Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2021.v07i01.007

Year: 2021, Volume: 7, Issue: 1, Pages: 38-42

Original Article

Trupthi Gowda1, M Rajini2

1Associate Professor, Department of Microbiology, The Oxford Medical College, Hospital and Research Center, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India,

2Head, Department of Microbiology, The Oxford Medical College, Hospital and Research Center, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. M. Rajini, Department of Microbiology, The Oxford Medical College, Hospital and Research Center, Bengaluru - 562 107, Karnataka, India. Phone: +91-9880920291. E-mail: [email protected]

Background: Occurrence of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) in 2–11% of pregnant women is a major predisposition to the development of pyelonephritis, which is associated with significant maternal and fetal complications.

Aim : The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of ASB among pregnant women, to report the most common organisms causing ASB, along with their antibiotic sensitivity patterns.

Materials and Methods A total of 250 asymptomatic pregnant women were screened for ASB by urine culture by standard microbiological procedures and the antibiotic sensitivity patterns recorded.

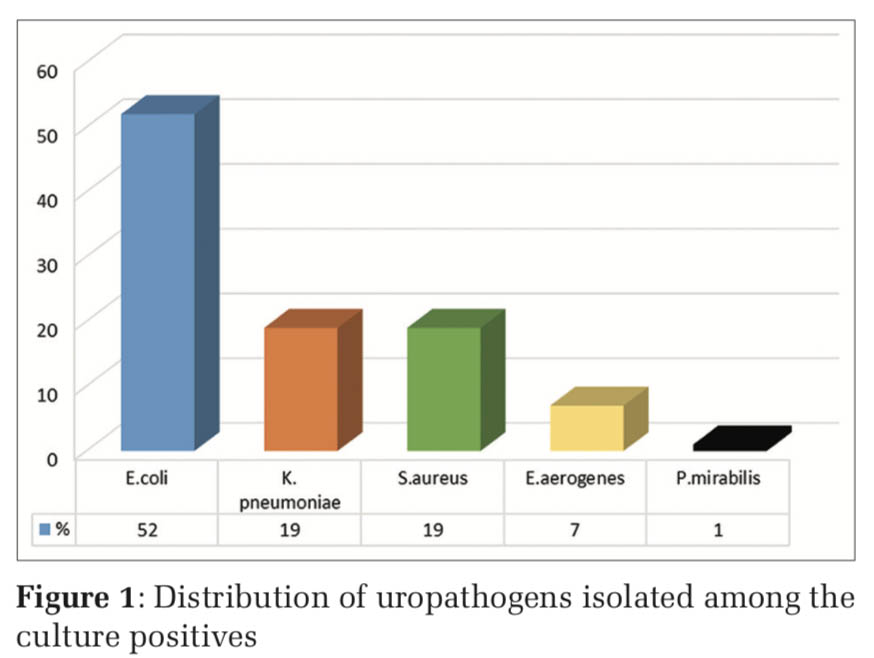

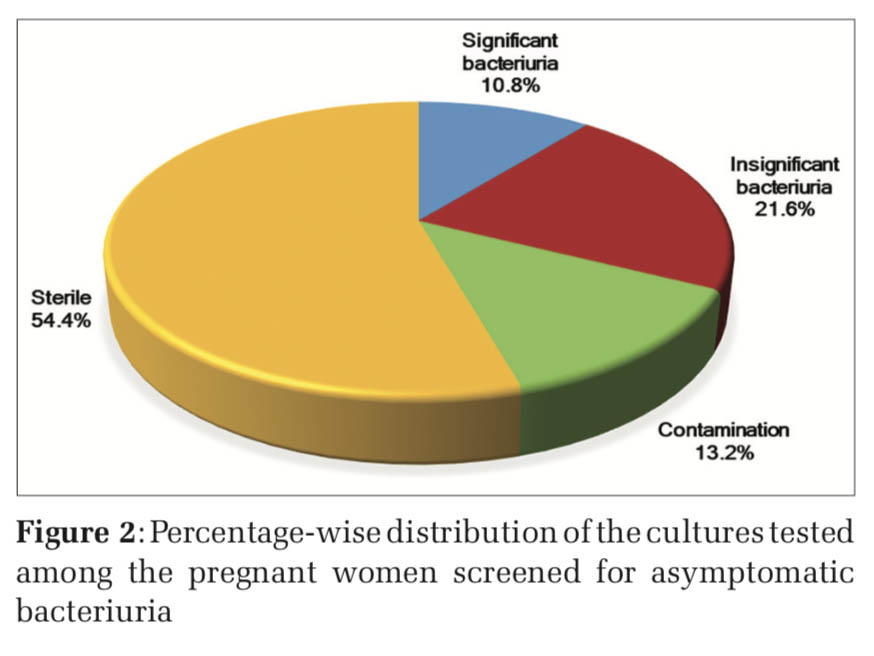

Results Of the 250 pregnant women screened, 27 (10.8%) had ASB. The most common organism was Escherichia coli (52%) followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus (19%). Majority of the uropathogens were found to be sensitive to nitrofurantoin (81%) and ciprofloxacin (63%).

Conclusions: The high prevalence of ASB among pregnant women (10.8%) in our center demands the need for routine screening of the pregnant women and treat them appropriately, to reduce the risk of complications associated with ASB.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common illnesses for patients to seek medical help. UTI affects all age groups and gender but are frequently encountered bacterial infections among women due to the short urethra, anatomical position of the vagina, and pregnancy [1]. UTIs are of two types, symptomatic and asymptomatic. Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is common among the women of the reproductive age. ASB is defined as presence of bacteria in significant numbers (>105 bacteria/ml) within the urinary tract with absence of symptoms of UTI (fever, dysuria, increased frequency, and burning micturition) [2]. The prevalence of ASB among pregnant women varies from 2% to 11% [3]. Detection of ASB becomes important as undetected ASB leads to symptomatic infection further causing acute pyelonephritis in 30–40%, preterm labor, low birth weight infants, and perinatal death of fetus [4]. A large scale study showed that screening and treating pregnant women with ASB reduced the risk of complications [5]. There are several screening tests to diagnose UTI, but urine culture is the gold standard screening technique for ASB [4]. The isolated organisms and their sensitivity patterns vary geographically [2] (Figure 1).

The objective of our study was to know the prevalence of ASB among antenatal cases, identify the most common organism causing ASB, and report the antibiotic susceptibility patterns.

This descriptive observational study included 250 pregnant women who attended the antenatal clinic of obstetrics and gynecology department at a tertiary care center in South India, over a period of 6 months (September 2018–February 2019). Pregnant women with symptoms of UTI (fever, increased frequency, dysuria, urgency, and burning micturition), any history of antibiotics usage in the previous 2 weeks, pregnancy induced diabetes or hypertension, pyrexia of unknown origin, and known congenital anomalies of urinary tract were excluded from the study. After taking an informed consent from the subjects, the demographic details, medical, and obstetrics history were obtained using questionnaires. The study was conducted after approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee.

Sample collection, processing, and interpretation The subjects were instructed to collect clean catch mid-stream urine into a sterile wide mouth screw- capped container. The samples were transported to the microbiology laboratory for processing within an hour of collection. The samples were cultured onto 5% sheep blood agar, MacConkey agar by standard loop method. The culture plates were incubated aerobically at 370 C overnight. After 24 h, interpretation of bacterial growth was done based on colony forming units as follows: equal to or >105 CFU/ml was considered significant, < 105 CFU/ml was considered insignificant and mixed growth of 2 or more isolates were considered to result from contamination. It was interpreted as sterile if no growth was obtained, even after 48 h of incubation. Significant bacterial isolates were identified by standard microbiological procedures [6] and subjected for antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing The standardized Kirby–Bauer’s disc diffusion method of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute was used for antibiotic sensitivity testing and the results interpreted accordingly [7]. The antibiotics tested were ampicillin, amoxyclav, cotrimoxazole, cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftriaxzone, ceftazidime, and cefepime), ciprofloxacin, nitrofurantoin, norfloxacin, carbapenems (meropenem, imipenem), erythromycin, clindamycin, linezolid, penicillin, and high-level gentamicin.

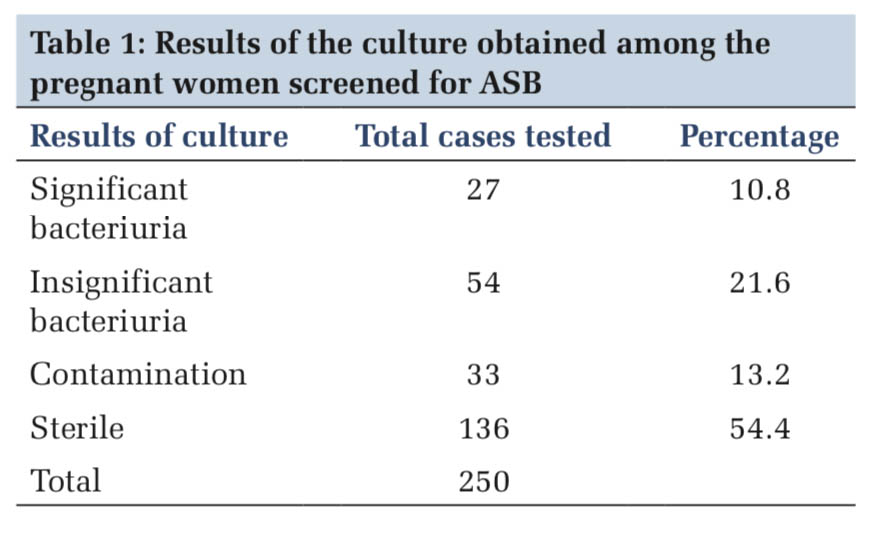

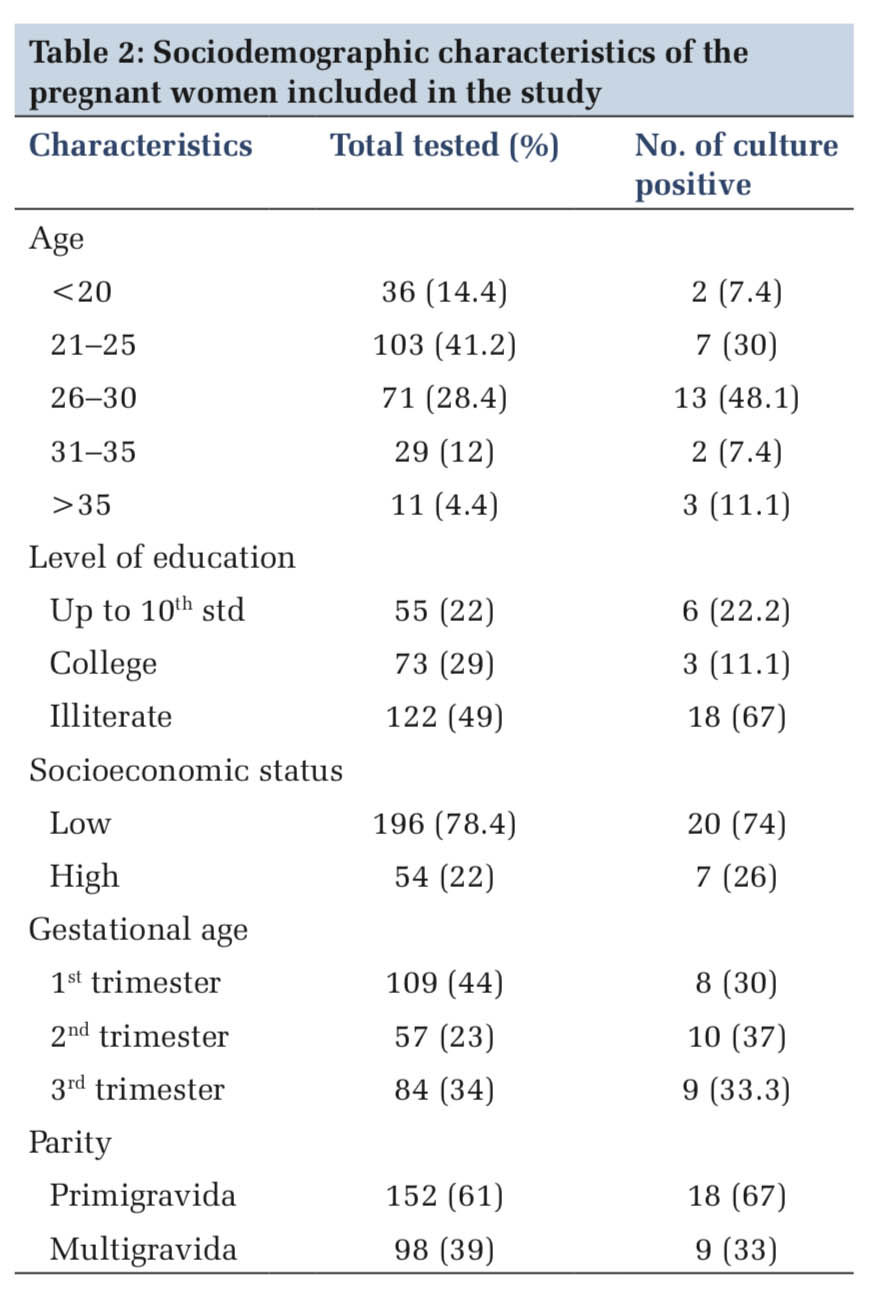

Of the 250 urine samples screened for ASB, 27 samples were reported positive for significant bacteriuria giving a prevalence of 10.8% (Table 1 and Figure 2). The sociodemographic details of the study subjects are shown in Table 2. Majority of the pregnant women with significant bacteriuria were in age group of 26–30 years (48%) followed by 21–25 years (30%). Most of the study subjects belonged to the low socioeconomic background (78%) and were not literate (49%), similarly the culture positive cases in these groups were to the tune of 74% and 67%, respectively. Our study findings showed that majority of the culture positive cases were recorded in the 2nd trimester (37%) followed by 3rd (33%) and 1st trimester (30%). Significant bacteriuria was found to be more common among primigravidae (67%) than multigravid individuals (33%). The age, social class, level of education, gestational age, and parity did not show any statistically significant differences.

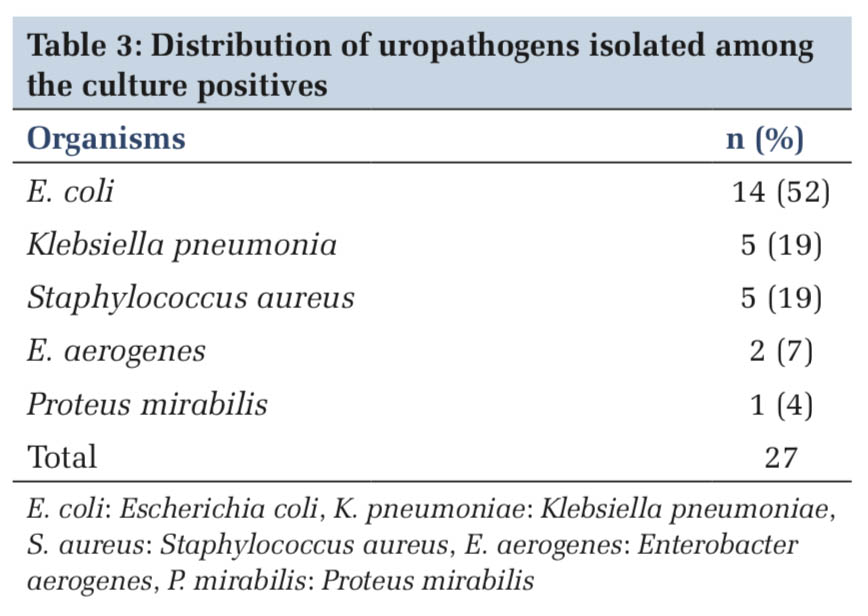

Table 3 shows the frequency distribution of the uropathogens isolated. E. coli (52%) was the most common bacterium detected in culture followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (19%) and Staphylococcus aureus (19%).

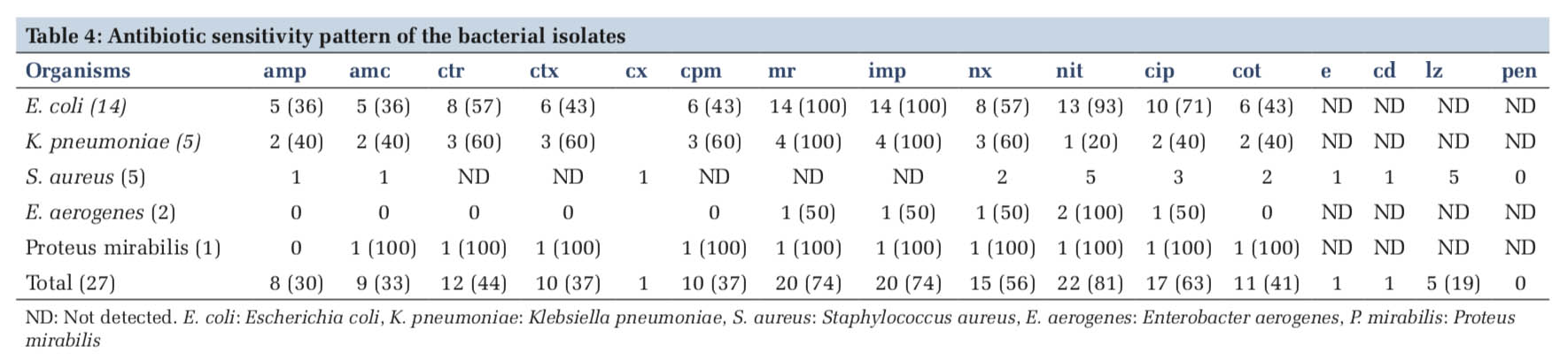

The antibiotic sensitivity pattern of the bacterial isolates is represented in Table 4. With respect to E. coli as it was the most frequently isolated uropathogen, it was found to be sensitive to carbapenems (100%), followed by nitrofurantoin (93%) and ciprofloxacin (71%). It showed least sensitivity to Ampicillin and amoxycillin-clavulinic acid combination (36%). Among the other gram negative organisms, K. pneumoniae also showed 100% sensitive results for carbapenems and a varied sensitivity to the other panel of antibiotics tested. We had only one isolate of proteus mirabilis, which was a completely sensitive strain. Of the five isolates of S. aureus, four were Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (80%) and one was methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) (20%). All the five isolates were recorded as sensitive to linezolid (100%). Overall, majority of the uropathogens were found to be sensitive to nitrofurantoin (81%) and ciprofloxacin (63%).

In this study, the prevalence rate of ASB among the study subjects was 10.8%, which correlates well with the global prevalence of 2–11%. Reports from studies conducted in different regions of the world [8-11] are in concordance with our findings. However, the prevalence rates are lower in reports from Khan et al., Onu et al., and Imade et al. [12-14]. The variation in the prevalence rates among the studies could be due to differences in the study participants, socioeconomic status, geographical location, and more so with the methods of screening tests. The highest prevalence of ASB was seen among women of age group 26–30 years followed by 21–25 years, this report agrees with the observations made by Sujatha and Nawani and Elzayat et al. [2,11]. This observation can be explained; an early exposure to sexual intercourse could lead to damage of the urethra and thereby causing transfer of bacteria from the anal region into the urinary bladder [15]. In analyzing the study subjects by their trimester and parity, ASB was highest in pregnant women of 2nd trimester (37%) and among the primigravidae (67%), which is in consonance with the observations of a study from West Bengal, India (43% and 52%) [16].

E. coli was the most common uropathogen isolated followed by K. pneumoniae and S. aureus. Our findings are similar to the reports of other studies conducted in different regions who have reported E. coli as the predominant uropathogen [1,3-5,9]. However, this contrasts with the observations of Onu et al. and tadesse et al who reported S.aureus and CONS, respectively, as the most prevalent uropathogen causing ASB [13,17]. The predominance of E. coli causing UTI could be due to the fact that it comprises as the commensal flora of the rectal region, and also, the close proximity of the urethra to the anal opening in the female explains the fecal contamination of the urinary tract [18]. Moreover, the distension of the abdomen in the pregnant women makes cleaning of the anal region difficult after defecation or urination. During pregnancy stasis of urine is common due to the gravid uterus, further facilitating the persistence and multiplication of E. coli [19,20]. The other organisms isolated in the study included Enterobacter spp and Proteus spp, which are less likely associated with causing UTI [21].

Antibiotic sensitivity patterns vary from one region to another. The multi-drug resistant organisms are prevalent in every country with a slight variation in the extent and severity of the problem. The single and most crucial factor being: misuse or overuse of antibiotics. In this study, the isolates were 100% sensitive to carbapenems. Most of the uropathogens were susceptible to nitrofurantoin (93%) followed by ciprofloxacin (71%). Isolates identified by Enayat et al. and Dash et al. also showed high sensitivity to these drugs [1,9]. On the other hand, a lower sensitivity of 37% for cefuroxime and cefepime and 44% for ceftriaxzone was observed in our study. This correlates well with a study from Puducherry, India, but differs from those of Celen et al. and Sujatha and Nawani who reported a sensitivity ranging from 86% to 96% for cephalosporins [2,3,22]. It is worth mentioning that use of cephalosporins for the treatment of UTI in pregnancy is relatively safer than fluoroquinolones, which are generally avoided unless there is an indication [23]. The isolates showed considerable susceptibility to ampicillin and amoxicillin-clavulinic acid combination (36%) which is similar to the findings of Oli et al. [5]. Ampicillin was regarded as safe in empirical treatment of UTI among pregnant women, but the indiscriminate use of this drug has led to the emergence of resistance.

A total of 27 isolates GNB accounted for 81% and GPB accounted for only 19%, with S. aureus being the only Gram-positive organism isolated (four were MRSA and one MSSA), which is similar to studies from Kolkata and Southern Ethiopia [8,17]. This is in contrary to study by Dash et al. who isolated Enterococcus faecalis as the most prevalent Gram- positive organism after E. coli [9]. This reporting of sensitivity pattern will surely help the policy makers in determining the drugs to be administered for the treatment of ASB in this region.

The prevalence of ASB among pregnant women is 10.8%. The predominant uropathogens isolated were E. coli, K. pneumoniae and S. aureus which were found to be sensitive to carbapenems, nitrofurantoin, and ciprofloxacin. A reasonably high prevalence rate of ASB is associated with complications for mother and fetus, therefore periodical screening of pregnant women by culture and antibiotic sensitivity will avoid antibiotic abuse. At the same time, regular checkups by health-care workers should be performed to identify women with ASB and appropriately treated to reduce the same.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.