Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2016.v02i03.002

Year: 2016, Volume: 2, Issue: 3, Pages: 6-12

Original Article

Riti Tushar Kanti Sinha1 , Preeti Rai2 , Aniruna Dey3

Background: The goal of hemovigilance is to improve the safety and quality of blood transfusion services. An identification of adverse transfusion reactions (ATRs) will help to take appropriate steps to reduce their incidence and make blood transfusion safe. To determine the frequency and type of ATR that occurred in patients and reported to the blood bank in a rural hospital in central India.

Materials and Methods: A retrospective review of all transfusion reactions reported to the Blood Bank at Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sevagram between January 2015 and December 2015 was done. All the transfusion reactions were evaluated by the blood transfusion officer and classified using standard definitions.

Results: A total of 8121 units of whole blood and components were issued to various departments in the hospital. Total 15 transfusion reactions were reported to the blood bank following whole blood transfusion only (0.27%). The most common type of transfusion reaction among all the ATRs was allergic (0.19%), followed by febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions (0.036%). Not a single case of bacterial contamination was found in this study.

Conclusion: The frequency of transfusion reactions in our study was found to be 0.27%. This could be an underestimation of the true incidence because of underreporting as well as due to the management of few cases by the treating clinician itself. Rational use of blood, improving storage conditions, bedside monitoring of transfusion and documentation of adverse events will help in improving transfusion safety. It is the joint responsibility of the blood transfusion consultant and their clinical counterpart to create awareness about safe transfusion services so that proper hemovigilance system can be achieved to provide patient care.

KEY WORDS:Adverse transfusion reactions, hemovigilance, whole blood transfusion.

Transfusion of blood products is a double-edged sword and should be used judiciously. Improvements in donor screening and transfusion transmissible diseases testing procedures have led to a decrease in the hazards and risks that are associated with transmission of the infectious diseases associated with blood transfusion.

However, the risks of non-infectious complications have become more apparent. These non-infectious complications called as adverse transfusion reactions (ATRs) can either be acute in nature or follow a delayed course.[1]

Knowledge of these ATRs helps not only in their easy identification and management but also it alerts us to prevent its occurrence by taking precautionary and adequate measures. The lack of proper and strict hemovigilance systems throughout the country makes it difficult to assess the true and actual incidence of these reactions.[2]

The incidence of acute blood transfusion reactions is estimated to be 0.2-10% and is responsible for mortality in 1 per 250,000.[3] The commonly encountered blood transfusion reactions include acute ABO hemolytic reactions, allergic reactions, anaphylactic reactions, bacterial contamination, and febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction (FNHTR). At times, the prevailing disease condition in the transfusion recipient makes the definite diagnosis of transfusion reactions even more difficult.[4]

The term hemovigilance was coined in France in the early 1990’s. Since its inception, this system has been developed, adopted internationally, and now an integral part of transfusion practices. This is a systemic surveillance of ATRs and it aims to improve the safety of the transfusion process.[5] Due to the underreporting oftheminoradverseeventsbythemedicalstaff,the actual prevalence of these ATRs is not known.

The primary aim of Hemovigilance Programmes in India is to improve the transfusion safety and quality by collecting, analyzing and disseminating information on a common arena of serious adverse reactions due to transfusion of blood and blood products. It is also a continuous process of data collection and analysis of blood transfusion related adverse reaction to investigate their cause and outcome and prevent their occurrence or recurrence.

This study was undertaken to detect the incidence of transfusion related adverse events that occurred in patients who were hospitalized and required transfusion at a rural hospital in central India.

A retrospective review of all transfusion reactions that were reported to the blood bank at Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, Maharashtra, over a period starting from January 2015 until December 2015 was done. All the reactions were evaluated by the treating clinician as a part of transfusion reactions work up and the blood transfusion consultant. An algorithm was already provided to the medical staff in the ward on how to proceed with clinical and laboratory investigations whenever any transfusion reaction occurred.

The details were noted on a transfusion reaction form. In the case of any transfusion reaction, the following workup was done. Pre-transfusion data that were collected included patient’s central registration number, ABO and Rh group of the patient, type of blood product transfused, donor number and blood group, date and time of starting transfusion, patient’s vital signs, blood bag number, sample tube number, and any history of previous transfusion given to the patient.

Post-transfusion data included date and time of stopping transfusion, approximate volume of blood transfused, type of reaction, patient’s vital signs, and volume of urine passed. As part of the routine transfusion reaction evaluation, the patient’s blood sample and blood component(s) were checked for clerical errors. Any abnormal mass or clot if present in the blood bag was also checked for. Furthermore, the serum or plasma in a post-reaction blood sample was inspected for any evidence of hemolysis and compared with a pre-reaction sample, if available. The tests performed after the occurrence of transfusion reaction were patient’s ABO and Rh group on pre- and post-reaction samples, donor’s ABO and Rh group, patient and donor re-cross matching on pre- and post-reaction samples (minor and major cross matching), direct antiglobulin test on patient’s pre-and post-reaction samples, complete blood picture and peripheral blood film examination on post-reaction sample, patient’s urine detailed report and blood bag culture.

The serum or plasma in a post-reaction blood sample was inspected for any evidence of hemolysis and compared with a pre-reaction sample. Urine examination was carried out for every case of transfusion reaction. Urine examination for hemosiderin was also done to rule out any hemolytic cause. Specific tests to determine allergens like serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) and IgA are not always done in cases suspected of allergic reactions. Five out of the 11 cases (45.45%) of allergic reaction had an absolute eosinophil count greater than 5 × 109/L indicating hypereosinophilia.

Blood grouping and Rh type of the donors and recipients sample was done by both, forward, and reverse grouping. Anti A, anti-A1, anti B, anti D sera were used for performing the blood groups.

Other investigations included serum bilirubin, plasma hemoglobin, serum haptoglobulin, urine gross, and microscopic examinations for hemosiderinuria. Transfusion reactions occurring during or within 4 h after transfusion were evaluated. Based on the clinical features experienced by the recipient and laboratory parameters, these reactions were classified by standards and recognized definitions defined by American Association of Blood Banks.[6]

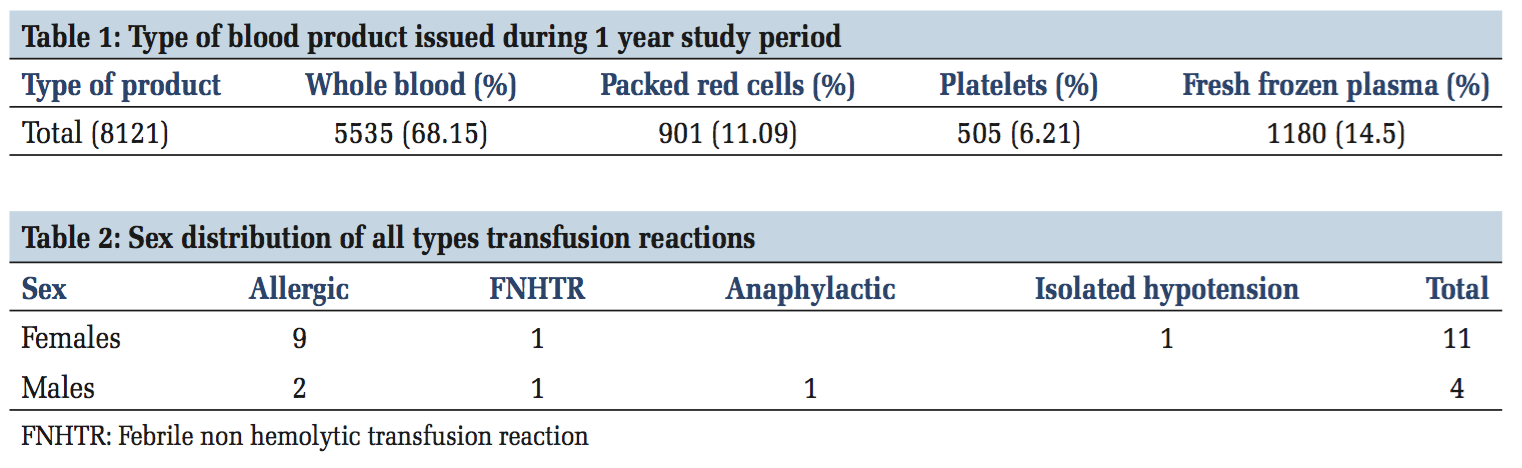

A total of 8121 units of whole blood and components were issued to various departments in the hospital during the 1-year study period (Table 1). These comprised whole blood (5535 [68.15%]), packed red blood cells (901 [11.09%]), fresh frozen plasma (1180 [14.5%]), and platelets (505 [6.21%]). The total number of transfusion reactions reported to our transfusion service during the study period were 15/5535 (0.27%) of whole blood transfusions.

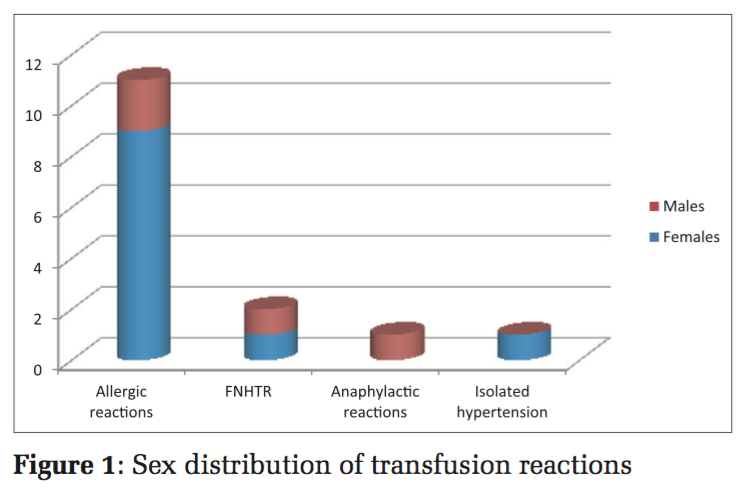

There were 11(73.3%) females and 04(26.7%) males who had experienced a transfusion reaction (Figure 1 and Table 2).

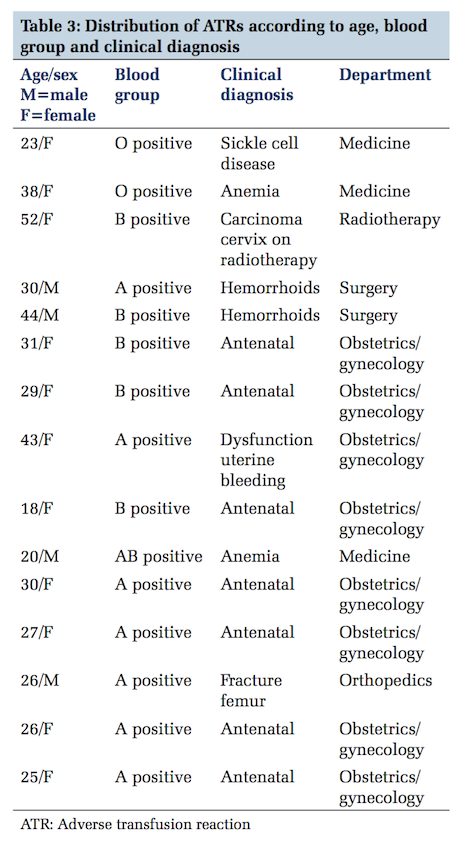

The age range of all these ATR spanned between 18 and 52 years (Table 3).

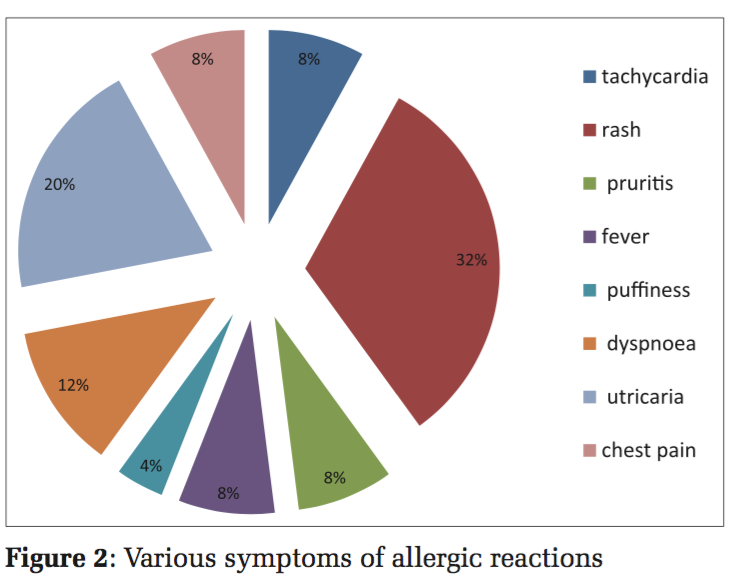

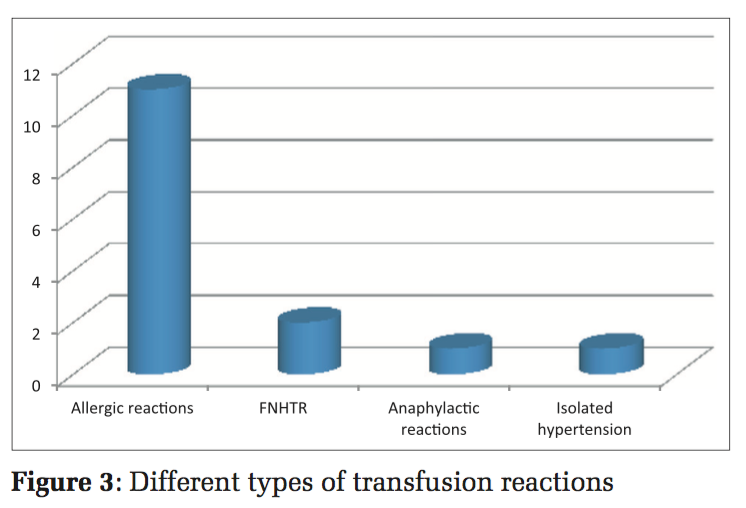

The signs and symptoms encountered in all the various reactions included tachycardia (n = 02 [13.33%]), rash (n = 08 [53.33%]), pruritis (n = 02 [13.33%]), fever (n = 02 [13.33%]), puffiness (n = 01 [6.66%]), dyspnea (n = 03 [20%]), utricaria (n = 05 [33.33%]), and chest pain (n = 02 [13.33%]) (Figure 2). All the signs and symptoms were reported within 4h of starting the transfusion. All the transfusion reactions occurred with whole blood. Among the 15 transfusion reactions confirmed by the blood transfusion consultant, there were allergic reactions (n = 11/15 [0.19%]), FNHTR (n = 02/15 [0.036%]), anaphylactic reactions (n = 01/15 [0.018%]), and isolated hypotension (n = 01/15 [0.018%]) (Figure 3).

The total number of transfusion reactions reported, in our study, were 15/5535 (0.27%). Acute reactions occurring within 4 h of starting transfusion was 14/15 (93.33%). One delayed type of transfusion reaction was seen. The mean volume of blood

transfused when the transfusion reaction occurred was 120 ml.

Maximum number of ATRs were seen in blood Group A followed by B, O and AB (Table 3).

Past history of transfusion was present only in two females (sickle cell disease - 1, radiotherapy for carcinoms cervix - 1 and two males haemorrhoids - 2) (Table 3).

At times the clinical diagnosis is of value in cases of ATR. In cases of sickle cell disease packed red cells are used instead of whole blood. In our study, there was a single case of sickle cell disease, where whole blood was used. Also in cases of patients on radiotherapy, packed red cells or leukoreduced blood should be used to avoid ATRs, especially FNHTR.

The most common type of transfusion reaction among all the ATRs was allergic (0.19%), followed by FNHTRs (0.036%). Anaphylactic and isolated hypotension (0.018%). Not a single case of bacterial contamination or acute hemolytic reaction was found in the present study (Figure 3). In this study, there were no transfusion-related deaths.

Adverse reactions are unprecedented risks that are associated with allogenic blood transfusions. this study conducted that information was collected regarding the various transfusion reactions from the cases that were referred to the blood bank. Evaluation was done on the basis of clinical examination, laboratory workup, and predefined protocol.

There are a few factors that signify that the number of transfusion reaction that is reported to the blood bank may not be the actual number. Patients receiving multiple transfusions, issued blood products that are unused, blood products not returned to the blood bank or discarded may be the causes of underreporting of these transfusion reactions. Underreporting of the actual number of transfusion reactions may also occur.[6]

First hemovigilance surveillance system was implemented in France in 1994 as a part of mandatory reporting as required by updated French regulation. Serious hazards of transfusion (SHOT) were in established United Kingdom shortly after 1996 as voluntary reporting. In the United Kingdom and Ireland, 366 reports of deaths or major complications of transfusions were reported as a part of SHOT initiative. The most common adverse (52%) event was giving wrong blood to the recepients.[1]

Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission in collaboration with National Institute of Biological has launched a Hemovigilance Programme of India on 10th December 2012. The main objectives of the program are to track the adverse reactions/events and incidences associated with transfusion of blood and blood product and to help identify trends, recommends best practices and interventions required to improve patient care and safety, while improving the overall health care.[7] Transfusion reactions present as adverse signs and symptoms occurring in patients during or after transfusion of blood components. These can be of the following types: (1) Immune reactions, (2) non immune reactions, (3) immediate reactions, (during or within few hours of transfusion), and (4) delayed reaction (days or weeks after the transfusion).

The hemolytic transfusion reaction (acute and delayed), FNHTR, allergic/anaphylactic reaction, alloimmune reactions, transfusion-related acute lung injury, and post-transfusion purpura are all types of immune reactions.

In this study, the highest number of ATR was found in blood Group A followed by B. In this study, the frequency of transfusion reactions was found to be 0.27%. In a similar study done by Bhattacharya et al.,[8] the prevalence of transfusion reactions was found to be 0.18%, whereas Sidhu et al.[9] and Kumar et al.[2] found a rate of 0.28% and 0.05%, respectively. The prevalence rate of our study matched with Sidhu et al.[9] The difference in rates of prevalence is due to factors related to underreporting as reported in a study by Narvios et al.[6]

In our present study, females were more affected than males similar to the study by Sidhu et al.[9] However, Kumar et al.[2] in their study found males to be more affected than females.

The definition of an allergic reaction may vary from patients having the presence of only fever or urticaria to the presence of wheezing and angioedema. Specific tests to determine it like serum IgE and IgA are not always done. Among non- hemolytic transfusion reactions allergic reactions occur most frequently. In our study, 5 out of the 11 cases of allergic reaction had hypereosinophilia. Other than allergies, dermatological disorders, parasitic infections, bacterial infections, collagen vascular diseases, side effects of medications, and myeloproliferative diseases can also lead to an increase in eosinophil count. These conditions also need to be ruled out.

Allergic reactions to unknown components in donors’ blood are common. Along with mast cell stimulation, immunologically active undigested or digested food allergens in donors plasma or less commonly antibodies from an allergic donor can act as triggering events in allergic reactions. These usually present as urticaria or erythematous lesions and respond to antihistamine therapy. Anaphylactic reactions were categorized as those having systemic symptoms including hypotension and/or loss of consciousness and/or shock.[8]

In our study, the highest incidence of transfusion reactions was found to be of allergic in nature. The overall incidence of allergic reactions was found to be 0.19% in this study. In all these cases, transfusion of whole blood was implicated. Sidhu et al.,[9] Kumar et al.,[2] and Domen and Hoeltge[10] found an incidence of allegic reactions 0.11%, 0.028%, and 0.02%, respectively, in their studies.

The overall incidence of FNHTR was found to be 0.036% in the present study. FNHTR was defined as “a body temperature rise of >1°C occurring in association with transfusion and without any other explanation.” Rigors and other symptoms in the absence of fever were also included as FNHTR.[11]

Differing from our study, Khalid et al.[12] showed that febrile non-hemolytic reaction (0.03%) was the most frequent transfusion hazard followed by allergic reactions (0.02%). Kumar et al.[2] and Bhattacharya et al.[8] found an incidence of 0.04% and 0.114% of FNHTR, respectively. This variation in the frequency of FNHTR among different studies can be attributed to variations in reporting, therapeutic interventions and at times due to many cases that are not reported to the blood bank.

Since 1960 whole blood has been separated into it components so that full utilization of the entire blood product can be made. However, little attention has been paid to the leukocytes present in the various blood components. The removal of leukocytes from various blood components can minimize the risks associated with these contaminating leukocytes. The most common outcome is FNHTR, human leukocyte antigen alloimmunization, and platelet refractoriness observed in multi-transfused patients. Leuckdepletion and leukoreduction are terms used colloquially and interchangeably but have quite different meanings. These concepts were introduced way back in 1920 by Fleming. Leukoreduction means the removal of leukocytes by gross removal techniques. Leukodepletion is the removal of leukocytes with the help of specific filters and devices.[13]

The overall risk of FNHTR has reduced to 0.12% in non leukoreduced to versus 0.08% in leukoreduced blood products.[10]

Hence, with the wider use of leukoreduced blood products, the incidence of FNHTRs, Cytomegalovirus transmission and platelet refractoriness has decreased.[2]

Finally, underreporting by medical staff could have underestimated the number of ATRs in our study.

The overall incidence of anaphylactic reactions was found to be 0.018 in our study. Sidhu et al.,[9] Kumar et al.[2] and Domen et al.[10] found incidence of anaphylactic reactions 0.11%, 0.003% and 0.003% respectively in their studies.

The incidence of isolated hypotension was found to be 0.018% in our study. Khalid et al.[12] had prevalence of 0.001% of isolated hypotension in their study.

Despite vigorous screening of donors, bacterial contamination still remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality.

Bacterial contamination is the contamination of the blood product detected by a positive culture of the blood product resulting in infection of the recipient.

The sources of bacteria are usually bacteria from venepuncture site of due to lacunae in the maintenance of aseptic techniques while preparation of the various blood components. In the present study, there was no incidence for bacterial contamination that is very rare.

Risk factors associated with acute ABO incompatible hemolytic reactions were mainly technical or clerical errors. Clerical errors include misidentification of the patient or the recipient. Technical errors included errors in blood grouping of donor or patient’s blood or errors in cross matching. Baele et al. reported bedside transfusion errors occur in 12.4/1000 transfusions.[14] Good enough estimated that the administrative errors were the most serious risks leading to acute ABO incompatible hemolytic reactions.[15] In our study, there was not a single case of acute ABO incompatible hemolytic reactions.

The frequency of transfusion reactions in this study was 0.27% in whole blood transfusions. This reaction rate can be underestimation of true incidence, because of underreporting which can be improved by the implementation of the hemovigilance system. This study shows the importance of rational use of blood and its components, improving storage conditions, bedside monitoring of transfusion and documentation of adverse events and implementation of the hemovigilance system, thus helping to improve transfusion safety.

Proper monitoring and knowledge of the signs and symptoms of the ATRs help in the early identification of these reactions and hence timely management and reporting.

It is the joint responsibility of the blood transfusion consultant and their clinical counterpart to create awareness about safe transfusion services so that proper hemovigilance system can be achieved to provide patient care. This study is an effort toward this direction.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.