Introduction

Ventral hernias are a common surgical challenge, requiring effective and durable repair to prevent recurrence and ensure optimal patient outcomes. Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair (LVHR) has become an extensively adopted approach, offering advantages such as reduced postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, and quicker recovery compared to traditional open techniques. 1 Mesh fixation is a critical step in ensuring the long-term success of LVHR, with various methods employed to secure the mesh in place. 2 The reported recurrence rate after LVHR ranges from 2 to 3%. 3 Compared to other minimally invasive procedures, LVHR causes a considerable amount of pain in the postoperative period. This self-limiting pain can last as long as 2 weeks and can also become chronic pain, which can last for more than 8 weeks. The cause of this postoperative pain has been attributed to the mesh fixation technique. 4

CapSure™ Permanent Fixation System device fixation (poly-ether-ether-ketone PEEK), ProTack™ Fixation Device (Titanium Helical fastener), and suturing with 2-0 polypropylene represent three widely utilized approaches, each with its own set of advantages and potential drawbacks. 5 The outcome of the surgery depends on the stability of the mesh, which will impact the recurrence rates. CapSure™ Permanent Fixation System involves the use of a specially designed tacking device to affix the mesh securely to the abdominal wall. 6 ProTack™ Fixation Device device fixation, on the other hand, utilizes a different type of tacking device to secure the mesh. Suturing with 2-0 polypropylene involves traditional surgical sutures to attach the mesh to the abdominal wall. While mesh fixation is crucial for preventing hernia recurrence, it is essential to consider the potential complications associated with each fixation method. Common complications may include infections, seromas, and chronic pain.7 By thoroughly assessing and comparing these complications across the different mesh fixation methods, the study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the overall safety profile of each technique. Beyond the technical aspects of mesh fixation, patient-reported outcomes play a crucial role in evaluating the success of hernia repair procedures. The occurrence of complications can lead on to patient dissatisfaction and can impact the overall outcome of the procedure. By incorporating patient perspectives into the evaluation, the study aims to provide a more holistic understanding of the outcomes associated with CapSure™ Permanent Fixation System, ProTack™ device fixation, and suturing with 2-0 polypropylene in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair.

Material and Methods

An observational study was conducted at the minimal access surgery department of a tertiary care hospital between September 2023 and January 2024. The institutional ethics committee approved this study’s protocol. Patients aged above 18 years who require non-emergency ventral hernia repair were included in the study. Patients with contraindications for laparoscopic surgery, such as chronic cough, active infection, loss of abdominal domain or ascites, were excluded from the study. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants, and data confidentiality was maintained throughout the study. The type of mesh fixation technique to be used for the patient was decided by the operating surgeon. Based on the fixation technique used, patients were divided into groups. Group A are patients in whom CapSure™ Permanent Fixation System was used to fix the mesh, Group B are patients in whom ProTack™ Fixation Device was used, and group C are those in whom suturing with 2-0 polypropylene was used.

Operative techniques

All patients were placed under general anesthesia for the operation. In all cases, LVHR (Ipom plus) Pneumoperitoneum was obtained using either a Veress needle or an open technique. 8 A 30° camera was inserted through a 10-mm trocar. Other trocars were inserted under direct visual. When necessary, adhesiolysis was performed, the hernia was exposed, and defect closure was done with barbed suture. The surrounding area was prepared for mesh placement. All patients were given a 1-mm-thick expanded polytetrafluoroethylene mesh tailored to overlap all hernia margins by at least 5 cm.

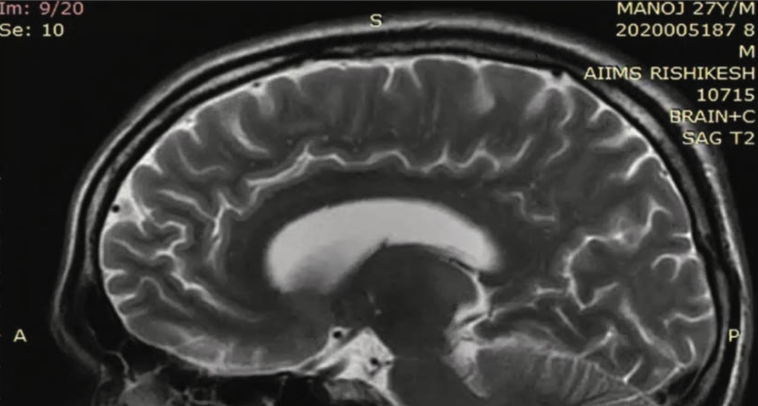

The method of mesh fixation for each patient was determined by the operating surgeon and patient acceptability. Group A- CapSure™ Permanent Fixation System (poly-ether-ether-ketone PEEK) (Figure 1), Group B- ProTack™ Fixation Device (Titanium Helical fastener) (Figure 2), and Group C- suturing of mesh with 2-0 polypropylene (Figure 3) were done. After fixation of the mesh, the trocars were removed, and the pneumoperitoneum was released. Fascial closure was done at all trocar sites that were 10 mm in diameter or larger. No special bandages were applied. Immediately after the operation, the surgeon completed a detailed report on patient, hernia, and operative characteristics.

All patients received standard postoperative care, including mobilization and a return to normal diet, as quickly as possible. Patient-controlled analgesia was provided for the first 24 hours after surgery. Even patients with minimal pain or discomfort were given paracetamol (1 g three times daily). The postoperative analgesia management was as per protocol for all patients.

Clinical follow-up

All patients were scheduled to return for an outpatient visit 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months after surgery. The primary outcome measure in the study was the presence and severity of postoperative pain, as determined by scores on a visual analogue scale (VAS; range 0–100) obtained preoperatively (baseline) and during the outpatient visits. The study also assessed the QoL by means of the administration of the RAND 36-item Short-Form Health Survey 1.0 (SF- 36) preoperatively and at all the follow-up visits. 9 Seromas and hematomas were considered complications when they limited daily activities or required drainage. Hernia recurrences were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The data collected was entered into an Excel sheet using MS Office 2007. Descriptive statistics were employed to present frequency (percentage) for categorical factors, while continuous factors were represented by Mean ± SD. For skewed data, the median with interquartile range was utilized. The normality of the data was assessed through the Shapiro-Wilk test. To explore the association between clinical profile and demographic factors, Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was applied. To identify significant differences between groups, the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was employed. Statistical significance was considered for P-values < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.0 software.

Results

Demographic

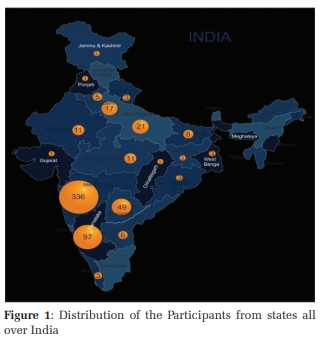

A total of 50 patients were studied. The mean age of the study participants was 51.6 years with a standard deviation (SD) of 10.8 years. The gender distribution showed 29 males (58%) and 21 females (42%). The mean BMI of the participants is 28.8 kg/m² with a standard deviation of 4.8 kg/m². The American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) classification of the participants shows that the majority are classified as ASA class 1 and 2, with 28 participants (56%) in class 1, 19 participants (38%) in class 2, and a small number, 3 participants (6%), in class 3. Among 50 patients, CapSure™ Permanent Fixation System was used in 16 patients, ProTack™ Fixation Device in 15 patients, and suturing with 2-0 polypropylene in 19 patients (Table 1).

|

Sl. No. |

Variable |

N (%) / M (SD) |

|

1 |

Mean age in years |

51.6 (10.8) |

|

2 |

Gender |

|

|

Male |

29 (58) |

|

|

Female |

21 (42) |

|

|

3 |

BMI |

28.8 (4.8) |

|

4 |

ASA class (no.of patients) |

|

|

1 |

28 (56) |

|

|

2 |

19 (38) |

|

|

3 |

3 (6) |

|

|

5 |

Mesh Fixation used |

16 (32) |

|

CapSure™ Permanent Fixation System (Group A) |

15 (30) |

|

|

ProTack™ Fixation Device (Group B) |

19 (38) |

|

|

Suturing with 2-0 polypropylene (Group C) |

|

Mesh Size and Defect Size Comparison

No statistically significant differences in mean mesh size were observed among the three mesh-fixation groups (Group A, Group B, and Group C) or in the overall comparison (p = 0.775). This suggests that the choice of mesh-fixation method did not significantly influence the size of the mesh used in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR). Similar to mesh size, there were no significant differences in mean defect size among the three groups or in the overall comparison (p = 0.79). This indicates that the mesh-fixation method did not appear to affect the initial defect size in patients undergoing LVHR (Table 2).

|

Characteri- stics |

Mesh-fixation group |

Overall (n = 50) |

P Value |

||

|

Group A |

Group B |

Group C |

|||

|

(n=16) |

(n=15) |

(n=19) |

|||

|

Mean Mesh size (cm) |

15.8 (2.9) |

16.4 (3.2) |

15.7 (2.9) |

15.9 (2.3) |

0.775 |

|

Mean defect size (cm) |

2.2 (0.6) |

2.8 (0.2) |

2.4 (0.4) |

2.6 (0.5) |

0.79 |

|

Mean No. of tacks per patient (SD) |

18 (1.2) |

18 (2.3) |

1 (0.5) |

12.3 (1.3) |

<0.001 |

|

Mean No. of trocars |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

0.32 |

|

Mean Operating time (min) |

40.5 (5.9) |

45.2 (10.2) |

55.9 (5.7) |

52.8 (10.9) |

<0.001 |

|

Mean Postoperative stay (days) |

1.5 (0.5) |

2.0 (0.2) |

1.0 (0.5) |

1.5 (0.7) |

<0.001 |

Tacks Used, Operating Time, and Postoperative Stay

There was a highly significant difference in the mean number of tacks used per patient among the three groups (p < 0.001). Groups A and B had an average of 18 tacks per patient, while Group C had a notably lower range (1-2 tacks). The mean operating time showed a significant difference among the three groups (p < 0.001). Group C had the longest mean operating time (55.9 minutes), followed by Group B (45.2 minutes) and Group A (40.5 minutes). This discrepancy suggests that the choice of mesh-fixation method may influence the overall duration of the surgical procedure. There was a significant difference in the mean postoperative stay among the three groups (p < 0.001). Group C had the shortest mean postoperative stay (1.0 day), followed by Group A (1.5 days) and Group B (2.0 days). This indicates that the potentially faster recovery compared to the other groups (Table 2).

Pain Scores and Quality of Life

Prior to the surgery, there were no significant differences in pain levels among the three groups. However, at both 2 weeks and 6 weeks postoperative, Group C exhibited significantly lower pain scores compared to Group A and Group B. This suggests that the chosen mesh-fixation technique in Group C may contribute to a more favourable early postoperative pain outcome. Interestingly, at the 3-month postoperative mark, the differences in pain scores diminished, and no statistically significant distinctions were observed among the groups. This could imply a convergence in pain levels as patients progressed further into the postoperative period. The analysis of postoperative scores (3 months) minus preoperative scores indicated no significant variation between the mesh-fixation groups. This finding suggests that, despite the divergent early postoperative pain experiences, the overall change in pain from preoperative to 3 months postoperative did not significantly differ among the groups (Table 3).

|

Assessment time |

Mesh-fixation group |

P Value |

||

|

Group A |

Group B |

Group C |

||

|

(n=16) |

(n=15) |

(n=19) |

||

|

Preoperative |

21.7 (20.4) |

20.1 (20.1) |

20.9 (20.3) |

0.41 |

|

2 weeks postoperative |

17.9 (19.8) |

21.4 (20.1) |

11.6 (9.1) |

<0.05 |

|

6 weeks postoperative |

8.7 (18.6) |

8.9 (16.7) |

6.4 (5.8) |

<0.05 |

|

3 months postoperative |

5.7 (12.6) |

6.7 (12.2) |

4.6 (9.5) |

0.4 |

|

Postoperative score (3 months) minus preoperative score (Mean difference with 95% CI) |

–16.0 (–21.2 to –8.3) |

–15.7 (–24 to –8.7) |

–16.3 (–21.6 to –10) |

0.9 |

Health-Related Quality of Life

The Table 4 presents pre and post values for various health concepts within the mesh-fixation groups (Group A, Group B, and Group C) along with their corresponding p-values. Among these concepts, physical functioning showed a statistically significant improvement from pre to post values in Group A (55.7 to 61.4) and Group C (41 to 55.9), with a p-value of 0.024. Conversely, role limitations due to physical problems did not exhibit significant differences across the groups (p = 0.96). However, role limitations due to emotional problems demonstrated significant improvement in Group C (36.1 to 64.7) compared to preoperative values, with a p-value of 0.018. Energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, social functioning, and general health did not show statistically significant differences in pre and post values across the mesh-fixation groups (p > 0.05). These findings suggest that while certain aspects of health, such as physical functioning and role limitations due to emotional problems, may be positively impacted by certain mesh-fixation techniques, other factors may not experience significant changes following laparoscopic ventral hernia repair.

|

Health concept |

Mesh-fixation group |

P Value |

|||||

|

Group A |

Group B |

Group C |

|||||

|

(n=16) |

(n=15) |

(n=19) |

|||||

|

Pre |

Post |

Pre |

Post |

Pre |

Post |

||

|

Physical functioning |

55.7 |

61.4 |

46 |

54.3 |

41 |

55.9 |

0.024 |

|

Role limitations due to physical problems |

62.5 |

83.4 |

47.3 |

60.7 |

43 |

53.3 |

0.96 |

|

Role limitations due to emotional problems |

59.8 |

44.4 |

34.3 |

40.83 |

36.1 |

64.7 |

0.018 |

|

Energy/fatigue |

55.9 |

51.9 |

41.5 |

47.3 |

42.7 |

59.4 |

0.3 |

|

Emotional well-being |

54.8 |

55.7 |

47.8 |

56.4 |

44.9 |

56.7 |

0.7 |

|

Social functioning |

56.5 |

59.2 |

39.5 |

51.6 |

42.5 |

59.1 |

0.2 |

|

General health |

55 |

38 |

25.6 |

35.3 |

37.5 |

56.5 |

0.73 |

Complications:

The Table 5 provides the incidence of various complications within the mesh-fixation groups (Group A, Group B, and Group C) along with their corresponding p-values. Regarding urinary retention, one case was reported in Group A (6.20%) and one in Group B (6.6%), while no cases were observed in Group C, with a p-value of 0.53. Prolonged ileus occurred in one patient in Group A (6.20%), one in Group B (6.6%), and two in Group C (10.5%), with a p-value of 0.87. The incidence of readmission to the hospital was minimal across all groups, with one case each in Group A (6.20%), Group B (6.6%), and Group C (5.2%), yielding a p-value of 0.98. For seroma formation, one case was observed in both Group A (6.20%) and Group B (6.6%), while no cases were reported in Group C, resulting in a p-value of 0.53. Similarly, hematomas were found in one patient each in Group A (6.20%) and Group B (6.6%), but none in Group C, with a p-value of 0.53. Notably, there were no incidences of bulging, pain requiring reoperation, or trocar hernia observed in any of the mesh-fixation groups. These findings indicate a generally low occurrence of postoperative complications across all groups, with no significant differences detected among them.

|

Complication |

Mesh-fixation group |

P Value |

||

|

Group A |

Group B |

Group C |

||

|

(n=16) |

(n=15) |

(n=19) |

||

|

Urinary retention- |

|

|

|

0.53 |

|

Yes |

1 (6.20) |

1 (6.6) |

0 |

|

|

No |

15 (93.75) |

14 (93.3) |

19 (100) |

|

|

Prolonged ileus- |

|

|

|

0.87 |

|

Yes |

1 (6.20) |

1 (6.6) |

2 |

|

|

No |

15 (93.75) |

14 (93.3) |

17 (89.4) |

|

|

Readmission to hospital- |

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

1 (6.20) |

1 (6.6) |

1 (5.2) |

0.98 |

|

No |

15 (93.75) |

14 (93.3) |

18 (94.7) |

|

|

Seroma |

|

|

|

0.53 |

|

Yes |

1 (6.20) |

1 (6.6) |

0 |

|

|

No |

15 (93.75) |

14 (93.3) |

19 (100) |

|

|

Hematoma- |

|

|

|

0.53 |

|

Yes |

1 (6.20) |

1 (6.6) |

0 |

|

|

No |

15 (93.75) |

14 (93.3) |

19 (100) |

|

|

Bulging

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

|

Pain requiring reoperation

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

|

Trocar hernia

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

Discussion

Comparing the findings of the current study with previously published articles in the field of laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR) provides valuable insights into the consistency and variability of results across different investigations 2, 5, 6 . Several aspects, including patient demographics, surgical characteristics, and postoperative outcomes, were explored in the context of mesh-fixation methods.

During the early postoperative (PO) period, the persistence of pain is a notable concern, leading to an increased reliance on pain medications, delayed bowel function, and prolonged hospital stays. 10, 11 Studies on laparoscopic incisional hernia repair have reported a chronic pain incidence ranging from 1% to 3%. 1, 2 Various investigations into PO pain after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair, including those by Leblanc and Booth in 1993, focused on the controversial topic of mesh fixation techniques. Initially LeBlanc utilized transfacial suture (TS) and titanium tack in operations. 12 However, the emergence of chronic pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic ventral hernia repair prompted further exploration of fixation methods.

Numerous studies, such as those by researchers employing transfacial suture (TS) or tack fixation, found no significant difference in terms of pain and recurrence outcomes. 13, 14, 15 Over time, the search for alternative fixation methods led to the use of fibrin sealants and absorbable tacks by some investigators. 16 While absorbable fixation devices were developed to provide sufficient tensile fixation strength with acceptable PO pain compared to traditional nonabsorbable devices, the debate over the optimal mesh fixation technique in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair continues. In the current study, the suture group had significantly lower pain in postoperative week 2 compared to the other groups.

Contrary to some earlier studies that reported significant differences in mean mesh size among different fixation techniques, our study did not find such distinctions. 17 This aligns with the findings by Elsayed ME et al., who also reported no significant impact of mesh-fixation methods on mesh size in their respective investigations. 18 The consistency in these results suggests that the choice of mesh-fixation may not be a critical determinant of mesh dimensions in LVHR, corroborating the notion that variations in surgical technique may not necessarily translate into differences in mesh-related parameters.

The significant differences in mean operating time and postoperative stay observed in our study align with the results reported by Rasul S et al., 10 These studies also found variations in surgical duration and length of hospital stay associated with different mesh-fixation methods. However, the specific factors contributing to these differences warrant further investigation, as our study did not delve into the detailed operative steps that my influence these outcomes.

The study's findings regarding postoperative pain outcomes at 2 weeks and 6 weeks align with the results reported by Shankaran R et al., who observed differences in early postoperative pain based on mesh-fixation methods. 19 However, the convergence of pain scores at the 3-month postoperative mark, as seen in our study, is consistent with the findings of Silfvenius AU et al. and suggests that the impact of fixation techniques on pain may be more pronounced in the immediate postoperative period. 20

The assessment of health-related quality of life using the SF 36-item Short-Form Health Survey revealed differences in physical functioning and role limitations due to emotional problems among mesh-fixation groups, consistent with the findings of Wassenaar E et al. 21

Firstly, the sample size in each mesh-fixation group was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. A larger sample size would provide more robust statistical power and allow for more reliable conclusions. Furthermore, the follow-up period was limited to 3 months postoperatively, which may not capture long-term outcomes and complications associated with mesh fixation methods. The observational nature of the study also restricted the scope of generalizability. Addressing these limitations in future randomized controlled studies would enhance the validity and applicability of the findings.

Conclusion

Our study investigated various aspects of laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR) with different mesh-fixation techniques. The analysis revealed no significant differences in mean mesh size or defect size among the groups, indicating that mesh-fixation methods were not influenced by these parameters. However, significant variations were observed in the mean number of tacks used per patient, operating time, and postoperative stay, suggesting an impact of mesh-fixation techniques on surgical outcomes and recovery duration. Pain scores showed early differences but converged over time, while health-related quality of life outcomes demonstrated improvements in certain domains, particularly physical functioning, and role limitations due to emotional problems, with variations across the mesh-fixation groups. Furthermore, the incidence of complications was generally low across all groups, with no significant differences detected among them. These findings underscore the importance of considering mesh-fixation methods in LVHR to optimize surgical outcomes and patient recovery. Further research with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods is warranted to validate these findings and inform clinical practice effectively.