Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2020.v06i03.004

Year: 2020, Volume: 6, Issue: 3, Pages: 19-26

Original Article

Zaid Ahmad Wani1, Shabir Ahmad Dar2, Maryam Hadiqa3, Deeba Nazir2, Shanoo Sheikh4

1Professor and Unit Head, Department of Psychiatry, Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir India,

2Senior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir India,

3MPhil Scholar, Department of Clinical Psychology, Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir India,

4Assistant Professor, Department of Clinical Psychology, College of Health and Rehabilitation, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Address for correspondence:

Shabir Ahmad Dar, Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Srinagar - 190 003, Jammu and Kashmir India. Phone: +91-7006296837. E-mail: [email protected]

Background: Fear experienced in health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) is crucial in guiding policies and interventions to maintain their psychological well-being. Our study was meant to assess fear and the use of faith as a coping mechanism used by the health care workers in the present pandemic.

Materials and Methods: This was a cross-sectional, online survey conducted among health care workers of COVID-19 and non-COVID hospitals. An online self-report questionnaire was developed to assess fear and faith and how health care workers cope/react to this infectious pandemic.

Results: The majority of respondents were male (65.6%), urban (69.3%), and postgraduates (87.3%) working in COVID- 19 hospitals (47%) and in the age group of 30–49 (67.5%) years. The majority (97%) of the participants reported the news about the illness as disturbing with (84.3%) even fearing govt. advisories. The fear for the lives of loved ones was found in almost all. Most of them (92.8%) had the belief that God/higher power will neutralize their threat which kept them going. However, a significant number of respondents reported depressed feelings (83.8%) and upsetting ruminations (94%). About 95.2% of surveyed reported faith had helped them to maintain a positive look and faith had helped to gain a sense of security and comfort in 92.2%.

Conclusions: Most of the participants feared for their own life and life of loved ones and also were having depressive symptoms and ruminations. Faith had helped them to maintain a positive look and to gain a sense of security and comfort.

KEY WORDS:Coronavirus disease-19, fear, god, punishment.

The outbreak of the novel coronavirus (2019-ncov, COVID) in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, has escalated into a serious health issue. It has rapidly spread globally and has been declared as a pandemic by the World Health Organization.[1] By April 26, more than 200 countries in the world had around 3 million people infected with around two hundred thousand dead. Its spread and lethality are proving to be higher than previous epidemics on account of international travel density and lack of immunity in the population.[2] This is threatening health care workers worldwide and subsequent draconian public health measures in many countries.[3] Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) is by far the largest outbreak of atypical pneumonia since the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003. Within weeks of the initial outbreak, the total number of cases and deaths exceeded those of SARS.[4] This has caused a situation that is unprecedented for everyone ranging from a common citizen to a policymaker. There has been also an effect on healthcare-related professionals and is being described as the worst public health crisis in a generation.[5,6]

During a pandemic, there is a feeling of fear as no one wants to get infected with a virus that has a relatively high risk of death.[7] The WHO report revealed that the mortality rate in COVID-19 is between 3% and 4%,[8] however, it seems that the morality statistics is underestimated.[9]

Fear and concern among the patients, general populace, and the health workers are understandable during an epidemic. However, this pandemic stands out in that the mortality and morbidity amongst health workers are considerable. As health workers are a closely watched group and serve as sources of inspiration and information for most of the sick and normal people, this pandemic has shaken a lot of people because of its secular effect. Our study is meant to assess fear and the coping mechanisms particularly faith used by the health care workers in dealing with this pandemic.

Study site

The study was conducted under the Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Kashmir, on medical workers working in hospitals.

Subjects

The subjects were the hospital staff including doctors, nurses, paramedics, and other supporting staff who worked in both COVID-19 only and non- COVID hospitals.

Survey procedure

Keeping in view the threat of COVID-19, its unprecedented nature and the subsequent lockdown, it was decided to have an online survey of the medical professionals. An online survey was preferable as it would also prevent the spread of COVID-19 due to paper questionnaires which could have acted as fomite and also it would have been easier despite the 2G speed of the internet. This was a cross-sectional, non-interventional study in which snowball sampling technique was used. This study made use of a survey link to direct participants to the survey in Google docs. This link was made available to participants through Facebook and sent individually to medical personnel and their groups through WhatsApp. Many participants complained of slow internet speed and difficulty in the loading of the survey pages. Despite very slow internet speed due to the political situation in this part of the world, a total of 175 responses were received. Out of these 9 were incomplete and were not included in the final results. The first page of the survey consisted of the information page regarding the purposes of the study, how the data would be used, anonymity, and confidentiality. Participants were then asked to provide consent and confirm. The last page included a feedback column along with a helpline to seek any professional help if needed.

Study tool

The study tool was an online self-report questionnaire related to COVID-19. It consisted of 4 sections with a total of 35 questions. The questionnaire was validated in the Kashmiri population and the Cronbach’s α was found to be 0.77, meaning an acceptable consistency.

Questionnaire sections

Section first or the demographics section included 10 questions related to age, gender, marital status, residence, religion, specialty, place of posting in a COVID-19, or a non-COVID hospital.

Section two or the fear section included questions related to fear of infection for oneself and family, fear due to media advisory of government and social media, and fear of lives of yourself and family, view that COVID-19 pandemic is a punishment/justice from God, involved with religious activities more than usual, protection by engaging in acts of “good deeds.” Belief in God helping in neutralizing fears?

Section three or the current emotional concerns section used five questions related to feelings of being depressed, irritability, feeling panicky, or having upsetting thoughts and feeling of surroundings as unreal.

Section four or the religious and faith section included questions such as the persons view about God, view about rituals, and practices in religion. Faith enabling to maintain a positive outlook? Being angry at God and felt grateful for anything in life? The other questions were related to the frequency of praying, reading of religious scriptures, and feeling about the closure of religious places, and if the current events shook the faith in God.

All the questions in section two to four were marked as lowest as not at all, slightly, definitely, markedly, and very severely as the highest with exception of questions related to the frequency of praying, reading of religious scriptures, and view of God.

This study was approved by the IEC.

Descriptive statistics using frequency and percentages were used to describe the sample characteristics and scores on different scales.

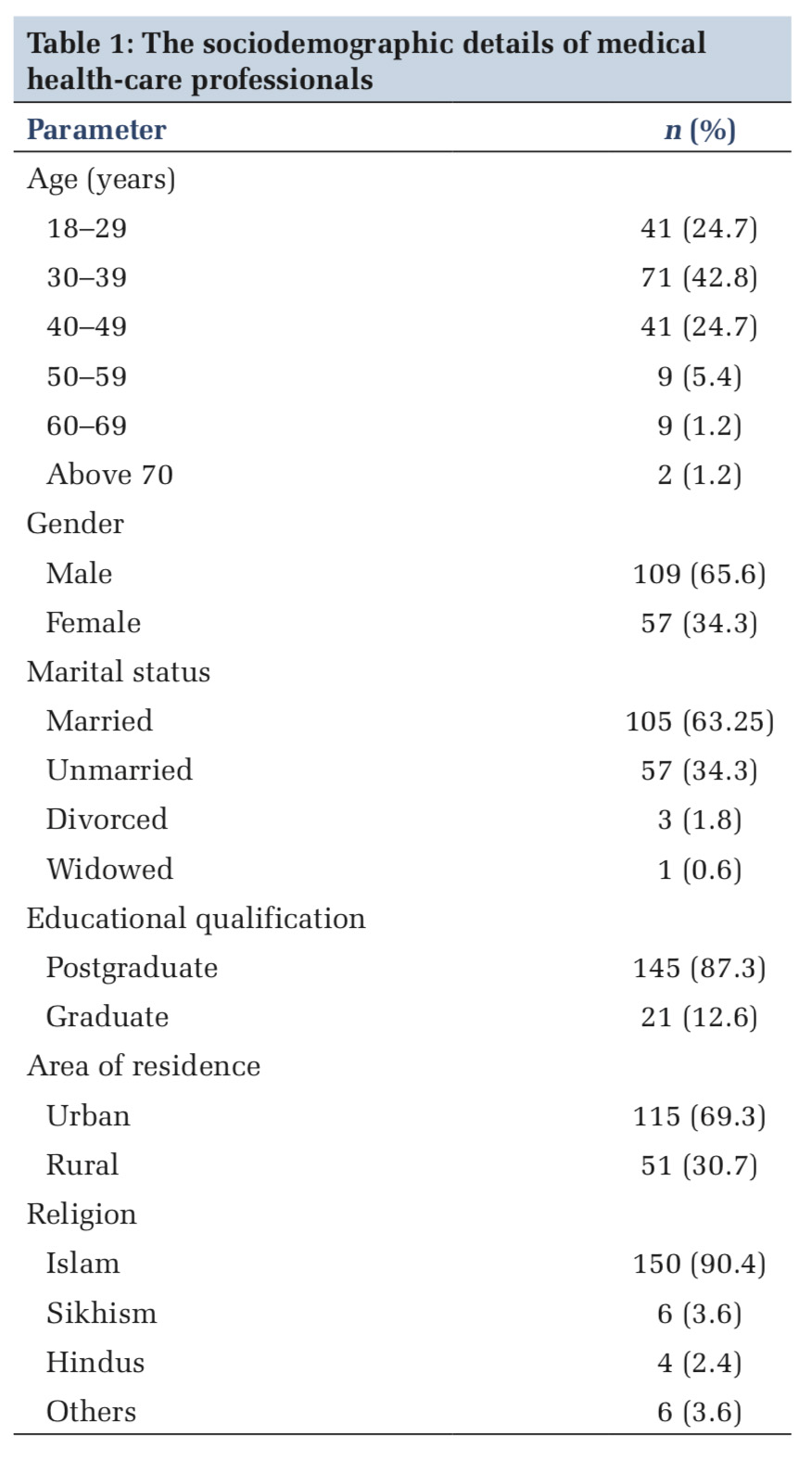

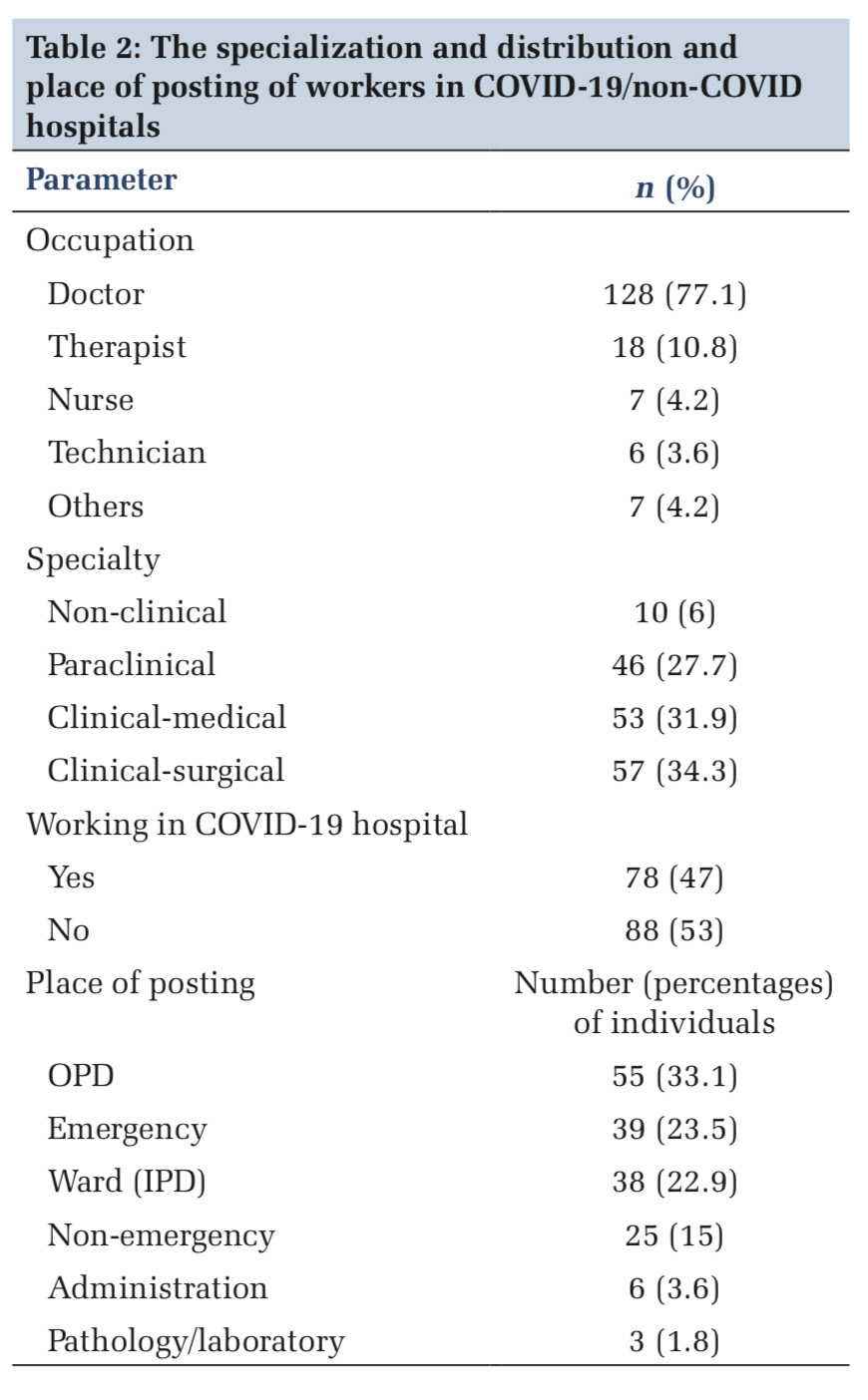

Most of the medical health-care professionals were in the age group of 30–39 years (42.8%), approximately two-third of them males (65.6%), majority of them married postgraduates. The maximum number of them were residents of urban areas and Muslims, as shown in Table 1. The majority of participants were doctors either from the medical or surgical side with an almost approximate number of them working in COVID-19/non-COVID hospitals as shown in Table 2. The majority of our study participants were either posted in an outdoor patient department or emergencies, as shown in Table 2.

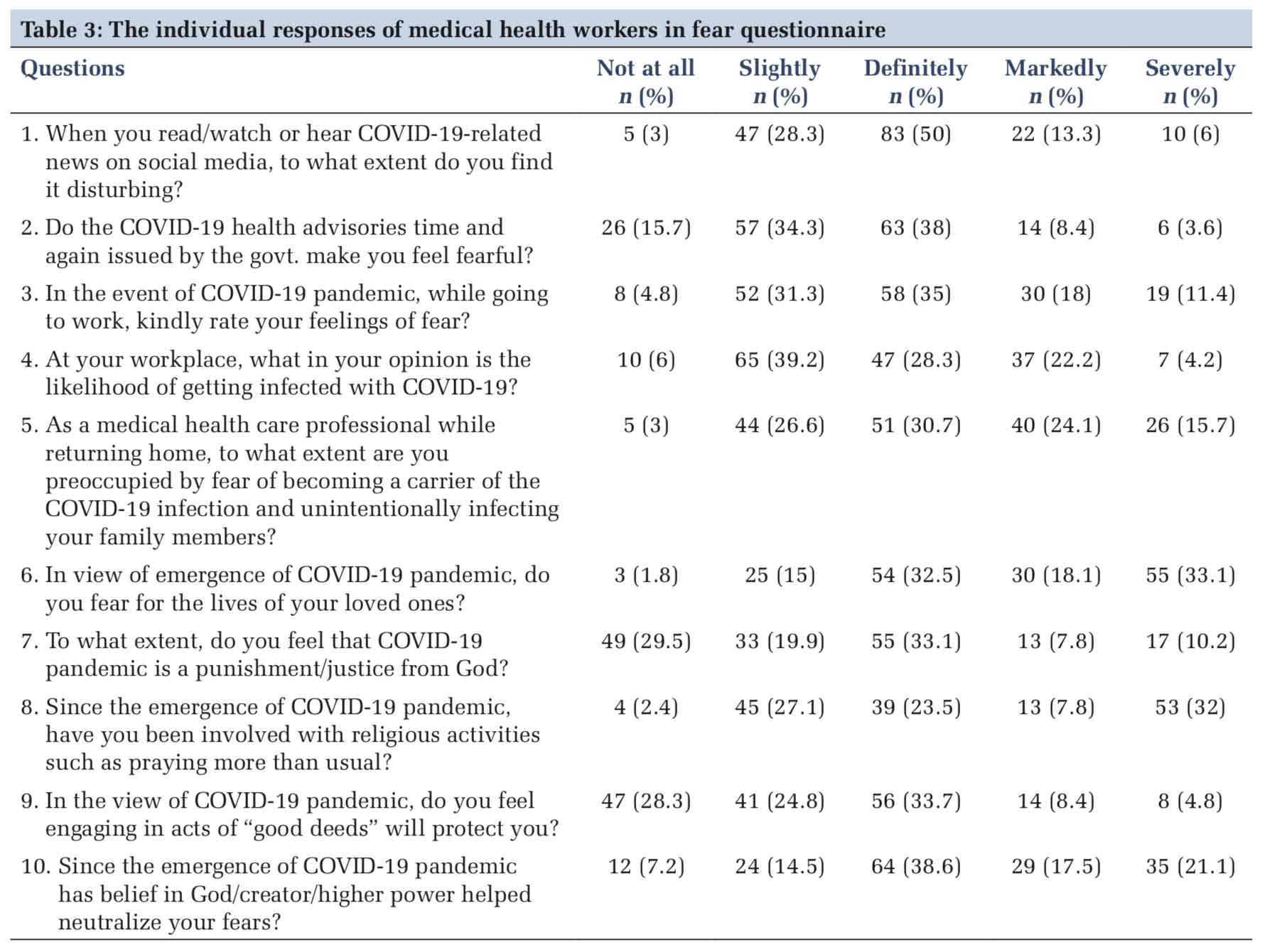

Most of the participants reported hearing or watching of news either definitely or markedly disturbing (97%). Most of them feared the govt. advisories (84.3%). Almost half of them feared the life of their loved ones (98.2%).

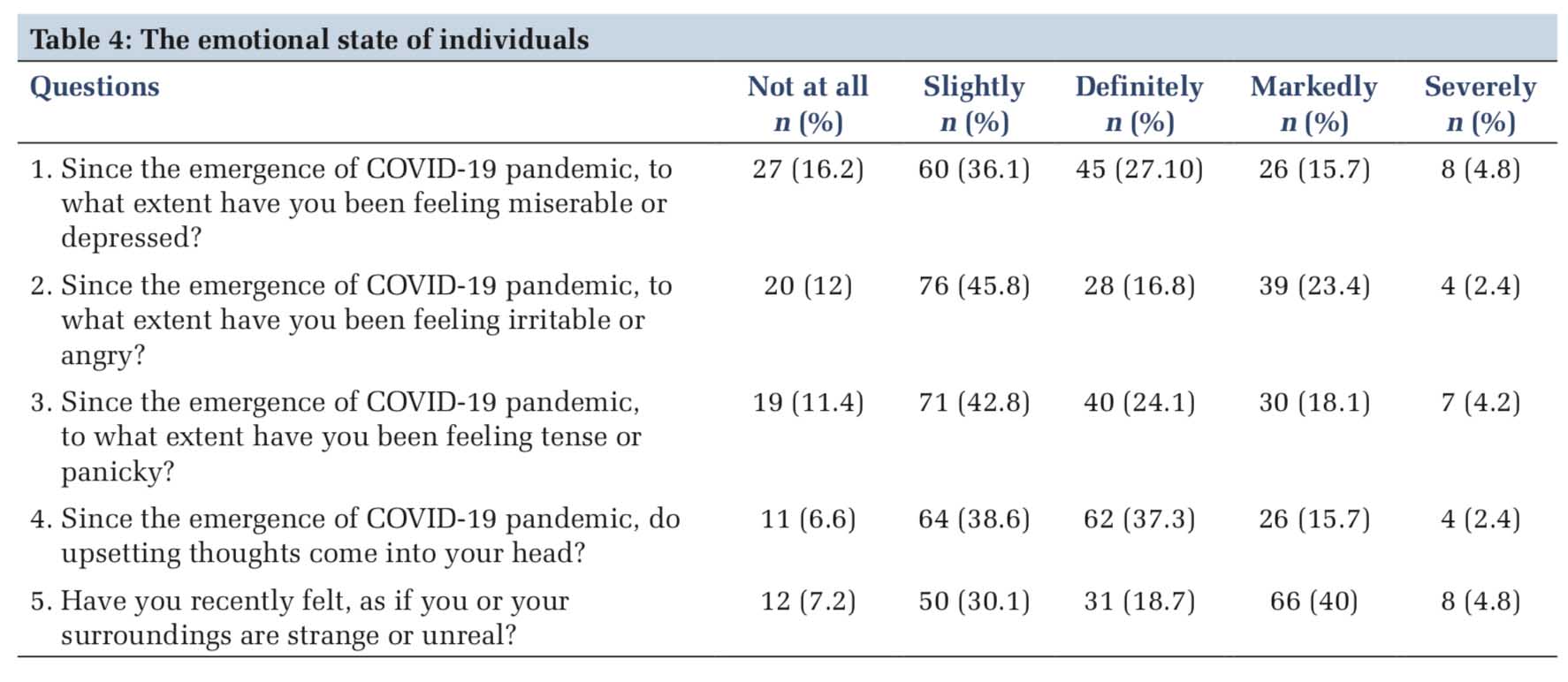

Most of them (92.8%) had a belief that God/ higher power will neutralize their threat, as shown in the Table 3. Most of the respondents had an impact of depressed feelings, upsetting ruminations (83.8%). More than half (92.8%) felt their surroundings either strange or changed, as shown in Table 4. Around 50% of cases reported that they had faith to maintain a positive look, as depicted in Table 5.

Tables 6-9 show common views about God, rituals/ practices prescribed during a pandemic, reading religious scriptures, and frequency of praying to overcome the fear of the current pandemic.

This disease (COVID-19) is being seen as an enemy, which brought death and destruction by invading the global psyche with fear and the bodies of most vulnerable citizens with a lethal illness. For most people, almost every aspect of daily life has changed such as social interaction, professional involvement, and finances. COVID-19 strikes indiscriminately, with no preference for borders, gender, race, ethnicity, or social class, and poses challenges never seen before.[10]

Around 70% of respondents felt that hearing/ watching the news on social media is disturbing. Due to global and instantaneous outreach of social media, fear of contagion spreads faster than the dangerous yet invisible virus. Announcements of mass cancellations of gatherings, lockdowns, TV stations showing panic buying, and discussions on social media regarding various aspects of the pandemic exacerbated chaos and uncertainty. Along with the general population, this distress was also found in our staff which caused distress in them. Experience from SARS and H1N1 epidemics underlines that the psychological strain on health-care professionals, who find themselves at the frontline of attempts to quell the outbreak, is significant.[5]

Approximately 70% of health care workers were anxious about contracting the disease, more than two-third felt worried of getting infected or becoming a carrier and infecting family. Around 66% of the staff did feel fearful during the outbreak and just performed their duties for ethical obligations. Due to the increased risk of exposure to the virus, the fear of contracting the virus was found in frontline doctors, nurses, and health care workers. Furthermore, there is worry about bringing the virus home and passing it on to loved ones and family members. Health-care staff also reported increased stress levels when dealing with patients unwilling to cooperate or not adhering to safety instructions and feelings of helplessness when dealing with critically ill patients, in the context of limited intensive care beds and resources. The use of protective equipment for long periods causes difficulties in breathing and limited access to toilet and water, resulting in subsequent physical and mental fatigue. Very similar experiences of health-care personnel have been recorded in the emerging scientific literature.[5]

The first case of SARS-COV-2 in Kashmir came to the limelight when a female with a history of foreign travel tested positive for the infection.[11] As soon as the first case of virus came into the limelight in Kashmir, the government responded by the closing of schools, imposition of travel restrictions on public transport, suspension of the commercial fights, and closing of land borders this lead to fear and uncertainty in people including the medical frontline workers. The J&K government has implemented strict self-quarantine and forced quarantine measures across the UT. The mass restrictions were placed 1 week before the rest of the country and this mass quarantine added fuel to the fire.

Mass quarantine has in many ways acted as a double-edged sword. First, the measure shows that authorities believe the situation is going to be severe and liable to worsen day by day. Second, quarantine meant a loss of control and a sense of being trapped.

The rumor mills are working overtime, thereby creating chaos and panic among the common people. The impact of the rumor mill must not be underestimated. The desire for facts will escalate and an absence of clear messages will increase fear and push people to seek information from less reliable sources.[12]

In our case, the rumor was perpetrated by very slow internet speed which meant that people were relying more on word of mouth and WhatsApp. The most devastating experience for family members of those who had died from the infection was that they could not claim the body of their loved one to perform their last rights.

At the core of all these conditions lies elements of one of the most basic and primal human emotions – fear. Fear is an emotional response induced by threats that are perceived to be unavoidable or uncontrollable.[13]

The fear in the medical community was no different. The fear took many forms in them prominent among them was the fear that they will contract the virus (54%) and that their near ones will get the virus because of them. This increased due to scarcity of protective equipment at least initially and especially when people saw healthy colleagues around the world as young as they end up on ventilators and many of them dying subsequently.

The other from how the fear manifested was that more than half of the participants reported that it’s a punishment from God and got involved in religious activities like praying more than usual. They got engaged in acts of good deeds to neutralize fears.

Faith in a religious context is defined as belief and trust in God or religious teachings.[14] Faith was the silver lining in most of the participants although COVID-19 seems to be testing the faith of the faithful. In modern history, it’s the first time that worshipers to God were not allowed where into places of worship. Some of them believe that the virus was sent by God to punish humanity for losing its way while others attributed this to atrocities against mankind by rulers usurp their powers and suppressing their subjects.[15]

However, most of the medical workers did not believe it as a punishment, nevertheless, they have increased the praying as well as good deeds. This shows that faith has been an important protective coping mechanism to ward off the anxiety and fear caused by the pandemic.

Faith is a durable and necessary solace for the lonely health worker. A lot of respondents in our study mentioned that faith enabled them to a positive outlook. The majority of them did not feel angry with God. Religion and spirituality have many components that are of potential relevance to mental health, including religious attendance, private religious activities (e.g., prayer and reading of Holy Scriptures), a feeling of connection or relationship with God or a higher power, religious beliefs, and religious coping. Besides, religion and spirituality may be good for mental health through healthy lifestyles and behaviors and the promotion of social support. Religious practices may facilitate the adoption of healthier lifestyle behaviors and are important in shaping how people perceive their health and engage in self-care.[16,17]

This will help also people to be more resilient and not succumb to mental illness. However, certain religious beliefs may, conflict with recommendations by medical professionals, inhibit healthcare utilization and may lead to poor treatment adherence.[18] This may include the belief that we are immune from the illness, thereby involving in risky behavior of organizing religious gatherings and defeating the purpose of social or physical distancing as recommended by the WHO. As was been seen previously study and in unison with our study, people often convert to religion in times of distress in a difficult life situation.[19]

Most of the health care workers had felt miserably depressed, panicky, and irritable. It is a known fact that those who are on the frontlines in treating the sick can experience psychological effects. The disruption of routine clinical practice, the sense of loss of control, and the subsequent fear of potential destabilization of the health services have provoked “overflowing” anxiety and depression among health-care professionals, a feature that is not uncommon in epidemics.[20,21]

As medical workers and the common people have never faced a situation like this in their lifetimes and death was a reality, these reactions were expected. This has been widely reported in the previous literature also. In the early rapid expansion phase of the SARS outbreak, similar to the current course of COVID-19 pandemic, health-care professionals reported feelings of extreme vulnerability, uncertainty, and a threat to life, alongside somatic and cognitive symptoms of anxiety, while during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, more than half of the health care workers in a Greek tertiary hospital reported moderately high anxiety and subsequent psychological distress.[5,6]

Limitation of the study

The major limitation of the study was that it was a cross-sectional study so what happens to fear overtime could not be elicited. Second, small sample size and single-center study done in particular geographical area may limit the generalizability of the study. Third, since it was an online survey, lack of knowledge about non-responders and use of self- rated questionnaire might have biased the results.

Most of the participants feared for their own life and life of loved ones and also were having depressive symptoms and ruminations. Faith had helped them to maintain a positive look and to gain a sense of security and comfort. Religious activities and spirituality seem to alleviate that fear. Coping with stress in a healthy way will make you, the people you care about, and your community stronger.

Authors would like to thank Dr. Shabir Ahmad Dhar, associate professor, Department of Orthopedics, SKIMS Medical College, Srinagar, for his innovative ideas about COVD-19 crisis and invaluable help. Authors would also like to thank all front-line health-care heroes who despite very hectic schedule made this manuscript a reality.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.