Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2021.v07i01.005

Year: 2021, Volume: 7, Issue: 1, Pages: 25-31

Original Article

Avita Rose Johnson1, Shweta Ajay2, H. N. Swathi3

1Assistant Professor, Department of Community Health, St. John’s Medical College, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India,

2Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, The Oxford Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India,

3Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Shimoga Institute of Medical Sciences, Shivamogga, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Avita Rose Johnson, Assistant Professor, Department of Community Health, St. John’s Medical College, Sarjapur Road, John Nagar, Bengaluru - 560 034, India. Phone: 080-49466133. E-mail: [email protected]

Background: Birth-preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) is an evidence based strategy to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality. This study aims to assess awareness of BPCR and its determinants among pregnant women in a rural area of Ramanagara district, Karnataka, South India.

Materials and Methods : A cross-sectional hospital-based study among pregnant women availing antenatal care, using the interview schedule from Johns Hopkins Program for International Education in Gynaecology and Obstetrics BPCR Tools and Indicators for Maternal and Newborn Health, with 41 items of BPCR awareness scored one for each correct response. Statistical analysis was performed using independent t-test, One-way ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation, and multi-logistic regression.

Results The 331 pregnant women had low mean BPCR awareness score of 9.46 ± 3.61. Commonly mentioned obstetric danger signs were vaginal bleeding, severe weakness, and headache. BPCR awareness was significantly higher among multi-gravidae (P < 0.001), those with previous bad obstetric history (P = 0.002) or complications in the previous pregnancy (P = 0.031), those who registered their pregnancy early (P = 0.018) and those with four or more antenatal check-ups (P = 0.006). Multi-gravid mothers were twice more likely to have higher BPCR awareness than primigravidae. (Odds ratio = 2.41 [1.49–3.34], P < 0.001).

Conclusions: Awareness of birth preparedness and obstetric danger signs among women in our study was found to be low. None of the women were aware regarding identifying a blood donor in advance in spite of vaginal bleeding being the most commonly cited danger sign. This study reveals an urgent need to address the lack of awareness of BPCR among rural women during routine antenatal visits or by community-level workers during home visits.

KEY WORDS: Birth preparedness, complication readiness, danger signs, rural women, awareness.

KEY MESSAGES: This study highlights the poor awareness of birth preparedness among pregnant women in rural south Karnataka. There is a need to educate mothers-to be regarding obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness to prevent delay in seeking care or reaching care in time.

Maternal and child survival continue to be a challenge in developing countries. With the current Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in India at 122/100,000 live births[1] and perinatal mortality at 26/1000 live births,[2] India still has a long way to reach the maternal and child health targets under the Sustainable Developmental Goals, 2030 of reducing MMR to 70/100,000 live births and ending preventable causes of neonatal mortality. [3]

The common causes of maternal and perinatal deaths are hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, obstructed labor, and infections and often occur because of the three delays propounded by Thaddeus and Maine[4] (i) delay in deciding to seek care; (ii) delay in reaching care; and (iii) delay in receiving care.

The Maternal and Neonatal Health Program of Johns Hopkins Program for International Education in Gynaecology and Obstetrics (JHPIEGO) developed the birth-preparedness and complication readiness (BPCR) strategy to address these three delays at various levels: Individual, family, community, health-care facilities, and policy-makers. BPCR is one of the evidence-based strategies to reduce the burden of maternal and perinatal deaths.[5] BPCR means identifying a trained birth attendant for delivery, identifying a health facility for emergency, arranging for emergency transport, saving money for delivery, and identification of compatible blood donors. Complication readiness indicates awareness, of danger signs during pregnancy, delivery, postpartum and newborn period, thereby leading to problem recognition and reducing the delay in deciding to seek care or reaching medical facilities.[5]

Awareness of health services tends to be poor in rural areas due to lack of education and lack of access to information.[6] For any public health strategy to be successful, awareness or information literacy among beneficiaries is vital to ensure practice or utilization. Despite the fact that BPCR is essential for improvement of maternal and child health indicators, little is known about the awareness BPCR among rural women in India. This study, therefore, seeks to assess the awareness of BPCR and its determinants among rural mothers, with the intention of providing vital evidence for designing community-based targeted interventions to ensure BPCR among rural women.

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in a rural maternity hospital in a village around 70 km from Bengaluru city, in Ramanagara district, Karnataka state, in South India. This hospital is a 50-bedded missionary-run private hospital, with 180–200 outpatients/day and 120–150 deliveries in a month, also provides emergency obstetric care including caesarean sections. Normal deliveries are conducted by qualified trained staff-nurses and medical interns, while cesarean sections are conducted by a resident obstetrician along with anesthetist. After receiving Institutional Ethics Committee approval, the data collection was done over a period of 2 months by medical interns who were trained in obtaining consent and administering the study tool, and the data analysis and manuscript writing were done over a 3 months period, in 2019. The study population included all pregnant women availing outpatient department antenatal care services at the hospital. Based on the results of a previous study,[7] where 74.7% of the mothers were found have adequate knowledge of birth preparedness; with 5% absolute precision, 95% confidence limits, and 10% non-response rate, the sample size was calculated to be 319. Consecutive sampling technique was employed; however, as data collection was done simultaneously by medical interns, the final sample size slightly exceeded the estimated sample size.

Inclusion criteria

All pregnant women attending the outpatient antenatal clinic at the rural hospital who consented to participate in the study, irrespective of gestational age were in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant women in labor, who were seriously ill or not able to comprehend the questions due to any mental health disorders were excluded from the study.

After obtaining written informed consent, a pre- tested structured interview schedule from JHPIEGO’s BPCR Tools and Indicators for Maternal and Newborn Health[5] was administered after translation into the local language Kannada. It had two parts: (i) Socio- demographic and obstetric details of the respondent and (ii) 41-item BPCR awareness (including obstetric danger signs). Each correct response was given a score of one. A maximum BPCR awareness score of 41 was possible. Socio-economic class was determined using the Modified BG Prasad Socio- economic Classification, based on monthly per capita income.[8]

The data were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed using STATA version 12 data management software (StataCorp, Texas, USA). The socio- demographic variables were described using proportions, mean and standard deviation. The outcome variable in the study was BPCR awareness score. Normal probability plot was used to assess normal distribution of data. Pearson’s correlation co-efficient test was used to correlate BPCR awareness score with continuous exposure variables such as age, years of formal education, and gestational age. Independent t-test and One-way ANOVA test were used to test the difference between the mean BPCR awareness score among the various socio- demographic and obstetric variables. Factors found to be significantly associated with awareness of BPCR were entered into a multiple regression model. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

A total of 331 pregnant women participated in our study with a mean age of 22.9 ± 0.16 years. All the subjects were married and the mean age at marriage of 20.3 ± 0.13 years. The mean number of years of formal education was 10.3 ± 0.13 years for the subject and 10.2±0.15 for the spouse. Majority of the subjects were Hindu by religion (93%).

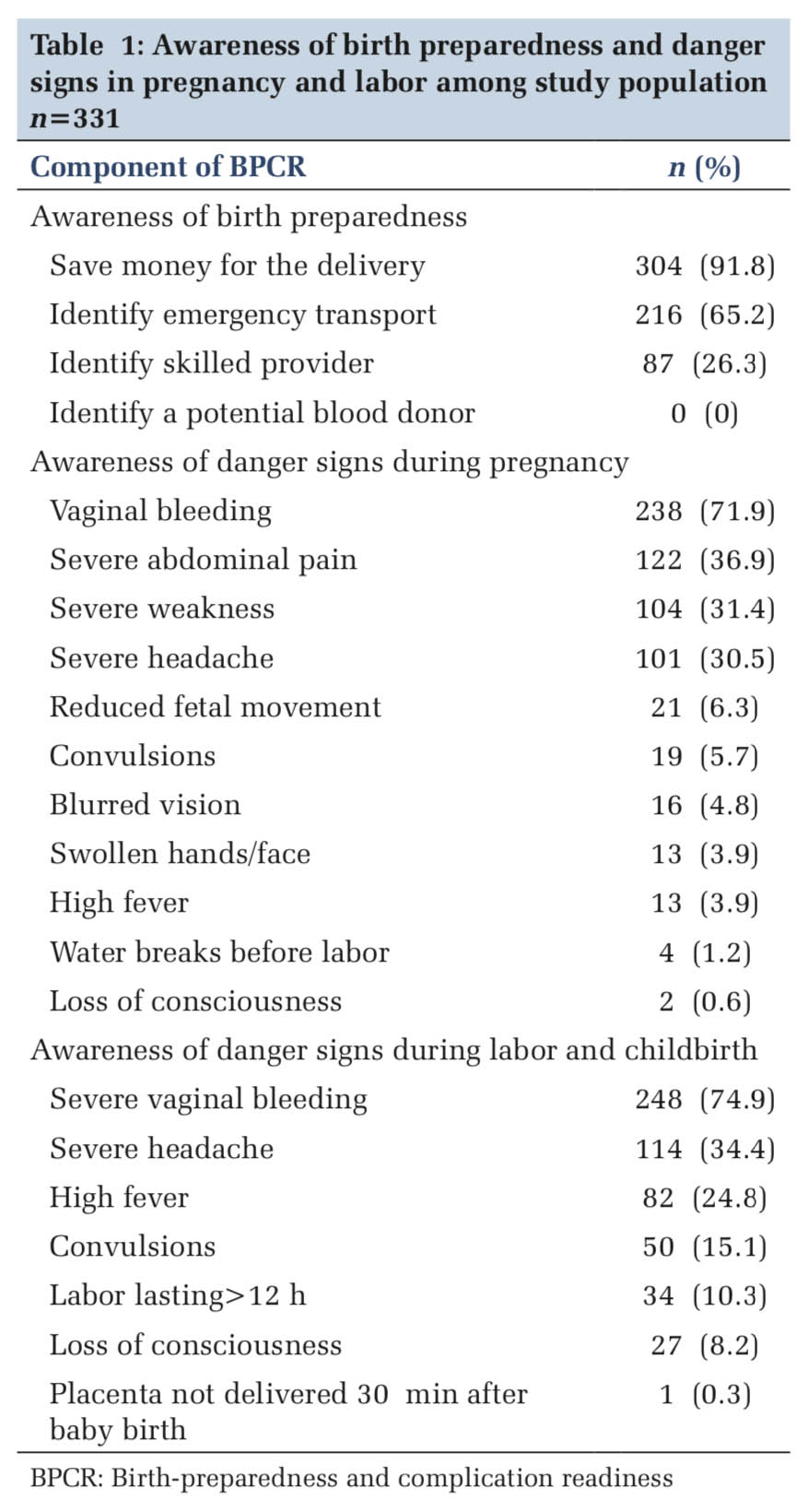

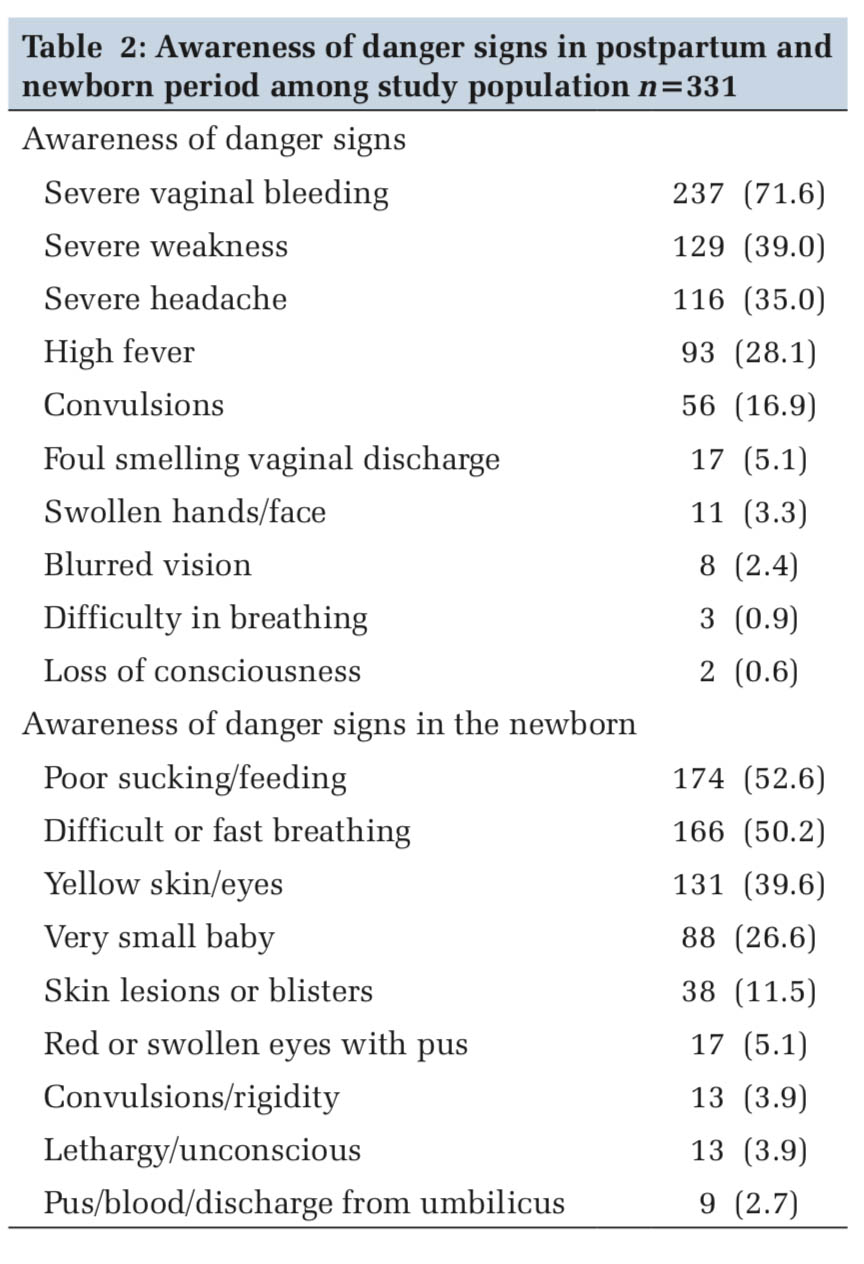

Regarding awareness of danger signs, the most commonly mentioned ones during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum period were vaginal bleeding, severe weakness and headache (Tables1 and 2). Awareness regarding loss of consciousness, blurring of vision, and swollen hands/face was very low. Women were more aware of poor sucking/feeding and difficult/fast breathing in the newborn, but not about purulent discharge from umbilicus or convulsions/rigidity. While most mothers were aware of saving money for the delivery (91.8%) and identifying emergency transport (65.2%). Only 26.3% knew about identifying a skilled provider and none were aware regarding identifying a potential blood donor.

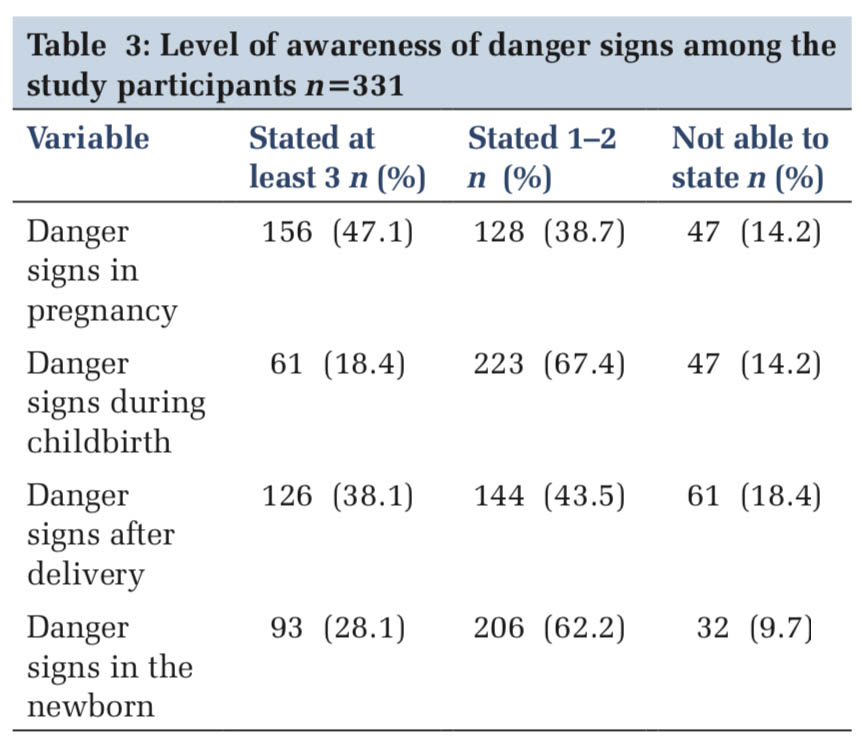

Only 15 (4.53%) women were able to state at least three obstetric danger signs in each of the four situations; pregnancy, childbirth, delivery, and newborn (Table3). There were mothers (9–15%) who were not able to state even a single obstetric danger sign.

While the total BPCR awareness score ranged from 1 to 19, out of a maximum possible score of 41, mean BPCR awareness score was found to be 9.46 (SD ± 3.61), and median BPCR awareness score was 10 (IQR = 8.12); all values indicating poor level of awareness regarding BPCR.

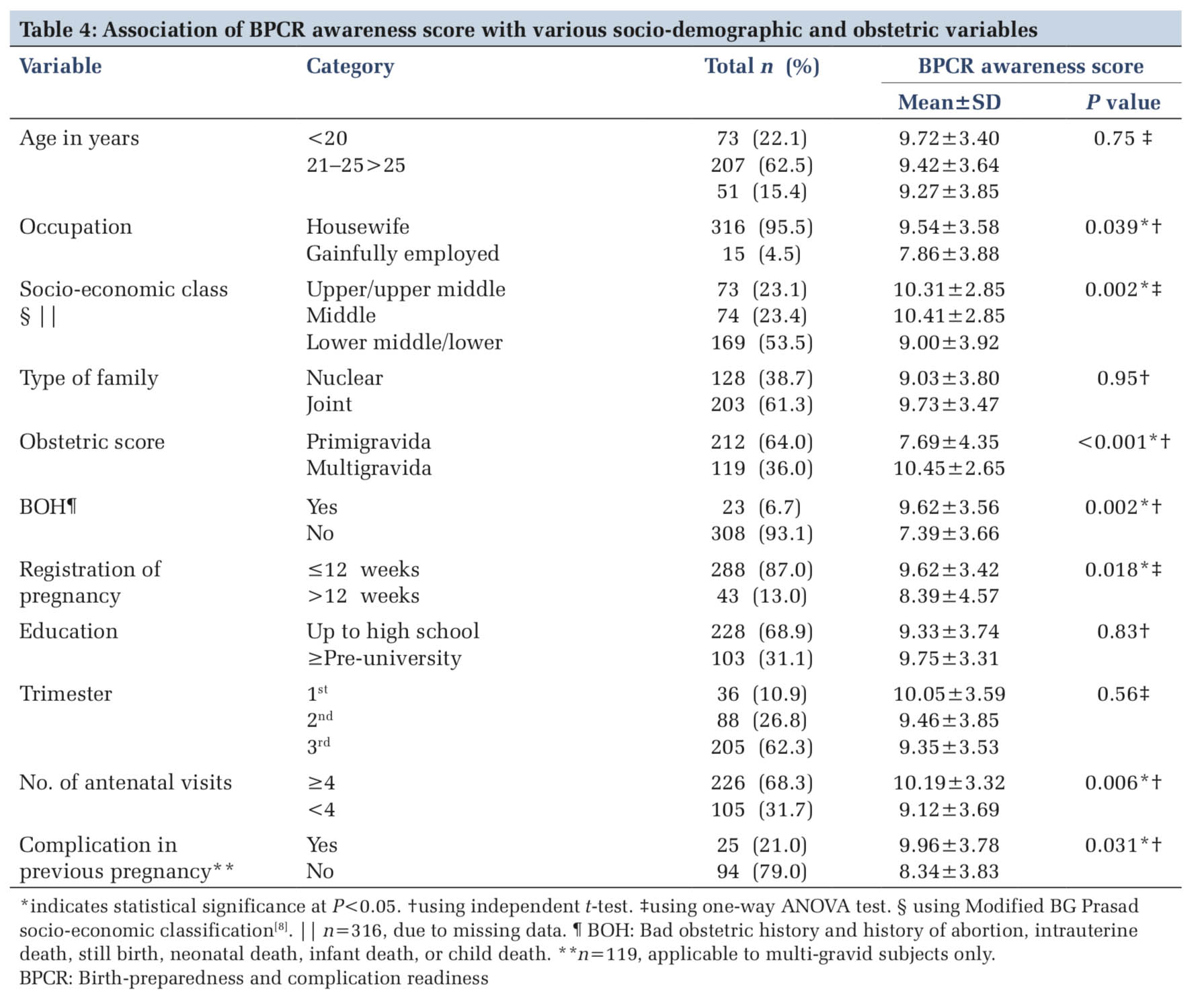

The mean BPCR knowledge score was found to be significantly lower among low socio-economic class (P = 0.002) and among those who were gainfully employed (P = 0.039) (Table 4). The scores were significantly higher among multi- gravidae (P < 0.001), those with bad obstetric history, that is, any history of abortion, intrauterine death, still birth, neonatal death, infant death or child death (P = 0.002), complication in previous pregnancy (P = 0.031), those who registered their pregnancy before 12 weeks of gestation (P = 0.018) and those who had four or more antenatal check- ups (P = 0.006). Pearson’s correlation test revealed no significant correlation between BPCR awareness scores and age, education or gestational age. On regression analysis, obstetric score retained significance, with multigravida mothers being more than twice likely to have higher BPCR awareness score than primigravidae (Odds ratio =2.41 [1.49–3.34], P < 0.001).

The findings of our study have shown that pregnant women in a rural area of South Karnataka, lack awareness of BPCR. We assessed “awareness” rather than “knowledge” as in the knowledge domain, general awareness sits at the lower end of the continuum, and knowledge which is considered detailed and specific sits at the higher end.[9] Less than one in 20 women in the present study were able to state at least three obstetric danger signs and more than 1 in ten mothers were not able to state even a single obstetric danger sign. Poor awareness of obstetric danger signs has also been found in an urban hospital in Mangalore, coastal Karnataka.[10]

There is enough evidence to show that being well prepared for birth is significantly associated with awareness of obstetric danger signs.[11-13] Therefore, it may be surmised that this large gap in awareness of BPCR could lead to poor preparedness for birth. The WHO has recommended that all pregnant women should have a birth plan.[14] However, when women are not adequately aware of danger signs and how to prepare for birth, having a birth plan becomes impossible.

While vaginal bleeding was the most frequently mentioned danger sign, none of the mothers were even aware that it is important to identify a potential blood donor for emergencies. This finding indicates that women need to understand the connection between the danger of vaginal bleeding and planning for such an eventuality by arranging a blood donor in advance. These results resonate with those in a study in rural West Bengal, where women made savings toward delivery more than making arrangement for a blood donor.[15] Similar findings have been also been demonstrated in an urban setting in Hyderabad, where 89% of pregnant women did not identify a blood donor in spite of citing vaginal bleeding as a danger sign.[16] This finding seems to echo across other lower- and middle-income countries such as Cameroon in Central Africa[17] and Jordan in the Middle -east.[18]

Awareness regarding blurring of vision, swollen hands/face and loss of consciousness was very poor. With 14% of global maternal deaths attributed to hypertension,[19] pregnant women need to be made aware of these particular danger signs which are signs and symptoms of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. We found that visually-obvious signs in the newborn such as skin lesions/blisters, red/swollen eyes with pus, blood/pus from umbilicus, or convulsions/rigidity were not mentioned as danger signs. The public health implication of this finding is that the lack of awareness of these signs could lead to delay in deciding to seek care for the newborn with fatal consequences. Similar findings were demonstrated in a facility-based study in Central Africa.[17] These finding of ours was in contrast to a study in Thailand[7] where three-fourths of the mothers cited swollen hands/feet and blurred vision as danger signs in pregnancy and 80% cited convulsions and unconscious/lethargy as danger signs in newborn. This may be due to the difference in the socio-demographic composition of their study subjects, who were from urban and higher economic background.

We found that experiential learning plays a role in awareness of BPCR, as multi-gravidae and women with bad obstetric history or complication in the previous pregnancy had significantly higher awareness of BPCR, drawing from their past experience with pregnancy, delivery, and newborn care. This is substantiated by the finding from our regression analysis that multigravida mothers were more than twice more likely to have higher BPCR awareness than primigravidae. BPCR awareness was also higher among those who had early registration of pregnancy and those who had four or more antenatal check-ups, irrespective of their gestational age. This shows that increased and early contact with the health system provides an opportunity for increased interaction with health-care providers and dissemination of information pertaining to BPCR. A study on BPCR in an urban tertiary care hospital in Hyderabad[16] demonstrated that multiparity and early registration of pregnancy were significantly associated with adequate practice of BPCR. These findings are also in consonance with those in a community-based study in Southern Ethiopia which found that women with four or more antenatal visits were nearly 5 times better prepared for birth.[13]

In our study, BPCR awareness was lower among those who were of low socio-economic status, a finding matched by a study in Ethiopia which also found that low incomes were linked to low awareness.[12] We also found that those who were gainfully employed had poorer awareness of BPCR. This was in contrast to a study in Malaysia,[20] which found that working women had higher level of knowledge of danger signs. This is due to the fact that working women in Malaysia tend to be of higher socio-economic status and higher education, whereas in the socio-cultural context of our study area, women from poorer families often seek employment outside the home to supplement family income, while those of higher economic status are home-makers.

The Mother and Child Protection (MCP) Card provided by the government health system to all pregnant women on registration of their pregnancy has detailed pictorial depiction of obstetric danger signs and birth preparedness.[21] A study in rural Karnataka found that husbands of pregnant women had higher awareness and participation in BPCR when they accessed mobile phones for BPCR-related information.[22] It is recommended that to improve awareness of BPCR, community-level healthcare workers may utilize antenatal visits and home visits as an opportunity to counsel women and their families, using MCP card as a tool for health education about BPCR, while policy makers may additionally explore the option of harnessing mobile phone technology to educate and prepare women for birth.

Limitations

Our study was not without limitations. Being a hospital-based study in a rural area, the results may not be generalized to all rural women in the community.

Overall awareness of birth preparedness among pregnant women in the rural area of our study was found to be poor. None of the women were aware regarding identifying a blood donor in advance in spite of vaginal bleeding being the most commonly cited danger sign. The mean BPCR knowledge score was found to be significantly lower among low socio-economic class, and gainfully employed women, and significantly higher among multi- gravidae, those with bad obstetric history, complication in previous pregnancy, those who registered pregnancy early, and those with four or more antenatal check-ups. On regression analysis, obstetric score retained significance, with multigravida mothers being more than twice likely to have higher BPCR awareness score than primigravidae. This study has revealed an urgent need to address the lack of awareness of birth preparedness among rural women by doctors and nurses during routine antenatal visits, or community-level workers during home visits.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.