Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2016.v02i03.005

Year: 2016, Volume: 2, Issue: 3, Pages: 25-29

Original Article

K Geeta Avadhani1 , Arun Kumar Shirshetty2

1Professor and Unit Chief, Department of General Surgery, Adichunchanagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, Mandya, Karnataka, India,

2PG Resident, Department of General Surgery, Adichunchanagiri Institute of Medical

Sciences, Mandya, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Arun Kumar Shirshetty, Department of General Surgery, Adichunchanagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, BG Nagar, Nagamangala, Mandya, Karnataka - 571 448, India. Phone: +91-9739459214. E-mail: [email protected]

Introduction: Acute pancreatitis is a common surgical emergency. Alcohol abuse and biliary tract diseases are etiological in the majority of the cases. The diagnosis is made by clinical examination which is supported by laboratory investigations and imaging studies. Most of the acute pancreatitis are of mild to moderate severity and have good prognosis. The aim of our study is to evaluate the pattern of acute pancreatitis in the rural population and compare the role of serum amylase/lipase as diagnostic tool along with imaging studies and clinical examination.

Materials and Methods: This was a prospective study conducted in the surgical wards of Adichunchanagiri Hospital and Research Centre (AH and RC). A total of 79 patients of acute pancreatitis, all from the rural areas surrounding the institute, admitted to AH and RC during the period from January 2014 to June 2016 were studied.

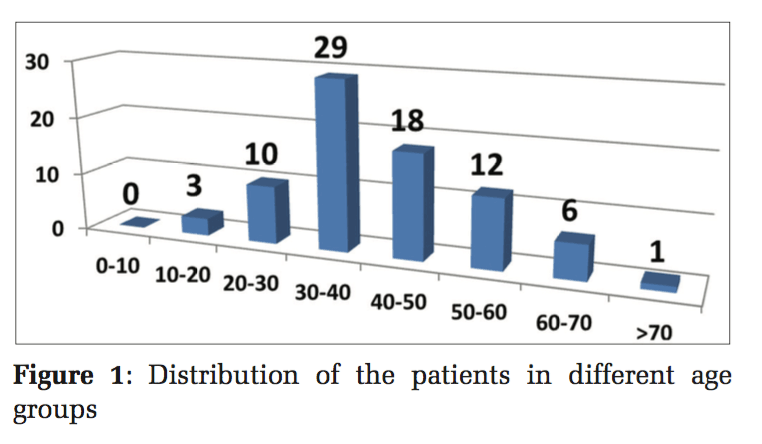

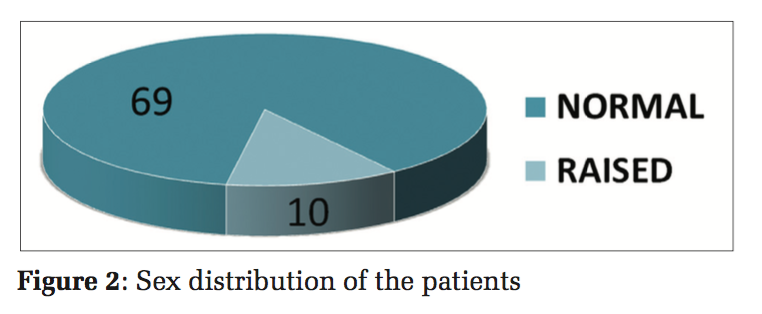

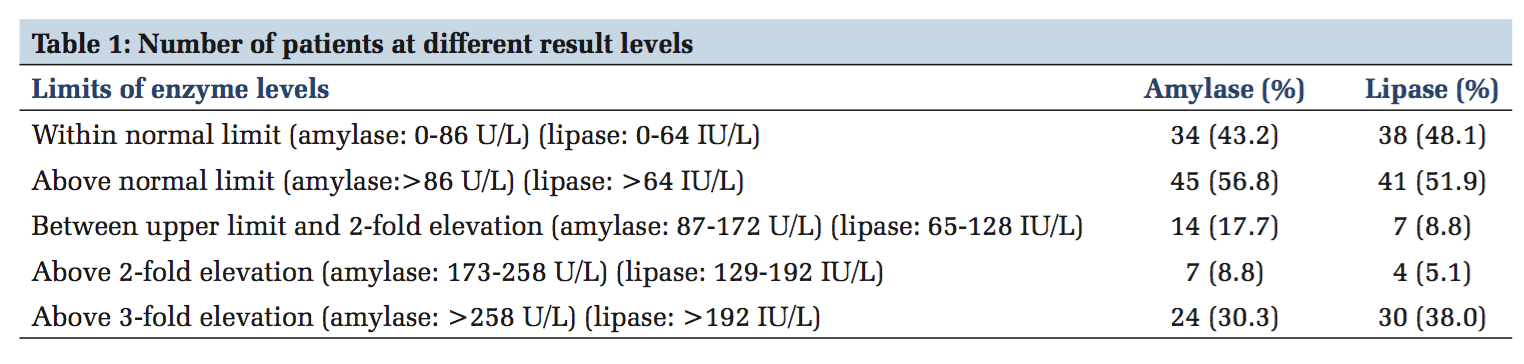

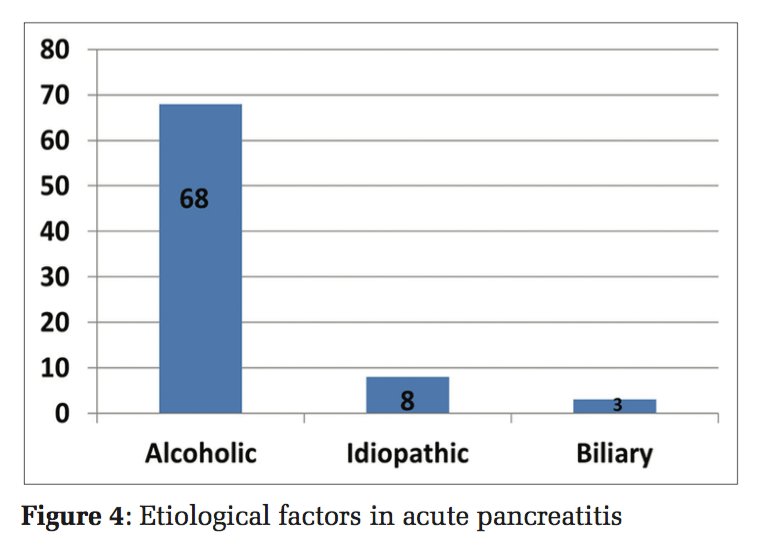

Results: The majority of patients fell in the age groups of 30-40 years (29 patients/36.7%) and 40-50 years (18 patients/22.8%). The sex distribution of patients in our study comprised 71 males and 8 females. The total number of patients with amylase level above normal value was 45 (56.8%) while that for the lipase was 41 (51.9%). The number of patients with above 3-fold elevation was 24 (30.3%) in the amylase group and 30 (38.0%) in the lipase group. Serum bilirubin was found to be within normal limits in 87.4% of cases (69 cases), whereas it was raised in 12.6% (10 cases). The etiological cause for acute pancreatitis was found to be alcohol induced in 68 patients. In 8 cases (all females), no specific cause was found and it was considered to be of idiopathic origin. Among 79 patients, 3 patients were found to have the cause of acute pancreatitis as biliary calculi. Complications: Pancreatic ascites was noted in 8 cases (10%). Pseudocyst was noted in 5 cases (6%). Mortality: 1 case diagnosed with acute severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Conclusion: The conclusion from this study was that in acute pancreatitis one should not only rely on enzyme level elevations for diagnosing acute pancreatitis. Patients with only a small increase in amylase and/or lipase levels or even with normal levels can also have or develop acute pancreatitis. Therefore, the clinician who makes the initial diagnosis of acute pancreatitis must evaluate the disease independently of the enzyme level elevations. High degree of suspicion is required; ultrasonography, computed tomography, and enzyme levels study are collectively complimentary to the clinical suspicion. Incidence of acute pancreatitis in rural population is increasing nowadays, probably due to alcohol abuse. Alcoholism ranks first as the etiological factor.

KEY WORDS:Pancreatitis, alcoholic, amylases, lipase, bilirubin

Acute pancreatitis is a common surgical emergency that we come across in the emergency wards. Alcohol abuse and biliary tract diseases are etiological in the majority of the cases.[1] The diagnosis is made by clinical examination which is supported by laboratory investigations and imaging studies.[2] There is as such no gold standard for diagnosing acute pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis should be suspected in a patient with history of biliary tract disease or alcohol abuser presenting with pain abdomen in the epigastria radiating to the back, vomiting, and distension of the abdomen. Serum amylase and lipase have been used as biochemical markers to diagnose acute pancreatitis for many decades.[3] The current UK guidelines[4] for the management of acute pancreatitis has emphasized the greater accuracy of serum lipase compared to amylase. Imaging studies such as ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) are confirmatory. Both may be normal in 15-20% of the cases. CT scan plays an important role in the prognostic information and identifying complications. The treatment of acute pancreatitis is mainly supportive with intravenous fluids (fluid resuscitation), analgesics, nasogastric aspiration, and H2-receptor blockers. Although the benefit of prophylactic antibiotics is doubtful, they are routinely added to the supportive treatment. Most of the acute pancreatitis are of mild to moderate severity and have good prognosis. The complications of acute pancreatitis are cardiopulmonary collapse, renal failure, or multi-organ failure, usually seen in acute hemorrhagic or severe necrotizing pancreatitis. The mortality in severe necrotizing pancreatitis or hemorrhagic pancreatitis is usually due to septic complications with mortality of 20-25%. In this set of patients, prophylactic antibiotics may be useful. Overall mortality is 5%.

The aim of our study is to evaluate the pattern of acute pancreatitis in the rural population and compare the role of serum amylase/lipase as diagnostic tool along with imaging studies and clinical examination.

This was a prospective study conducted in the surgical wards of the Adichunchanagiri Hospital and Research Centre (AH and RC) attached to the rural medical college Adichunchanagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, BG Nagar, Mandya district, Karnataka.

79 patients of acute pancreatitis, all from the rural areas surrounding the institute, admitted to AH and RC during the period from January 2014 to June 2016 were studied.

Data collection

The data were collected from the patients who presented to the Surgical Department of AH and RC with history suspicious of pancreatitis such as pain abdomen mainly in the epigastria and/ umbilical region radiating to the back and on evaluation were diagnosed with acute pancreatitis. The study period was from Jan 2014 to June 2016. The following data were collected: Name and address of the patient, hospital number, date of admission and discharge, age, sex, symptoms, signs, vitals, past history, laboratory data (hemoglobin, total count [TC], differential count, serum amylase/lipase, liver function test, and other investigations), ultrasonography findings, CT findings, treatment given, specific cause (alcoholic/biliary/others), any complications developed during treatment, and outcome of the disease.

Inclusion criteria

Patients diagnosed as acute pancreatitis based on the characteristic signs and symptoms as well as on the raised amylase and/or lipase in the serum and characteristic sonographic and/or CT findings were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with concomitant pathology causing the rise in amylase or lipase were excluded, for example, salivary gland disease, intracranial hemorrhage, and end-stage renal failure.

The distribution of the patients in different age groups was studied. The majority of patients fell in the age groups of 30-40 years (29 patients/36.7%) and 40-50 years (18 patients/22.8%) (Figure 1). The sex distribution of patients in our study comprised 71 males and 8 females (Figure 2). There is a male preponderance (71 out of 79 cases) in our study which coincides with most published series.

Variations in age and sex distribution among geographic regions likely arise from differences in etiology.[5] Alcohol-related pancreatitis is more common in men, though sex differences disappear with similar levels of alcohol consumption.[6] Although pancreatitis is uncommon among persons younger than 20 years old, it has been increasingly recognized in the pediatric population in recent studies.[7]

The number of patients with the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and normal enzyme levels was 34 (43.2%) in amylase group and 38 (48.1%) in lipase group. The total number of patients with amylase level above normal value was 45 (56.8%) while that for the lipase was 41 (51.9%). 14 (17.7%) patients had amylase level above normal but below 2-fold elevation while there were 7 (8.8%) such patients in the lipase group. 7 (8.8%) patients had amylase level above 2-fold but below 3-fold elevation while there were 4 (5.1%) such patients in the lipase group. The number of patients with above 3-fold elevation was 24 (30.3%) in the amylase group and 30 (38.0%) in the lipase group (Table 1).

Traditionally, serum enzyme levels 3 times above the normal are considered to be diagnostic of acute pancreatitis. Abruzzo et al. found hypoamylasemia in patients with acute pancreatitis and severe destruction of the pancreas.[8] Adams et al. found an inverse relation between amylase and severe morphological changes.[9] However, our study clearly demonstrates that patients with even normal enzyme levels and/or with only mild elevations can have acute pancreatitis.

Serum lipase is only secreted by the pancreas and thus better specificity and sensitivity. In acute pancreatitis, serum lipase level may be elevated more consistently and for a longer period than serum amylase.[10] The groups of Agarwal et al. and Thomson et al. reported a higher sensitivity and specificity in serum lipase levels for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis when compared to serum amylase levels.[11,12] Other authors have also observed similar results.[13,14]

Almost all the patients had presented with pain either in the epigastria or in the umbilical region radiating to the back. About 50% of the patients had associated nausea and vomiting. On examination, a significant tenderness was present in the epigastria and umbilical areas in all patients.

The TCs were significantly raised in the patients averaging about 14,000cells/cumm. Raised neutrophil counts were noted in 78% of the patients (62 cases).

Serum bilirubin was found to be within normal limits in 87.4% of cases (69 cases), whereas it was raised in 12.6% (10 cases) (Figure 3). Out of these 10 patients, 7 had acute pancreatitis due to alcoholism and 3 patients due to gallbladder calculi.

The etiological cause for acute pancreatitis was found to be alcohol induced in 68 patients out of the total 79. In 8 cases (all females), no specific cause was found and it was considered to be of idiopathic origin (Figure 4). Among 79patients, 3 patients were found to have the cause of acute pancreatitis as biliary calculi. 1 patient out of the 3 was diagnosed with acute severe necrotizing biliary pancreatitis. The patient had total bilirubin of 5.8 and had a higher elevation of enzyme levels: Amylase - 985 IU/L and lipase - 1200 IU/L. In the younger age group (10-30 years), with 13 patients, alcohol abuse was the significant etiological cause (10patients) with idiopathic origin in the rest (3 patients). A number of studies have reported that alcoholic acute pancreatitis was more prevalent in men and younger patients.[15,16] Our study also shows similar results. Some investigators have reported that patients with alcoholic acute pancreatitis have poorer prognosis compared to those with biliary etiology.[17-19] Other studies have reported that the clinical course, outcome, and mortality were not influenced by underlying etiology.[20,21]

The ultrasonography findings in patients who were diagnosed as acute pancreatitis on clinical examination were diffusely bulky and enlarged pancreas, with heterogeneous hypoechoic echotexture of the pancreas with or without dilatation of pancreatic ducts, with peripancreatic fluid collections. Similarly, the contrast-enhanced CT abdomen revealed more details with E/O calcifications, pseudocyst, walled off necrosis, parenchyma details, etc.

Ultrasonography (USG) is the cost-effective and reliable investigation for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis as well as its complications.[22-25] CT revealed all the features of acute pancreatitis and also complications such as necrotizing pancreatitis.[26-27] Its greatest advantage is its utility when retroperitoneum cannot be visualized on USG due to bowel gas.

Complications

Pancreatic ascites was noted in 8cases (10%). Pseudocyst was noted in 5cases (6%). The patients were treated conservatively in both the cases. 1 patient with pancreatic ascites underwent tapping. Additional test of enzyme levels (amylase and lipase) in the tapped ascitic fluid was done and it was found that the enzyme levels were elevated in comparison to the corresponding serum values. Mortality: 1 case diagnosed with acutesevere necrotizing pancreatitis succumbed to death following multiorgan failure.

Limitations of the study

The study was single-centered, prospective study and consists of only small group of patients. Further, larger studies are required. There was poor compliance with attendance at follow-up appointments by the patients. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) facility was not available at our setup and all such patients who needed ERCP, i.e., in cases of biliary calculi, were referred to higher center after improvement with initial conservative management.

Acute pancreatitis is an evolving, serious, and dynamic condition. The severity of acute pancreatitis is variable. The conclusion from this study was that in acute pancreatitis one should not only rely on enzyme level elevations for diagnosing acute pancreatitis. Patients with only a small increase in amylase and/or lipase levels or even with normal levels can also have or develop acute pancreatitis. Therefore, the clinician who makes the initial diagnosis of acute pancreatitis must evaluate the disease independently of the enzyme level elevations. High degree of suspicion is required; USG, CT, and enzyme levels study are collectively complimentary to the clinical suspicion. The incidence of acute pancreatitis in rural population is increasing nowadays probably due to alcohol abuse. Severity of pancreatitis can be determined early on in the disease process. The most cases of acute pancreatitis have a self-limiting course. Alcoholism ranks first as the etiological factor. Among the males, alcoholism is the most common etiological factor. The initial management for a case of acute pancreatitis is conservative with surgery reserved for those not responding to medical therapy and for those with complications.

We wish to thank all the patients who were part of the study, the Institution, the Department of General Surgery, the Department of Radiology and the Laboratory Unit of Adichunchanagiri Hospital and Research Centre, for their assistance, advice, help, and support.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.