Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.v11.i3.25.109

Year: 2025, Volume: 11, Issue: 3, Pages: 312-320

Original Article

Nikhil Era1 , Mala Mukherjee2 , Shatavisa Mukherjee3

1Department of Pharmacology, Mata Gujri Memorial Medical College, Kishanganj, Bihar, India,

2Department of Pathology, Mata Gujri Memorial Medical College, Kishanganj, Bihar, India,

3Department of Clinical & Experimental Pharmacology, Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine, Kolkata, India

Address for correspondence: Nikhil Era, Department of Pharmacology, Mata Gujri Memorial Medical College, Kishanganj, Bihar, India.

E-mail: [email protected]

Received Date:17 March 2025, Accepted Date:17 June 2025, Published Date:14 November 2025

Background: Self-directed learning (SDL) and small group discussion (SGD) are two important learner-cantered methodologies in medical education and instil attributes desirable for a medical professional. The present study aims to compare SDL with SGD in prescription auditing skills in Phase II MBBS students.

Methods: This is a mixed-method study conducted at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Eastern India. One hundred Phase II MBBS students were enrolled, and they were randomized into groups on SDL and SGD. Following the induction week on prescription writing and critical appraisal, students were allocated into either SDL or SGD contact sessions. Perception of learning outcomes and teaching methods was determined before and after exposure to the intervention by perception surveys based on a validated questionnaire and case-based evaluations (CBE) and analysed with paired and unpaired t-tests; significance was taken at p < 0.05.

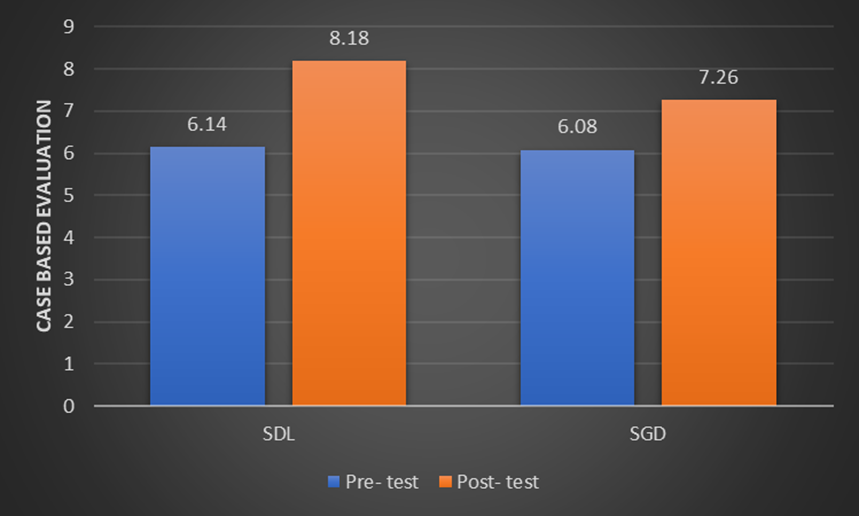

Results: CBE Scores CBE scores of both the cohorts improved significantly post-intervention. Mean score of SDL group was changed from 6.14 to 8.18 (p < 0.01) while that of SGD group changed from 6.08 to 7.26 (p < 0.01). Student Perceptions Participants from SDL group reported that they became more autonomous and enhanced their critical and analytic thinking. Whereas participants from the SGD group reported more positive outcomes in their collaboration, communication and problem-solving abilities. Perception scores of both the groups increased significantly post the intervention (p < 0.001).

Discussion: The students in SDL independently applied varied guidelines and other resources to output and, thus, demonstrated better prescription auditing skills compared to SGD. SGD facilitated group learning and discussion. Both were successful in developing critical thinking and applying it into practical clinical scenarios, which is the perfect goal of CBME.

Conclusion: SDL and SGD are effective educational strategies for training in prescription audits. SDL proves to be especially effective in allowing independent learning and critical decision-making; hence, it would probably hold promise as the method of choice to improve prescription auditing competencies within the medical curricula. Thus, with these findings, it will be further justified to perform research with larger cohorts

Self-directed learning (SDL) is an educational strategy where individuals take charge of planning, implementing, and assessing their learning activities.1 This approach nurtures autonomy, accountability, and assertiveness—qualities that are crucial for medical professionals who must engage in lifelong learning 2 and adapt to the constantly changing demands of healthcare. Recognizing this, medical educators are increasingly incorporating SDL into their teaching practices to prepare graduates for self-management and ongoing knowledge acquisition. 3 By emphasizing critical thinking, SDL not only aids information retention and recall but also sharpens decision-making skills, which are vital for a thriving medical career. 4

SDL is closely linked to self-regulated learning, a cyclical process where learners take control of their educational journey. This involves identifying knowledge gaps by assessing current understanding to determine areas needing further exploration, fostering introspection and self-awareness essential for growth. Developing actionable plans follows, with learners creating structured strategies that include setting goals, selecting resources, and organizing schedules. Monitoring progress is integral, as individuals evaluate their efforts and adjust strategies to address challenges and maintain focus. Finally, assessing outcomes allows learners to critically analyze their performance, identify successes, and recognize areas for improvement, reinforcing lifelong learning principles. 2

While SDL is inherently learner-centred, the role of educators and institutions in fostering an SDL-friendly environment cannot be understated. Faculty members serve as facilitators, empowering students to build essential skills for effective SDL. This includes guiding them in crafting insightful questions, encouraging the exploration of diverse learning resources such as peer-reviewed journals, case studies, and clinical guidelines, and offering constructive feedback to help learners refine their approaches and achieve their objectives.

Institutions, on the other hand, can support SDL by incorporating structured opportunities for self-directed activities into curricula, as seen in Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) frameworks globally. By creating a balance between structured guidance and independent exploration, educational programs ensure that students are well-prepared for the demands of lifelong learning

International accrediting bodies and professional organizations, such as the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), and the World Federation on Medical Education, recognize the importance of lifelong learning. 5, 6 These organizations have established standards requiring explicit instruction in SDL to ensure medical curricula foster continuous, SDL among students globally.

In India, the National Medical Commission (NMC) has introduced Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) for undergraduate medical students, a vision first outlined by the erstwhile Medical Council of India (MCI) in Vision 2015. Under the CBME framework, SDL is a core element, with designated hours allocated to SDL activities. For instance, the revised CBME curriculum for pharmacology includes 10 hours of SDL during the second phase of the MBBS program. This structured approach allows students to cultivate independent learning skills early in their education. However, contextual challenges, such as the traditionally teacher-centric secondary education system and misalignment between exam content and learning sessions, can affect SDL's efficacy.7 Adequate training and awareness for all stakeholders, especially Indian Medical Graduates (IMGs), are essential to maximize SDL's benefits. 8, 9

While lectures have traditionally been a fundamental part of medical education, their effectiveness in promoting meaningful, lasting learning is increasingly being scrutinized. Traditional lectures often result in surface learning, where students temporarily memorize information without truly understanding or applying it.10 Deep learning, in contrast, integrates new knowledge with prior understanding, enabling students to solve novel problems—an indispensable skill in the dynamic and complex field of medicine.

To address the limitations of traditional lecture-based teaching, small group discussions (SGDs) have emerged as a highly effective and complementary instructional strategy. SGDs typically involve small groups of three to five students, creating an intimate and interactive learning environment. This approach emphasizes collaborative activities, enabling students to actively engage with the material and with one another. Unlike passive lecture formats, SGDs facilitate meaningful dialogue, encourage the exchange of ideas, and provide opportunities for learners to clarify doubts in real time.

A hallmark of SGDs is their ability to foster inquiry and critical thinking. Students are encouraged to ask questions, explore different perspectives, and analyse complex scenarios, which enhances their problem-solving abilities. By focusing on the real-world application of concepts, SGDs help students bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical clinical practice.11, 12, 13, 14 For example, during case-based discussions, learners can connect newly acquired information with their pre-existing understanding and real-life experiences, making the learning process more relevant and impactful.

SGDs also align seamlessly with the goals of Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME), particularly for Indian Medical Graduates (IMGs). CBME emphasizes the development of essential competencies such as communication, teamwork, critical thinking, and adaptability. By fostering deep learning, SGDs support these objectives, helping students internalize concepts and apply them effectively in novel and complex medical scenarios.

In this context, the current study aimed to explore students' experiences with Self-Directed Learning (SDL) and evaluate the comparative effectiveness of SDL and SGDs during a case-based prescription audit activity. Prescription audit activities are particularly suited to such evaluations because they combine clinical reasoning, evidence-based decision-making, and practical skills. Investigating these teaching methods within this framework provides valuable insights into how different educational strategies can optimize learning outcomes and prepare medical students for the challenges of modern healthcare.

This mixed-method study, combining quantitative and qualitative assessments, was carried out at a tertiary care teaching hospital in eastern India. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval No. MGM/PRI-17/2024 dated 04/09/2023). Written informed consent was secured from all participants.

The sample size was determined using G*Power 3.1. Based on a pilot study (effect size = 0.8, α = 0.05, power = 0.95), a minimum of 46 participants per group was required. To account for attrition, 50 students per group (total 100) were enrolled.

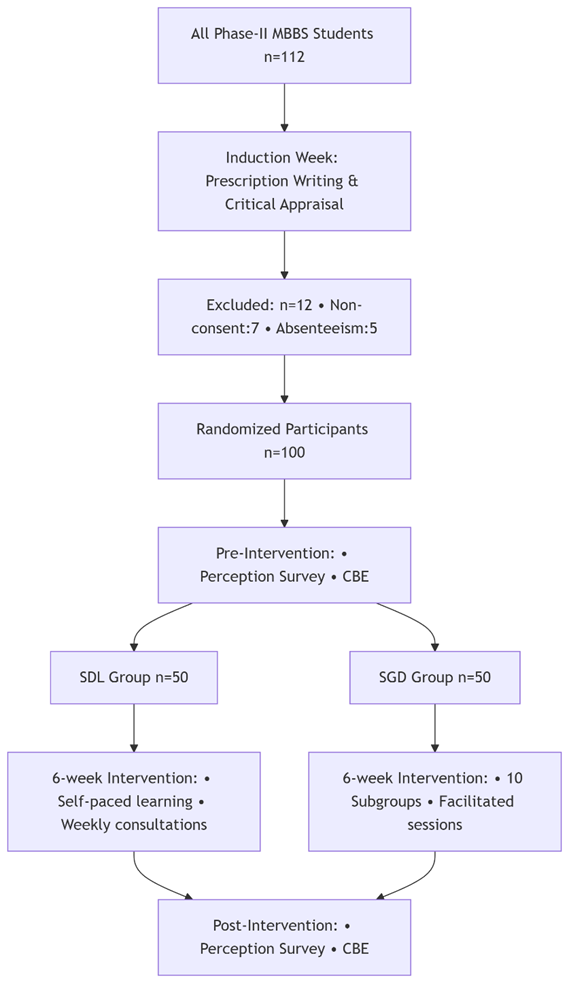

Phase II MBBS students (n=100) were randomized into two groups using a computer-generated random number table (1:1 allocation). Inclusion criteria: voluntary participation and attendance during the induction week. Exclusion criteria: prior formal training in prescription audits. Group allocation was concealed using sealed envelopes.

1. Self-Directed Learning (SDL Group (n=50):

Students received a curated resource package (NABH/WHO guidelines, case scenarios, and access to digital libraries).

A facilitator provided weekly 30-minute virtual consultations to address queries.

Tasks included independent analysis of 10 prescription sets via Google Forms.

2. Small Group Discussion (SGD Group (n=50):

Divided into 10 subgroups (5 students each).

Facilitators (trained faculty) conducted 90-minute sessions weekly.

Activities: role-playing, case analysis, and concept mapping.

Each subgroup presented findings, followed by peer feedback.

Scoring: Prescriptions were scored out of 10 using a validated rubric (Table 1) assessing completeness, drug interactions, guideline adherence, and rationale.

Process: Two blinded assessors evaluated pre- and post-intervention responses. Discrepancies were resolved by a third assessor.

A 10-item Likert-scale questionnaire (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) was administered via Google Forms.

Validation: Content validity was confirmed by three medical education experts. Pilot testing (n=30) showed Cronbach’s α=0.740 (SDL) and 0.763 (SGD).

The participants first underwent an induction session on the principles of prescription writing and critical appraisal, conducted as part of the routine curriculum through lecture with case-based discussion. After this session, the students were randomized into two groups using a random number table: as depicted in given flowchart (Figure 1 ).

Group 1: Self-Directed Learning (SDL)

Group 2: Small Group Discussion (SGD)

A survey questionnaire was developed to capture students’ perceptions of the SDL and SGD methodologies. The questionnaire underwent pilot testing and validation with a sample of 30 students from each group. It contained 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated "strongly disagree" and 5 indicated "strongly agree." The reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed through Cronbach’s alpha, with values of 0.740 for SDL and 0.763 for SGD, demonstrating acceptable reliability.

The validated questionnaire was then administered to both groups to gauge their initial perceptions of the teaching methods. Subsequently, a case-based evaluation (CBE) was conducted in which students were tasked with analysing and rewriting 10 prescription sets provided to them.

Following this, each group participated in contact sessions tailored to their assigned teaching method: SDL or SGD.

One month later, the survey questionnaire was re-administered to assess any shifts in perception. Additionally, another round of CBE was conducted to evaluate the students’ learning outcomes. The data collected from both groups were analyzed based on their CBE scores and perception ratings.

|

Parameter |

Max Score |

|

Completeness of prescription |

2 |

|

Adherence to guidelines |

3 |

|

Drug-drug interactions |

2 |

|

Rationale for therapy |

3 |

Data obtained from pre- and post-intervention tests were tabulated and statistically analysed. Descriptive measures were presented as mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentages as applicable. Pre- and post-intervention measures were compared within groups and between groups using paired and unpaired t-tests as applicable. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. All analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism 8.0.2, San Diego, CA, USA) and Microsoft Excel.

The study included 100 Phase II MBBS students.

In Group 1 (SDL), the mean pre-intervention CBE score was 6.14, which significantly increased to 8.18 post-intervention (p < 0.01). Similarly, in Group 2 (Small Group Discussion), the mean pre-intervention CBE score was 6.08, rising to 7.26 post-intervention (p < 0.01) (Figure 2).

Group 1 (SDL): Students reported that the SDL approach helped them identify their learning needs, establish short- and long-term goals, break down complex topics, and enhance their critical thinking and analytical skills. The perception scores for SDL showed a statistically significant improvement following the intervention (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

|

|

Pre-Intervention |

Post-Intervention |

P value |

|

Initiative to identify learning needs, set goals |

2.88 ± 0.99 |

3.6 ± 0.77 |

0.000 |

|

Ability to set short/long-term goals, breaking down complex topics |

3.24 ± 0.43 |

4.41 ± 0.57 |

0.000 |

|

Ability to choose from a variety of resources |

2.88 ± 0.84 |

3.88 ± 0.65 |

0.000 |

|

Actively apply knowledge to solve clinical problems, analyse case studies |

3.42 ± 0.57 |

3.74 ± 0.63 |

0.000 |

|

Assess my own progress, identify gaps in understanding, and adjust accordingly. |

3.54 ± 0.50 |

4.34 ± 0.65 |

0.000 |

|

Exploring different concepts beyond the standard curriculum |

3.34 ± 0.68 |

3.98 ± 0.68 |

0.000 |

|

Utilization of online platforms, digital libraries, and educational apps |

3.52 ± 0.57 |

4.06 ± 0.73 |

0.000 |

|

Engage in collaborative activities with peers |

3.92 ± 0.77 |

4.44 ± 0.70 |

0.000 |

|

Encourages to use of evidence-based practices and research for clinical decision-making |

3.42 ± 0.67 |

4.04 ± 0.72 |

0.000 |

|

Encourages to apply knowledge in real-world situations |

3.52 ± 0.57 |

4.08 ± 0.74 |

0.000 |

Group 2 (SGD): Students in the SGD group reflected on how this method promoted collaboration in identifying issues, generating hypotheses, and developing solutions. They noted improvements in critical thinking, decision-making, and the application and integration of knowledge. Additionally, students appreciated role-playing exercises for enhancing their communication and interpersonal skills. Activities such as critically evaluating research articles further enriched topic comprehension, interactive problem-solving, and deeper learning within specific fields. Perception scores for SGD also demonstrated a statistically significant improvement post-intervention (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

|

|

Pre-Intervention |

Post-Intervention |

P value |

|

Working collaboratively to identify the issues, generate hypotheses, and devise solutions, fosters critical thinking and decision-making skills |

3.36 ± 0.48 |

4.14 ± 0.45 |

0.000 |

|

Working in small teams on designed activities will promote application and integration of knowledge |

3.54 ± 0.75 |

3.98 ± 0.58 |

0.000 |

|

Role-playing can enhance my communication and interpersonal skills |

3.46 ± 0.50 |

3.86 ± 0.35 |

0.000 |

|

Engaging in critically evaluating research articles related to a particular field better enhances topic assimilation |

3.34 ± 0.47 |

3.52 ± 0.70 |

0.002 |

|

Collaboratively creating concept maps related to a specific topic reinforces understanding of relationships between different elements |

4.1 ± 0.78 |

4.52 ± 0.57 |

0.000 |

|

Assigning different viewpoints to small groups, helps research and present arguments |

3.44 ± 0.50 |

3.82 ± 0.59 |

0.000 |

|

Interactive problem-solving sessions encourages active discussion, ask probing questions, and guide toward evidence-based solutions |

3.26 ± 0.44 |

3.94 ± 0.61 |

0.000 |

|

Individual reflection, followed by paired discussion, and insight sharing with a larger group can help in collaborative learning |

3.5 ± 0.50 |

3.74 ± 0.66 |

0.000 |

|

Flipped classroom activities can help in better application of concepts, and addressing any questions or challenges. |

3.88 ± 0.65 |

4.38 ± 0.66 |

0.000 |

Self-directed learning (SDL) is a critical component of lifelong learning, and a key competency emphasized in medical school curricula. 1 A self-directed learner actively takes responsibility for their learning, demonstrating internal motivation to develop, implement, and evaluate their learning strategies.8, 15 Recognizing this, the National Medical Commission (NMC) mandates the inclusion of activities that cultivate SDL skills early in the preclinical years. 16

This study highlights significant improvements in prescription auditing skills among students in the SDL group. These students were able to incorporate a broader range of auditing parameters, such as drug-drug interactions (DDI), food-drug interactions (FDI), the number of antibiotics, and the use of vitamins and enzymes—areas often overlooked in traditional teaching methods.

Additionally, students in the SDL group were expected to familiarize themselves with audit parameters aligned with established frameworks, including NABH, CAHO, WHO-recommended core drug use indicators, the Prescription Audit Guidelines (PAG) by NRHM, and the CDC-recommended Medication Reconciliation Audit Tool Guidelines. This exposure enhanced their ability to apply prescription auditing skills across various platforms.

In contrast, students in the non-SDL group tended to focus only on parameters covered in lecture-based sessions, limiting their scope of understanding. This comparison underscores the effectiveness of SDL in broadening students' knowledge and skills in critical areas of medical practice.

Prescription and its auditing are conventionally taught by lecture, but if we incorporate SDL, it is expected that students will be able to include more Prescription Audit (PA) parameters that are otherwise missed.

Our study observed improved perceptions of SDL (measured on a Likert scale), with students gaining confidence in setting learning goals, identifying objectives, utilizing resources, and applying evidence-based knowledge. Perceptions of SGDs also improved, particularly in group dynamics, critical thinking, and role-playing for communication skills. Students noted that group work facilitated better understanding of complex topics through collaborative concept mapping.

Research supports SDL as a valuable tool for mastering basic medical sciences. Malcolm Knowles,1 a pioneer in adult education, describes SDL as a process where learners take initiative in diagnosing needs, setting goals, identifying resources, employing strategies, and evaluating outcomes, offering a solid framework for its integration into medical education.

SDL can be categorized into facilitated and self-paced learning.17 Facilitated learning involves guidance from a teacher or facilitator through discussions, virtual platforms, or email, providing structure while maintaining learner autonomy. Self-paced learning, on the other hand, depends entirely on the learner’s motivation, resourcefulness, and independence in selecting appropriate materials. A common SDL approach involves case-based scenarios with guiding questions, encouraging learners to find answers using recommended resources. 18 To excel in SDL, medical students must develop competencies such as critical thinking, self-evaluation, critical appraisal, teamwork, reflection, and self-awareness. These skills empower them to take charge of their learning, identify areas for growth, and continuously enhance their knowledge and professional capabilities. 19

Gerald Grow's Staged Self-Directed Learning (SSDL) Model 20 describes four progressive stages of learner self-direction, emphasizing the teacher's role in facilitating this development. In the Dependent Learner stage, students rely on the teacher as a coach who provides foundational skills through lectures, drills, and feedback. As Interested Learners, students begin goal setting and show initiative, with the teacher acting as a motivator through discussions and confidence-building activities. At the Involved Learner stage, students take ownership of their learning by identifying needs, setting goals, and planning actions, while the teacher serves as a collaborator, facilitating discussions and group projects. Finally, Self-Directed Learners are intrinsically motivated, independently setting goals, evaluating progress, and seeking resources, supported by teachers using inquiry-based and problem-based learning strategies. This model underscores the teacher’s pivotal role in adapting support to the learner's developmental stage.

Implementing and assessing SDL in medical education requires a structured, stepwise approach. Charokar et al.8 outline key steps: training facilitators, assessing students' readiness, selecting relevant topics, developing validated SDL modules, and sensitizing students to SDL, including group dynamics and search strategies. Additionally, necessary resources should be provided, student and faculty groups formed, SDL sessions implemented, and students assessed on knowledge, skills, and SDL competencies. The program should be evaluated using feedback from students, teachers, and stakeholders to ensure quality assurance.21 Facilitator training is critical, as they guide and support students, while readiness assessment ensures learners are motivated and prepared to take responsibility for their learning. These steps foster an environment conducive to effective SDL.

Implementing SDL effectively involves selecting relevant topics, developing validated modules, and equipping students with strategies for group dynamics and information search 19 Providing necessary resources, such as access to materials and technology, is essential. Forming collaborative student-faculty groups fosters interaction, while continuous evaluation and feedback help refine the SDL program to meet students' learning needs. The CBME framework, introduced by the National Medical Commission in 2019, emphasizes the importance of small group discussions (SGDs) in undergraduate medical education to develop reasoning, problem-solving, and teamwork skills.22 Common methods like problem-based learning (PBL), case-based learning (CBL), and team-based learning (TBL) promote learner-centred instruction by engaging students in solving clinical problems, applying theoretical knowledge, and fostering communication. 23

SGDs enhance practical problem-solving, evidence-based decision-making, and lifelong learning. 24 However, challenges such as time constraints, dominant participants, and off-topic discussions require skilled facilitation. 25 Facilitators guide the sessions by setting clear objectives, maintaining focus, encouraging participation, and resolving conflicts, ensuring effective learning and collaboration.

Faculty preparedness is crucial for the success of SGDs. Well-trained faculty are essential for guiding discussions, fostering critical thinking, and providing constructive feedback. Faculty development programs should focus on active learning methods, adult learning principles, facilitation skills, and adapting to diverse learning styles. 26 Resource allocation is another challenge in SGD implementation, requiring appropriate spaces, technology, and materials to create an effective learning environment 25 Institutions must invest in the necessary resources, including educational materials and technological infrastructure, to support SGDs. Limited access to technology, such as electronic health records and simulation tools, can hinder SGD efficacy. Tuckman’s model of group development (1996) 27 outlines five stages in team dynamics: forming, norming, storming, performing, and closure. Facilitators guide groups through these phases, ensuring smooth transitions from introductions to task performance, resolving conflicts, and maintaining focus during execution. Questioning plays a vital role in small group teaching, promoting a learner-centred approach. Frequent questioning helps facilitators assess individual learning needs, stimulate clinical reasoning, and encourage reflection. Open-ended questions encourage deeper understanding by prompting learners to integrate and apply knowledge.

Both SDL and SGD bring valuable benefits to medical education. Our study found that students who engaged in SDL showed measurable improvements in their prescription auditing skills compared to those who didn’t use this approach. This emphasizes the importance of adopting a comprehensive competency-based medical education (CBME) framework to help ensure that Indian Medical Graduates (IMGs) develop strong prescription auditing abilities. Moreover, these results suggest that SDL could be the preferred teaching method for prescription auditing in MBBS curricula. By encouraging students to take charge of their learning, we can better prepare them for the challenges they will face in their medical careers.

We express our heartfelt gratitude to our mentors, Dr Nachiket Shanker, Dr Sumeetha Lobo, Dr Mangala R., and Dr Sejil T.V., from St. John's Medical College, Bengaluru for their invaluable guidance, insightful suggestions, and generous support throughout the study.

Nil.

None Declared.

Approval for the study was granted by the Institutional Ethics.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.