Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2021.v07i01.011

Year: 2021, Volume: 7, Issue: 1, Pages: 64-67

Original Article

Shivaprasad Gouda1, Ambresh Badad2, Ashok Hogade3

1Senior Resident, Department of Dermatology Venereology and Leprosy, Mahadevappa Rampure Medical College, Gulbarga, Karnataka, India,

2Associate Professor, Department of Dermatology Venereology and Leprosy, Mahadevappa Rampure Medical College, Gulbarga, Karnataka, India,

3Professor and HOD, Department of Dermatology Venereology and Leprosy, Mahadevappa Rampure Medical College, Gulbarga, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Ambresh Badad, Associate Professor, Department of Dermatology Venereology and Leprosy, Mahadevappa Rampure Medical College, Gulbarga, Karnataka, India. Phone: +91-9538476038. E-mail: [email protected]

Background: Acneiform eruptions represent 1% of all drug-induced skin reactions following exposure to drugs such as hormones, vitamins, halogens, anti-tubercular drugs, neuropsychotherapeutic drugs, immunomodulating agents, and other miscellaneous drugs.

Aim: The aim of the study was to identify the topical, inhalational, intralesional, and systemic drugs causing acneiform eruptions.

Materials and Methods A total of 46 patients presenting with acneiform eruptions were studied with detailed drug history.

Conclusions: Acneiform eruption is a relatively common and often misdiagnosed entity. Systemic steroids are the most common cause of acneiform eruption.

KEY WORDS: Acneiform eruptions, Adverse drug reaction, cutaneous drug reactions

Drug-induced acneiform eruptions are inflammatory follicular reactions resembling acne vulgaris but generally lack comedones, presenting clinically as monomorphic papules or pustules over the face, chest upper back, and arms.

The criteria that determine acneiform eruptions are:

All the consented patients having acneiform eruptions presenting to Skin and V.D. outpatient department (OPD) and patients referred from other departments OPD over a period of 6 months.

Methodology:

After taking the patient’s written consent, patients were diagnosed based on history and clinical features. Details were noted according to a pre- planned questionnaire. It included age, gender, qualification, type of drugs used, dose and duration of application, source of prescription, and indication, whereas in treatment patient was advised to stop the causative drug but a decision needs to be balanced against the drug indication and/or if any alternative agents are available.

A total of 46 patients were included in the study, out of which 13% (n = 6) were females and 87% (n = 40) were males. The age of the patients in our study varied from 16 to 70 years. The maximum number of patients (n = 36) were from the age group of 30–50 years, followed by (n = 6) patients in the group of 50–70 years and (n = 4) patients in the age group of 10–30 years. The youngest patient was a 16-year-old and the oldest was 70 years old.

About 76% of the patients (n = 35) belonged to rural areas and 24% (n = 11) from urban areas.

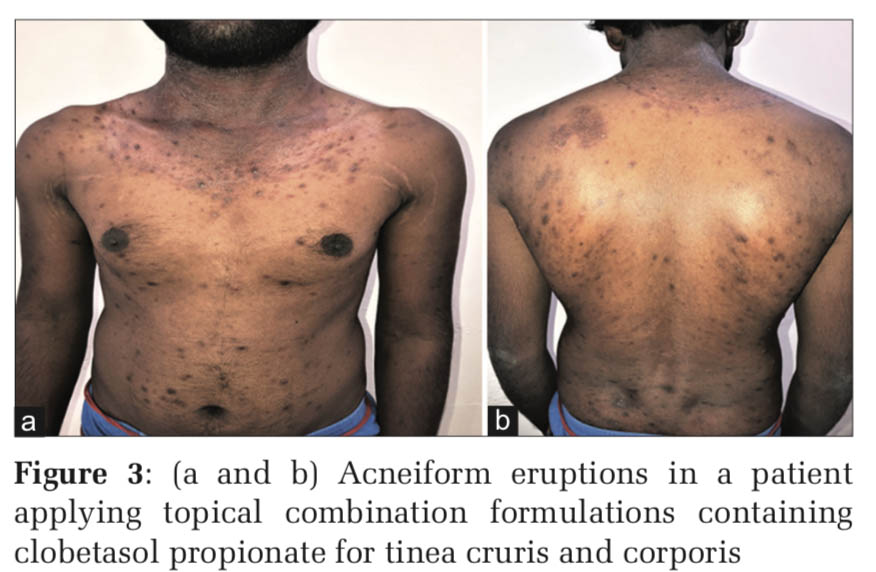

The majority 54.3% (n = 25) of the patients were uneducated and the majority 60.8% (n = 28) of the implicated drugs were not indicated for the disease (e.g., topical steroid combination formulations and systemic steroid for tinea infections).

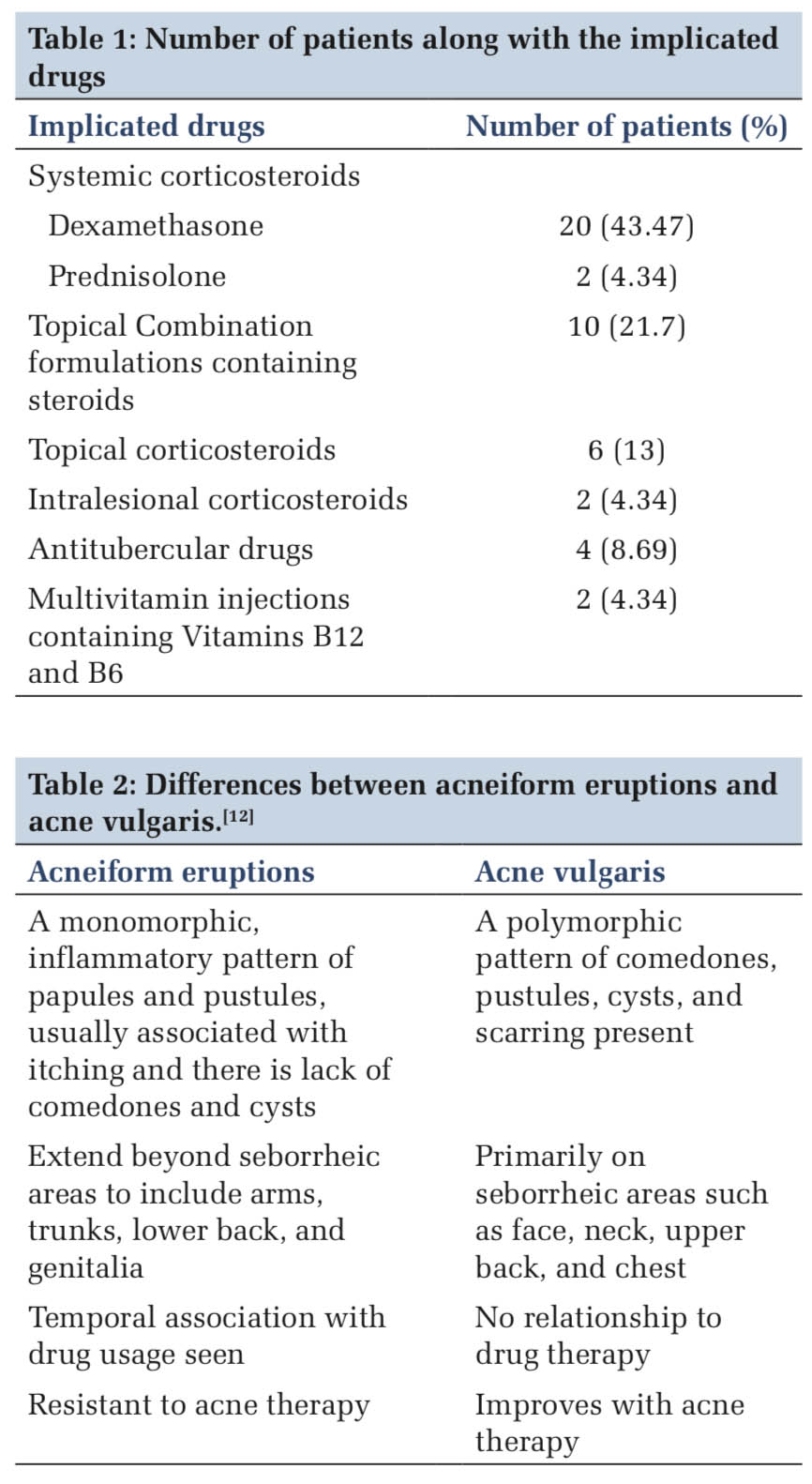

In our study, The drugs which are implicated to cause acneiform eruptions and their frequency is given in Table 1.

Acneiform eruptions are not hypersensitivity reactions. Pathological mechanisms and variation in the histopathology of drug-induced acneiform eruptions depends on the underlying drug. A drug- induced acneiform eruption is to be suspected in patients if the onset of acne is sudden and abrupt in the absence of a history of acne vulgaris or unusually severe acne flare in a patient with a past history of mild acne vulgaris, or acne developing at an unusual age of onset.

The latency between drug initiation and the onset of acne varies with different type of drugs. Shorter latency of 1 month or less has been reported with systemic corticosteroids, androgens, and Vitamin B; latency of greater than 1 month are usually observed with ciclosporin, tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), lithium, anti-epileptics, and anti-tuberculosis treatment.[1]

Steroid-induced acneiform eruptions

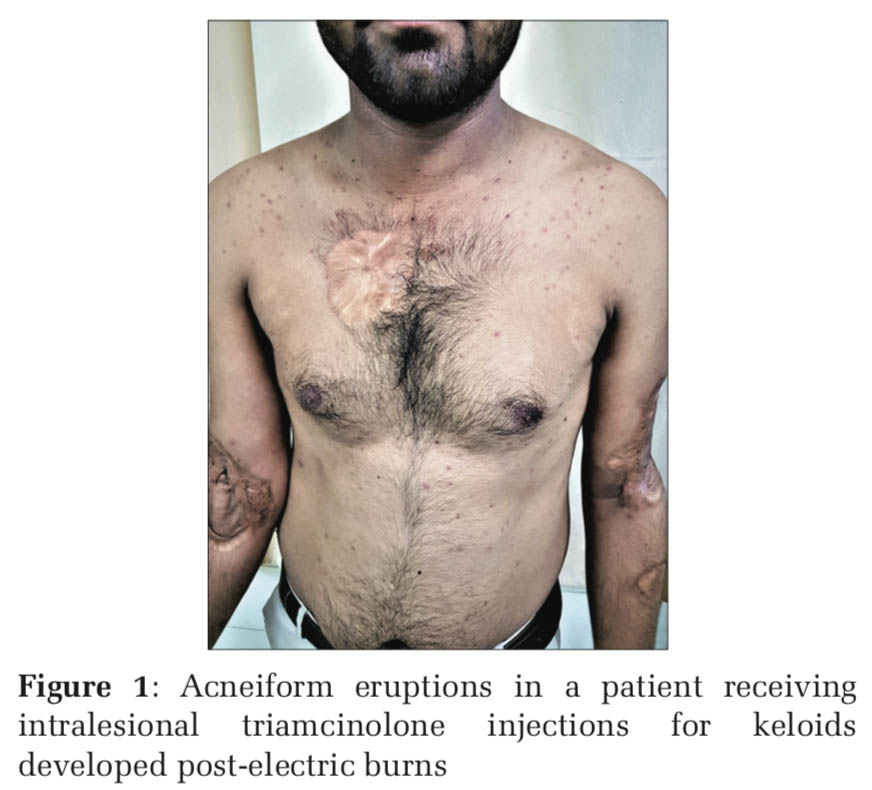

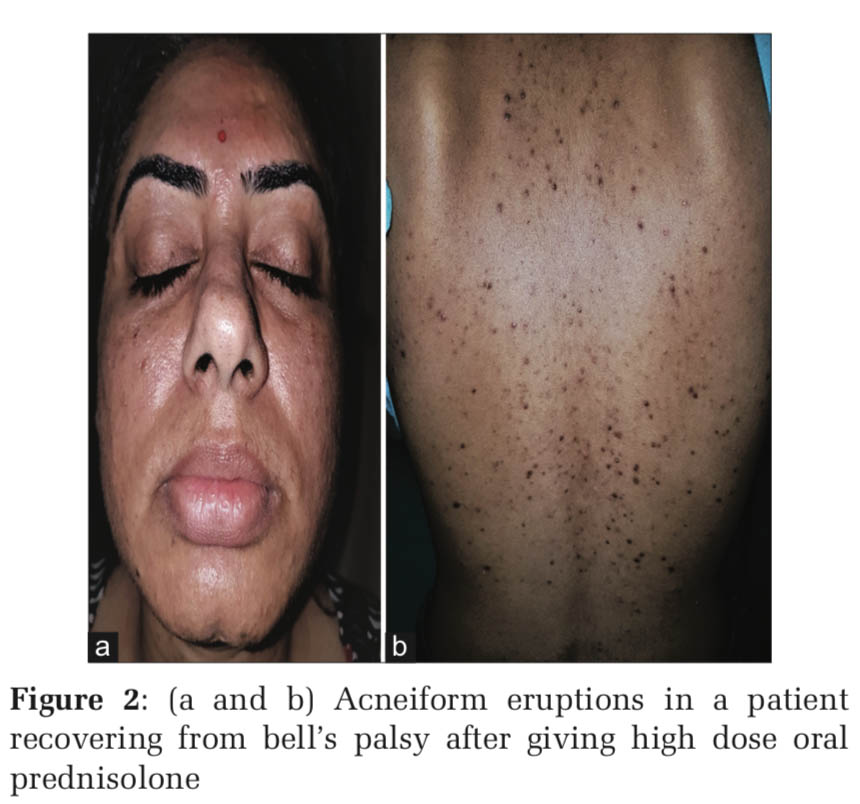

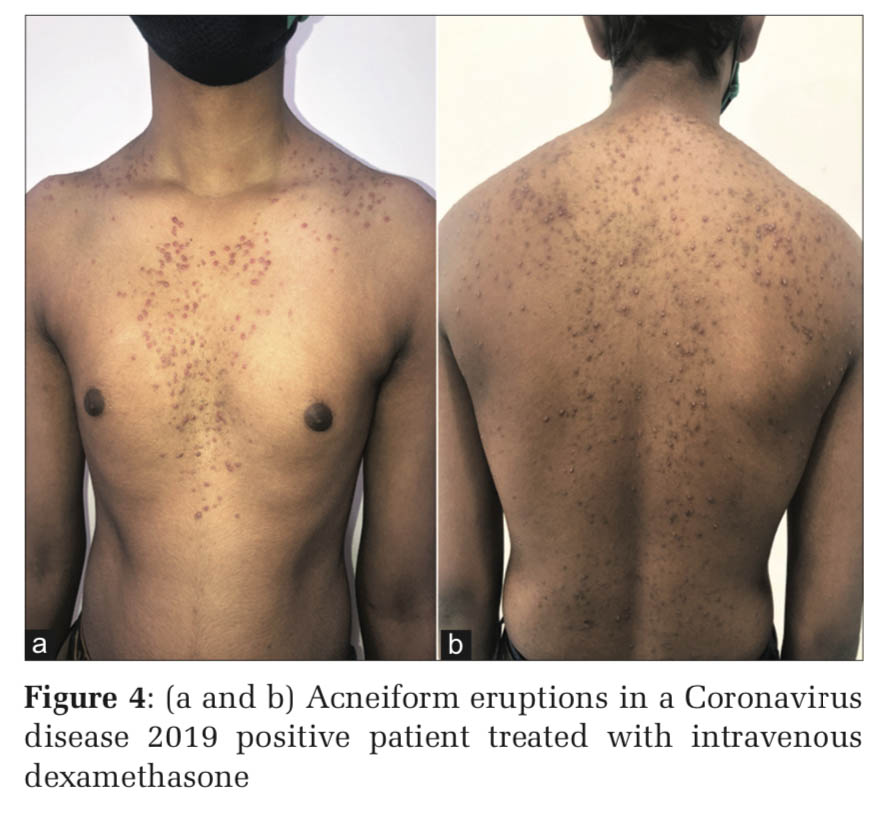

Upregulation of toll-like receptor-2 has been reported in human keratinocytes treated with glucocorticoids and this explains why corticosteroid-induced acne consists of predominantly inflammatory lesions of papules and pustules, whereas androgenic hormones and hormonal contraceptives containing progestogens with androgenic activity cause follicular keratinocyte proliferation and an increase in sebum production (Figures 1-4).[1]

Antitubercular drugs induced acneiform eruptions

Isoniazid or rifampicin induced eruptions are mild and less common. A probable explanation is due to isoniazid’s structural analog to niacin molecule and its competitive inhibition predisposes some patients to follicular hyperkeratosis. No explanation is available for rifampicin-induced eruptions.[2]

Lithium induced acneiform eruptions

Lithium is used to treat bipolar disorders. Acneiform and psoriasiform eruptions are the commonest cutaneous reactions. Lithium is associated with follicular hyperkeratosis and increased neutrophilic chemotaxis but how these reactions occur is still not completely clear.[3]

TCA induced acneiform eruptions

TCA causes the onset of monomorphic microcysts, the lesion can occur many months or years after initiation of treatment and severity depends on the dosage and duration of therapy. TCA increases the keratinization and may lead to necrosis of eccrine glands.[4]

Antiepileptics induced acneiform eruptions

Phenytoin, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, and valproate are the common causative agents but the pathogenesis is not completely understood.[5-7]

Vitamins induced acneiform eruptions

High doses of Vitamin B6 and Vitamin B12 have known to cause facial acneiform eruptions, likely cause being the use of iodine for vitamin extraction, which induces hyperkeratinization.[8]

Immunomodulating drugs induced acneiform eruptions

Sirolimus – an immunosuppressive drug often used after organ transplantation, it has a direct toxic effect on hair follicles and alteration of epidermal growth factor.[9]

Cyclosporine – The drug causes eruptions by modifying the structure, function of the pilosebaceous units.[10]

Halogenated hydrocarbons induced acneiform eruptions It’s hypothesized that these compounds are eliminated by sebaceous glands which lead to hyperkeratosis and neutrophil stimulation in follicles. It can even occur due to exposure to fumes produced during the manufacturing of chlorine and it is by-products like dioxin leading to chloracne. Lubricating oils, crude coal, thyroid medications, cough expectorants, radiocontrast dyes, vitamin, and mineral supplements are also lesser known causes of acneiform eruptions.[11]

Dapsone induced acneiform eruptions

Commonly used for treating leprosy, dermatitis herpetiformis, and seldomly used to treat acne vulgaris but paradoxically can cause acneiform eruptions.[12]

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors induced acneiform eruptions

PRIDE complex, that is, “Papulopustules and/or paronychia, regulatory abnormalities of hair growth, itching, and dryness due to EGFR inhibitors” is the collection of symptoms known to be associated. The pathogenesis is unclear but histologically lesions display neutrophilic folliculitis.[12]

Acneiform eruptions are often misdiagnosed for acne vulgaris or Gram-negative folliculitis. As there are no specific diagnostic criteria, differentiating features between drugs induced acneiform eruption and acne vulgaris are helpful [Table 2].

The National Cancer Institute has given a widely used severity grading scale which not only classifies the severity of acneiform eruptions but also helps in deciding the line of management [Table 3].

A trial of drug termination should be tried if multiple drugs are implicated. Drugs that were started within 1–2 weeks before onset of initial eruption should be suspected first. If drug termination is not possible, then topical benzoyl peroxide, hydrocortisone 1% cream, fluocinonide 0.05% cream are considered in Grades 1 and 2 cases. Additional to topical treatment, systemic doxycycline 100 mg twice along low dose isotretinoin 20–30 mg daily is considered in Grade 3 cases and additional to topical medications Intravenous antibiotics are added in Grade 4 cases.

Non-ablative fractional laser is found to be effective in treating recalcitrant cases.

Acneiform eruption is a relatively common and often misdiagnosed entity. Diagnosis of acneiform eruption must be considered when a patient on multiple drugs presents with sudden onset of monomorphic eruptions resembling acne vulgaris. The majority of cases (87%) were due to corticosteroids and most of the cases are due to misuse by both the prescribing doctors and the patients themselves because it gives instant relief to most of the signs and symptoms.d upon to do so.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.