveillance cultures (air and surface) from multiple locations continued as per the hospital policy.

The number of courses of Tigecycline (most prescribed) was n=110, 50.93%, followed by ceftazidime avibactam (n=44, 20.37%), Colistin (n=36,16.67%) and Fosfomycin (n=26,12.04%). Tigecycline showed the largest usage (51%) and consumption (63.3%) by different calculations when compared with other antibiotics (Table 2).

|

|

A |

B |

||||

|

Antimicrobial agent |

Number of courses |

% Use * |

DOT |

Average Days of prescribing § |

DOT/1000 PD † |

% Consumption ‡ |

|

Colistin |

36 |

16.67 |

142 |

3(1-5) |

71.29 |

14.23 |

|

Ceftazidime- avibactam +/-Aztreonam |

44 |

20.37 |

172 |

3(1-5) |

86.35 |

17.23 |

|

Fosfomycin |

26 |

12.04 |

54 |

2(1-3) |

27.11 |

5.41 |

|

Tigecycline |

110 |

50.93 |

630 |

5(1-9) |

316.27 |

63.13 |

5-7 days of all agents=1 course, 48 hrs gap-Next course.

% Use – no. of treatment courses of particular agent/total number of treatment course.

DOT=Days of therapy, PD=patient days, *number of courses per class×100/total courses of therapy (216); † DOT/1000PD, days of therapy per 1000 patient days (1992); § median (range) days of prescription.

‡ (DOT/1000PD per class×100)/aggregate DOT/1000PD of all antimicrobials (501).

The calculated PDD/DDD ratio for Fosfomycin (ATC Code JO1XX01) and Tigecycline (ATC code J01AA12) consumption was 1.33 and 1.50 respectively compared to WHO reference standard of 1, suggesting over utilization of Fosfomycin and Tigecycline in the hospital.

The role of pharmacists is vital in AMSP implementation. Studies mostly use WHO/ATC defined daily dose (DDD) to quantify antibiotic consumption in adult population. While days of therapy (DOT) based metrics regardless of the dose has been the other measure used, PDD is a better weight-based measure but may vary depending on the severity of infection and so on. Every metric has its own advantages and disadvantages and have differences in indications or recommendations. These metrics also come with challenges in measuring them on routine basis 21, 22. We attempted calculating the consumption by different methods to arrive at the results of excessive use of Tigecycline in hospital beyond the references set. The laborious calculations if undertaken by the pharmacists makes a case to the prescriber seeking numbers to clinically translate this information. This antibiotic is not listed as reserved by WHO and its use is indicated only in intraabdominal and skin and soft tissue infections in the country. Its use has remained controversial in nosocomial pneumonia and UTI.

The study does have limitations- while automated culture results do mention the resistance gene of NDM, OXA, KPC etc carried by Carba R gram negative organisms, in most medium sized hospitals, further typing or identification of carbapenemase gene testing for confirmation is not available to justify the selection of these reserved drugs and the ICMR guidelines unfortunately rely heavily on the same. 23, 24. Also, an in-depth subgroup analysis has not been carried out as the pharmacy results, by themselves, may not present a complete meaning. Nevertheless, there is a well-knit link between infections, antibiotic usage, resistance and MDRO emergence 25. One of the ways to delay the emergence of antimicrobial resistance is by addressing the high-end usage either at front end or at back end by the AMSP stewards who mostly are clinical laboratory microbiologists in India. Despite having a functional IPC program and a partially functional AMSP at our hospital from over a decade, there were missed opportunities/consultant (upto 20-30 %) in providing right recommendations such as in asymptomatic colonization, timely de-escalations, nonadherence to policy and reviews on day 3 etc. We agree that prescribing patterns involves behavioural changes as rightly mentioned by Charani et al and requires prompt owning up from clinicians or prescribers themselves. 26, 27

Parallelly, preventing infections and further colonization with adequate Infection Control measures is known to reduce the burden of MDROs in healthcare settings. The HAIs caused by MDROs were higher as it is from other studies 28 and it is here the role of Infection Control Nurse is highlighted. There was a clear discrepancy between the number of patients with MDROs tracked, patients receiving high end antibiotics for MDRO positive culture, and the number reached for antibiotic recommendations suggesting a fragmentation and discontinuity in care. The Laboratory Information digital reporting systems employed may send alerts to ICN for MDRO surveillance and to Hospital AMSP team simultaneously to monitor the antibiotic usage. If initiated, this interface with Hospital Information Management System (HIMS) can become a reality for quality accredited hospitals such as ours.

The study highlights the importance of integration of all three domains of hospital in delivering safe patient care. We suggest that the Hospital Quality team, overseeing the continuous quality improvement, takes proactive measures in bridging the missing links from the three ends with adequate backing from hospital administrators.

The study showed the high-end reserved antibiotics being used excessively in the city’s hospital and this is an alarming pattern. Hospital Pharmacists need to be actively involved in consumption data audits and track the usage periodically with timely feed-back to clinicians as a part of stewardship measure. Hospitals which are pro-technology may bring in digital solutions or computerized pharmacy data to collect, analyse and subsequently monitor consumption/usage as manual calculations are cumbersome and tedious. Integration of IPC-AMSP practices is a requirement. Addressing the challenge of Carba -R GNBs locally as a combined responsibility of the AMSP, Pharmacy, IC and Quality improvement teams will be a drop in the mighty ocean. It is about time the hospital AMSP committees stopped being a mandatory medical council or accreditation requirement on paper and braced up to conserve the last few available antibiotics today.

Carba-R-GNB: Carbapenem Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli

CRE: Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacterales

CRAB: Carbapenem Resistant Acinetobacter Baumanni

AMR: Antimicrobial Resistance

AMSP: Anti-Microbial Stewardship Program

IDSA: Infectious Disease Society of America

ESCMID: European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

MDRO: Multi Drug Resistant Organism

IPC: Infection Prevention Control

WHO/ATC: World Health Organization/Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical

ICN: Infection Control Nurse

PDD: Prescribed Daily Dose

DDD: Defined Daily Dose

DOT: Days of therapy

UTI: Urinary Tract Infection

CAUTI: Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection

CLABSI: Central Line Associated Blood Stream Infection

VAP: Ventilator Associated Pneumonia

HAI: Hospital Acquired Infection

To the hospital management team, Sagar Hospitals, Bangalore where the study was conducted.

Funding: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.