Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2020.v06i02.001

Year: 2020, Volume: 6, Issue: 2, Pages: 1-7

Review Article

Kartik Kashyap1, Ravish Thunga2

1Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, The Oxford Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India,

2Professor, Department of Psychiatry, A. J. Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Kartik Kashyap Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, The Oxford Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. Phone: +91-9449837882. E-mail: [email protected]

Introduction: Studies have commonly suggested depression to be the most common diagnosis among people attempting suicide. Recent life events were found to be significant risk factors which were universal across countries and cultures. Although life stressors have been described in the causation of depression and suicidal behavior, the exact nature of the relationship is still unclear, and hence needed to be studied more closely.

Aims and objectives: The aims of the study were as follows (1) to examine the severity of depression in individuals who attempted suicide/intentional self-harm (ISH), (2) to examine the nature and pattern of life events in patients who attempted suicide/ISH, (3) to evaluate the relationship between depression and suicidal intent, and (4) to evaluate the relationship between stressful life events and suicidal intent.

Materials and Methods: Seventy-five consecutive referrals of attempted suicide (ISH), aged 15 years and above, were examined for the severity of depression, nature and pattern of life events, relationship between depression and suicidal intent, and between stressful life events and suicidal intent. The scales used were a sociodemographic profile, MINI Plus 5.0, beck’s depression inventory (BDI), suicide intent scale (SIS), and presumptive stressful life events scale (PSLES).

Results and Discussion: Mood disorders were common diagnoses. The presence of Life events was commonly noted, 46.7% had PSLES score of >150 life change units. Interpersonal conflicts, failure in love, unemployment, and financial difficulties were common stressors. The mean BDI score of the sample was 17.94 ± 11.46. The mean SIS score was 11.81 ± 7.06; 20% showed low intent, 21.3% had a medium intent, and 58.7% had high intent. The SIS scores showed a significant correlation with PSLES scores. Marital status did not show any statistical significance with suicidal intent. The relationship of marital status with suicidal intent is still not clear and needs a closer look in future studies.

Conclusion: The occurrence of major life events has been known to indicate a period of increased risk when supportive interventions could prevent the evolution of distress to a suicide attempt. An attempt of suicide, along with a PSLES score of more than 150, forms a high-risk group for crisis intervention/suicide prevention.

KEY WORDS:Attempted suicide, depression, intentional self-harm, stressful life events, stressors, suicidal intent, suicide.

Self-harm is attempted by individuals in the productive years, especially in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life, and several socioeconomic stressors contribute heavily in the development of psychiatric disorders, particularly depression and suicide. Some of the risk factors for suicidal behavior are being unmarried, divorced, separated, widowed,[1] as well as living alone, or being isolated from family and social networks.

Studies have commonly suggested depression to be the most common diagnosis among people attempting suicide, accounting for nearly 35–79% of all attempters.[2] Rao[3] felt that a depressive mood serves as a “final common pathway” for suicidal behavior. Studies have also found a correlation between the severity of depression and suicidal intent.[4] However, others[5] opined that suicide is not simply due to “depression” and implicated factors such as social isolation, early parental loss, and loss or threat of loss of an important relationship.

Various scales have been designed to assess the impact of life stressors[6,7] and to show the association between the onset of psychiatric illness and life events.[8,9]

The degree of distress the life events cause, as well as the role of a major event not under the control of the patient, just before the onset of the psychiatric illness, has been emphasized in the causation of psychiatric illness.[6,10-12] “Bereavement (parents/ spouses/significant others),” “occupation (job problems, unemployment),” and “family and social relationship” were prominent life events. Studies have found that suicide risk factors included interpersonal conflict, marital disharmony with spouse, failure in love, unemployment, sudden economic bankruptcy, domestic violence, and the presence of stressful life events in the past 6 months.[13-15] Recent life events were found to be significant risk factors[16] which were universal across countries and cultures.[17] Earlier studies[18] tried to correlate life stress, general health questionnaire (GHQ) scores, and suicidal intent and found that both subscales of the Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) correlated with GHQ score and total life stress experienced in the previous 6 months. The authors concluded that the relationship is very complex and that the impact of life stress is mediated through other psychological variables.

Although life stressors have been described in the causation of depression and suicidal behavior, the exact nature of the relationship is still unclear, and hence needed to be studied more closely.

Aims and objectives

The aims of the study were to as follows:

The study was conducted at Wenlock District Hospital, which is the main Government Hospital at Mangalore, South India and Kasturba Medical College Hospital, Mangalore. Both hospitals have a 100% admission rule for all cases of self-harm.

This is to ensure thorough observation for physical complications, and also for psychosocial evaluation and counseling, which occurs concurrently during the period of admission. This was a cross-sectional study of 75 consecutive referrals of attempted suicide referred to Wenlock District Hospital and Kasturba Medical College Hospital, Mangalore. The sampling method is a non-random sampling (convenient sampling).

Inclusion criteria

The following criteria were included in the study:

Exclusion criteria

The following criteria were excluded from the study:

The study got clearance from the Ethics Committee of Kasturba Medical College and Hospital. The patients voluntarily consented on the informed consent form after all the study-related procedures/ assessments and confidentiality was explained to them. Not consenting to the study did not, in any way, affect their further treatment.

The assessment was done as early as possible during the hospital stay. Patients who were physically unstable or were disoriented immediately after the attempt were approached again once their physical status and cognitive deficits improved. For every patient, the effort was made to interview a key informant/relative, at least over the telephone.

Definitions

For the purpose of the study, the definition of self-harm was adopted from Hawton et al.[19] to minimize bias and ensure maximum coverage. Self-poisoning is defined as the intentional self- administration of more than the prescribed dose of any drug, whether or not there is evidence that the act was intended to result in death. Self-injury is defined as any injury which has been deliberately self-inflicted.

Instruments used

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 16 (SPSS 16.0) for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL); confidence interval of 95%, P = 0.05.

Of the total sample of 75 attempters (41 males and 34 females), 38 (50.6%) were single and unmarried; divorced /widowed accounted for 2.7%. Two of the attempters (2.7%) were living separately, though not legally divorced. Thirty three (44%) were married and living with a spouse.

Among the people with a psychiatric diagnosis, 36% had a mood/affective disorder, principally, dysthymia, and depressive episode. The group of adjustment disorders accounted for 26.7%. Other diagnoses are discussed in a different companion paper.[23]

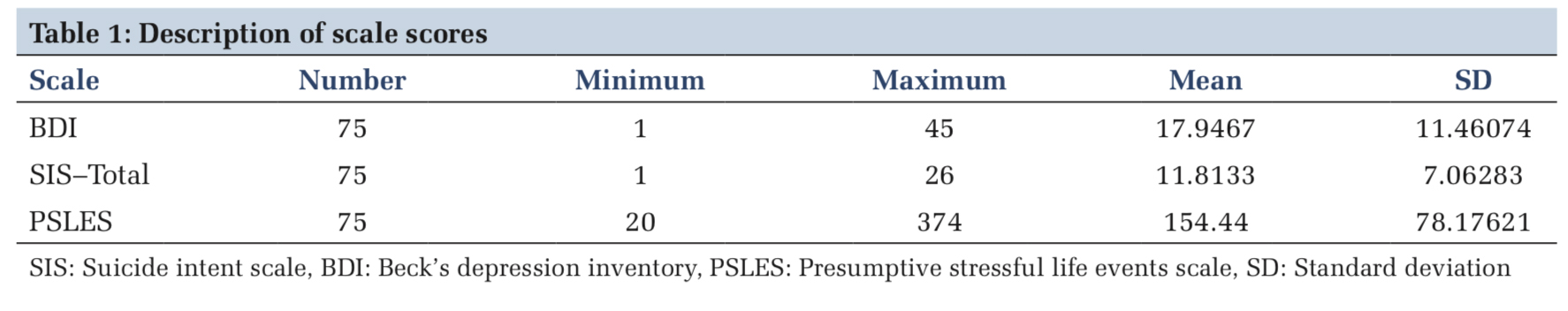

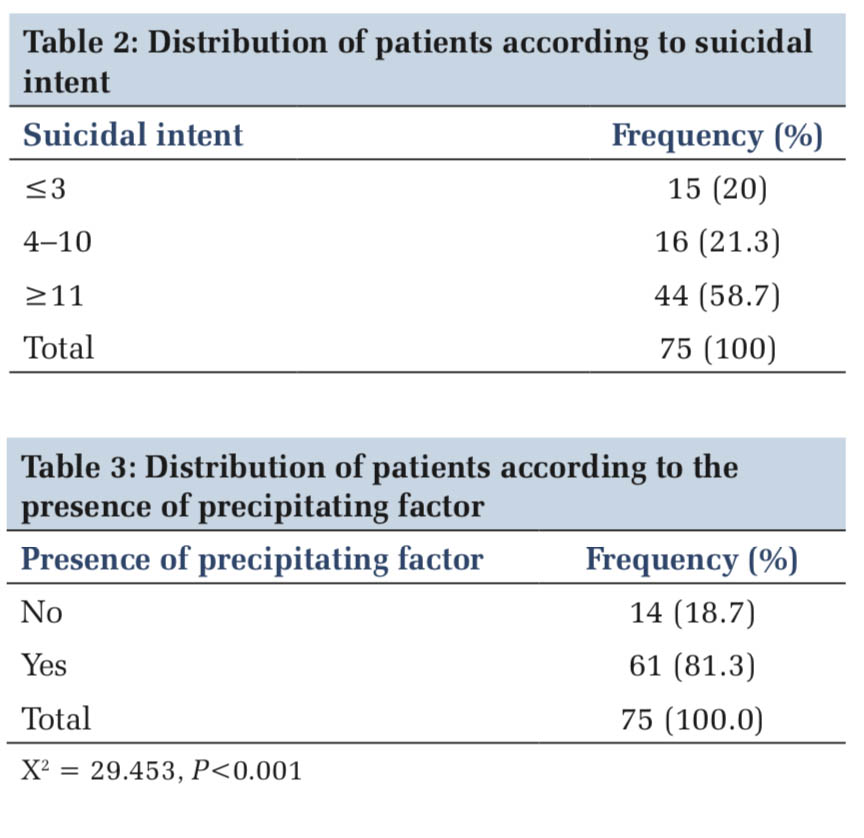

Table 1 shows that the mean BDI score of the sample was 17.94 ± 11.46, with a minimum of 1 and a max of 45. The mean SIS score was 11.81 ± 7.06, with a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 26. 15 subjects (20%) scored less than 3, showing low intent, 21.3% had a medium intent, with SIS score 4–10, and 58.7% had high intent (SIS score more than or equal to 11) (Table 2).

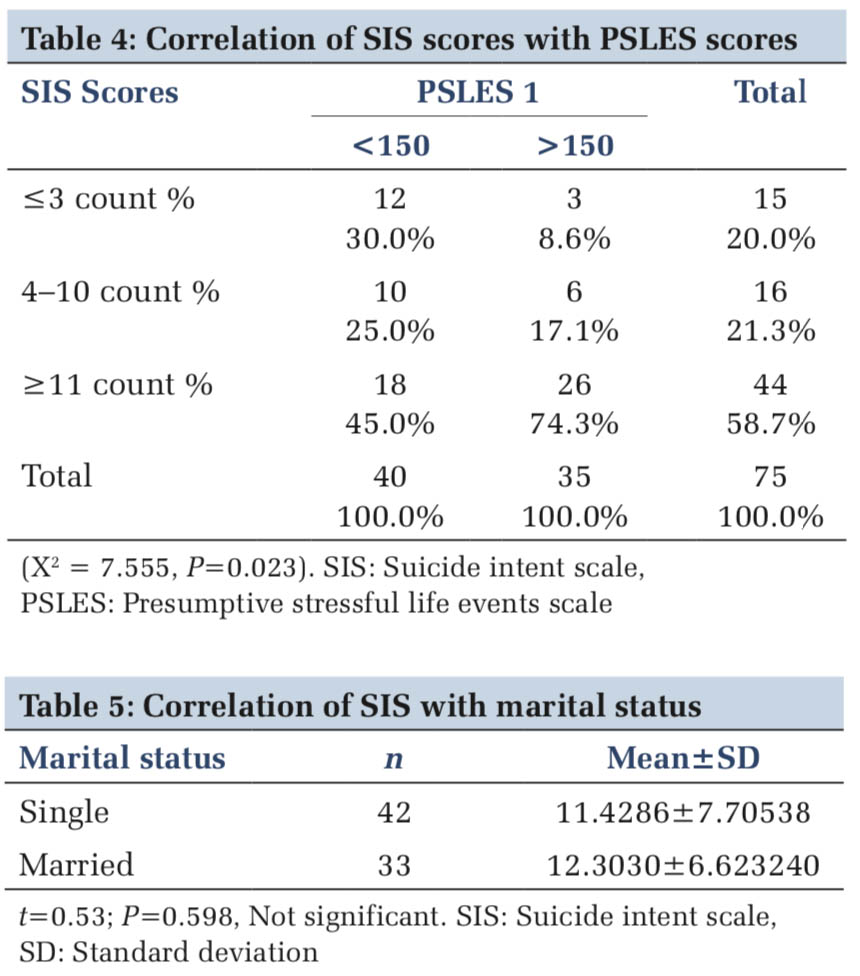

Fourteen (18.7%) of the 75 attempters did not have any precipitating factor/stressor before the event. Of the remaining, 39 (52%) had an acute precipitating event and 22 (29.3%) had ongoing stressors (Figure 1). Interpersonal conflicts, failure in love, unemployment, and financial difficulties were the main stressors noted in our study. Change of residence was also commonly noted.

The presence of a precipitating factor/stressor for the attempt was very highly significant (Table 3), with P < 0.001. The SIS scores showed a significant correlation with PSLES scores, with a Life Change Unit cutoff of 150 (X2 = 7.555, P = 0.023) (Table 4).

When the SIS total score was correlated with the marital status, using Student’s unpaired t-test (Table 5), we did not find any significant difference between the single and the married groups (t = 0.53; P = 0.598 ).

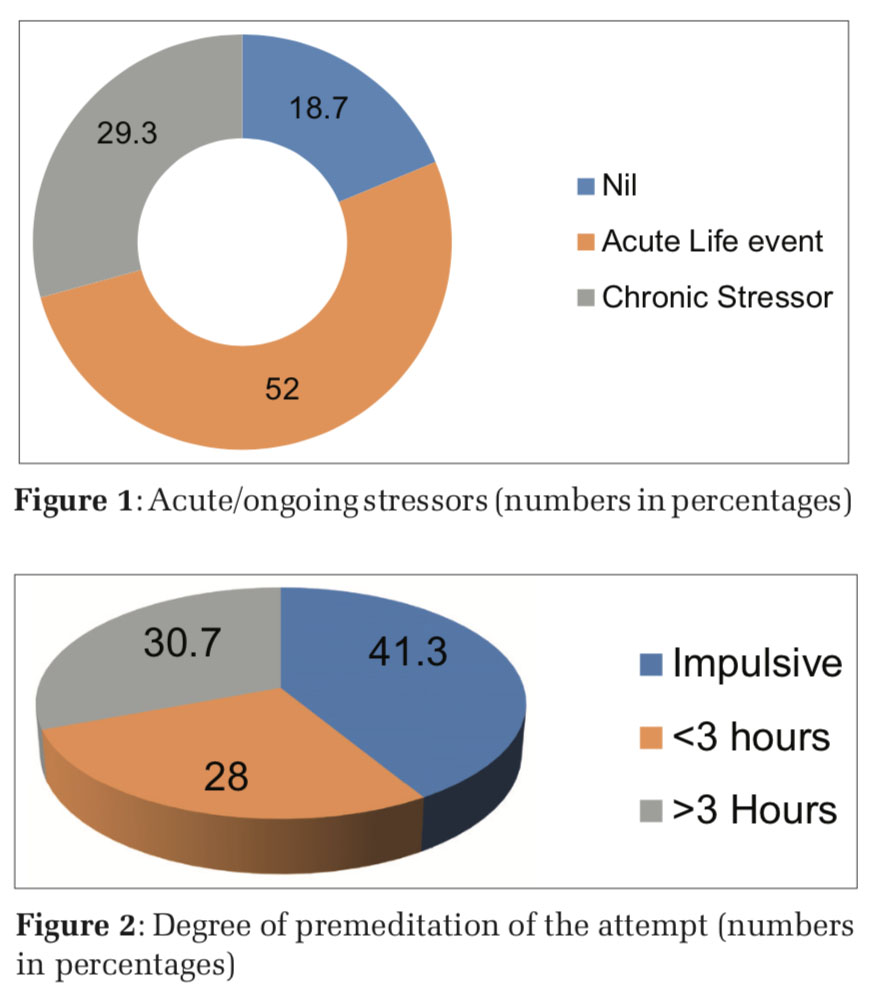

Figure 2 shows the degree of premeditation of the attempt, as per question 15 of SIS. About 41.3% attempted suicide impulsively, 28% contemplated suicide for 3 h or less before the attempt, while 30.7% had contemplated suicide for more than 3 h before the attempt.

With a view to correlate impulsivity with low depressive scores, the degree of premeditation was compared with the BDI, using the Kruskal Wallis test (Table 6). This showed a very highly significant difference with higher premeditation correlating with higher BDI scores (P = 0.001). On average, persons who had contemplated suicide for more than 3 h showed a mean BDI score of 27.78 ± 10.65.

Using the SIS’s question on alcohol/substance use, it was found that 74.7% did not take any substance before the act; 5.3% took alcohol/other substances deliberately to facilitate the implementation of the attempt. In the remaining 20% of the subjects, alcohol/other substance was still an important factor which could impair judgment.

Seeking to find a correlation between impulsive suicidal attempt and substance use at the time of ISH, we compared the degree of premeditation and the relation of substance use at the time of the ISH. However, we did not find a significant correlation between impulsive ISH and substance use at the time of ISH.

With a view to correlate impulsivity with low depressive scores, the degree of premeditation was compared with the BDI, using the Kruskal Wallis test (Table 6). This showed a very highly significant difference with higher premeditation correlating with higher BDI scores (P = 0.001). On average, persons who had contemplated suicide for more than 3 h showed a mean BDI score of 27.78 ± 10.65.

Earlier studies[1,2,24,25] report single (unmarried/ widowed/divorced/separated) marital status being at higher risk for suicide. Rao’s study[3] had a high preponderance (61.9%) of married people, while in another study by same author, 47 were married and 59 were single in a sample of 114. Lal and Sethi[26] observed that it is the married individual, regardless of sex, who is more likely to indulge in a suicidal act, bowing to all the stresses of maintaining a family, financial being the chief stressor. In the West, marriage is generally protective against suicide; divorced, separated, widowed, and single people are more likely to commit suicide than married people. Persons living alone are at particular risk.[27] However, the WHO World report reveals that marriage is not a strong protective factor for suicide attempts in developing countries.[28] On similar lines, we did not find a significant difference between the unmarried and the married groups. The relationship of marital status with suicidal intent is still not clear and needs a closer look in future studies. Is it that the Indian society has other suicide counters for the unmarried in the form of a well-knit circle of friends and family who rally around the patient, and offer social support, is a major question that needs more light. Myers[29] found a significant number of female attempters to be having a “poor quality marriage.” If this is true, further studies on suicide need to correlate marital satisfaction with suicidal intent. A review of Indian studies[30] proposed that the quality of the marital relationship, extended family support, and ability to handle stresses related to marriage and child-rearing were more important than marital status, per se. However, they also noted that these were difficult to study.

Heikkinen et al.,[16] while reviewing earlier studies, had noted interpersonal losses and conflicts, financial trouble, job problems, and somatic illnesses to be the most common life events among suicides. He also noted interpersonal events to be especially common during the last few weeks of life. We found the presence of stressors in 81.3% of our sample – 52% had an acute life event, while 29.3% had ongoing stressors. Other Indian studies[31,32] had reported around 50–55% having acute stressors and said in the remainder, there could be chronic, ongoing stressors. In our study, the presence of a precipitating factor/stressor for the attempt was very highly significant, and 46.7% had a PSLES score of >150 life change units. The SIS scores showed a significant correlation with PSLES scores. Interpersonal conflicts, failure in love, unemployment, and financial difficulties were the main stressors noted in our study. This is similar to earlier studies,[13-15] where interpersonal conflicts, marital disharmony with a spouse, failure in love, unemployment, and sudden economic bankruptcy were the major stressors. A recent review of Indian research also emphasized that marital conflict among women and interpersonal conflict among men[30] were important risk factors. A recent change of residence was reasonably common in our study. This is very important in terms of social support because the change in residence/occupation may dissipate the social network systems.

Regarding premeditation of the attempt, we found 41.3% attempted suicide impulsively, 28% contemplated suicide for 3 h or less before the attempt, while 30.7% had contemplated suicide for more than 3 h before the attempt. An Indian study[33] had found a predominant number of attempters having more than 3 h of premeditation, but their sample size of 13 requires replication with a larger sample.

Earlier studies had suggested depression to be the most common diagnosis among people attempting suicide. Some authors[3] had felt that a depressive mood serves as a “final common pathway” for suicidal behavior; others[5] opined that suicide is not simply due to “depression” and implicated other factors. Studies had noted a correlation between the severity of depression and suicidal intent.[4] In our own study, a very highly significant difference was noted between depressive scores and premeditation. Higher suicidal contemplation showed higher BDI scores, indicating that the severity of depression is an important factor when trying to assess individuals who are more at risk for attempting suicide.

Alcoholism and suicide have been interlinked, with high rates of either illness seen in the other.[30] Alcohol had played an important role in almost 25% of the subjects in our study, while in some it impaired judgment, in others, alcohol was deliberately ingested to facilitate the attempt. This group can be referred to as a special group where intervention is highly possible. Ideators who are using alcohol to make courage for the attempt can be assessed at the primary care level for mood symptoms and suicidal intent and referred for counseling at a higher level. Alcohol abusers who have ingested enough alcohol to impair judgment also require psychoeducation and if needed, counseling for deaddiction and suicidal intent.

It is well known that social stresses can lead to suicide.[16] The occurrence of major life events has been known to indicate a period of increased risk[30] when supportive interventions could prevent the evolution of distress to a suicide attempt.[34] An attempt of suicide, along with a PSLES score of more than 150, forms a high-risk group for crisis intervention/suicide prevention.

Strengths of the current study

This has been a well-structured study using well- validated scales to evaluate for depression before the act, life events, and suicide intent. Any form of self-harm/self-poisoning, regardless of motivation, has been included. Physically, ill/patients with tracheostomy/cognitive deficits were approached again, when they were better. A hospital practice of admitting all patients with self-harm and a well- functioning referral system ensured that patients were usually not missed.

Limitations of the current study

This was a cross-sectional study. A prospective follow-up study to evaluate any repeat attempts of self-harm and psychiatric morbidity would have been more helpful. This study was done in patients approaching the hospital with an attempt of self-harm. There is a need to replicate the study in community samples. There is a possibility of some patients of attempted suicide/self-harm being missed due to inadequate reporting/patients seeking treatment elsewhere.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.