Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2018.v04i03.004

Year: 2018, Volume: 4, Issue: 3, Pages: 20-25

Original Article

Snehlata R Hingway, Nilima D Lodha

Department of Pathology, Shri Vasantrao Naik Government Medical College, Yavatmal, Maharashtra, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Nilima D Lodha. AF1⁄2, Chandore Apartment, State Bank of India Square, Yavatmal – 450 001, Maharashtra, India. Phone: +91-9881888223. E-mail: [email protected]

Introduction: Nephrectomy is commonly carried out for renal neoplasms or benign conditions such as hydro- or pyonephrosis. A variety of neoplasms are incidentally detected in these latter benign nephrectomies and also in postmortem material. The objective of this study was to document the patterns and morphology of incidentally detected renal neoplasms, which may differ somewhat from those diagnosed preoperatively, and review the relevant literature.

Materials and Methods: This was a retrospective study carried out in a tertiary care hospital during a 5 years’ period (2013–2017). All kidney specimens, surgical or postmortem, where a neoplasm was found on histopathology and was not suspected preoperatively or antemortem respectively, were included in the study. The kidney specimens were processed according to standard procedures.

Results: Five neoplasms were incidentally detected in a total of 19 renal specimens received, four in surgical material, and one in an autopsy. All except the autopsy specimen were found in non-functioning kidneys, with hydro- or pyonephrosis. There were two renal cell carcinomas (RCCs), two pelvic squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), and one transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). The SCCs and one RCC were associated with renal calculi. The RCC detected postmortem was of the papillary variant, while the other one was a poorly differentiated variant. The TCC was not associated with calculi.

Conclusions: Numerous incidental neoplasms are found in surgical or medicolegal renal specimens, many associated with calculi and hydro- or pyonephrosis. The neoplastic element may be masked by the overwhelming benign lesion. Thorough sampling and a high index of suspicion are needed to detect these lesions. The sample size is too small to document any morphological pattern.

KEY WORDS:Incidental renal neoplasms, nephrectomy, post mortem.

Nephrectomy is a common procedure in surgical practice. Obstructive nephropathy, hydronephrosis, and chronic pyelonephritis are the most frequent type of nephrectomy specimens for non-neoplastic renal diseases in both adults and children. It is the treatment of choice in renal cell carcinomas (RCCs).[1,2] A variety of neoplasms are incidentally detected in nephrectomies carried out for non-neoplastic lesions,[3-6] as well as in postmortem material.[7] The objective of this study was to document the patterns and morphology of neoplastic lesions, usually found in nephrectomy specimens, received in a tertiary care hospital, where the neoplasm was not suspected preoperatively or antemortem. A review of the relevant literature available on this topic is also presented.

All patients who underwent nephrectomy for non-neoplastic indications and where a neoplasm was discovered incidentally on histopathological examination were included in the study. The other category included autopsy cases with renal neoplasm, not suspected antemortem. Hence, specimens were obtained surgically as well as by autopsy.

All specimens were grossed and sectioned in the standard manner,[8] fixed in 10% formalin, and sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

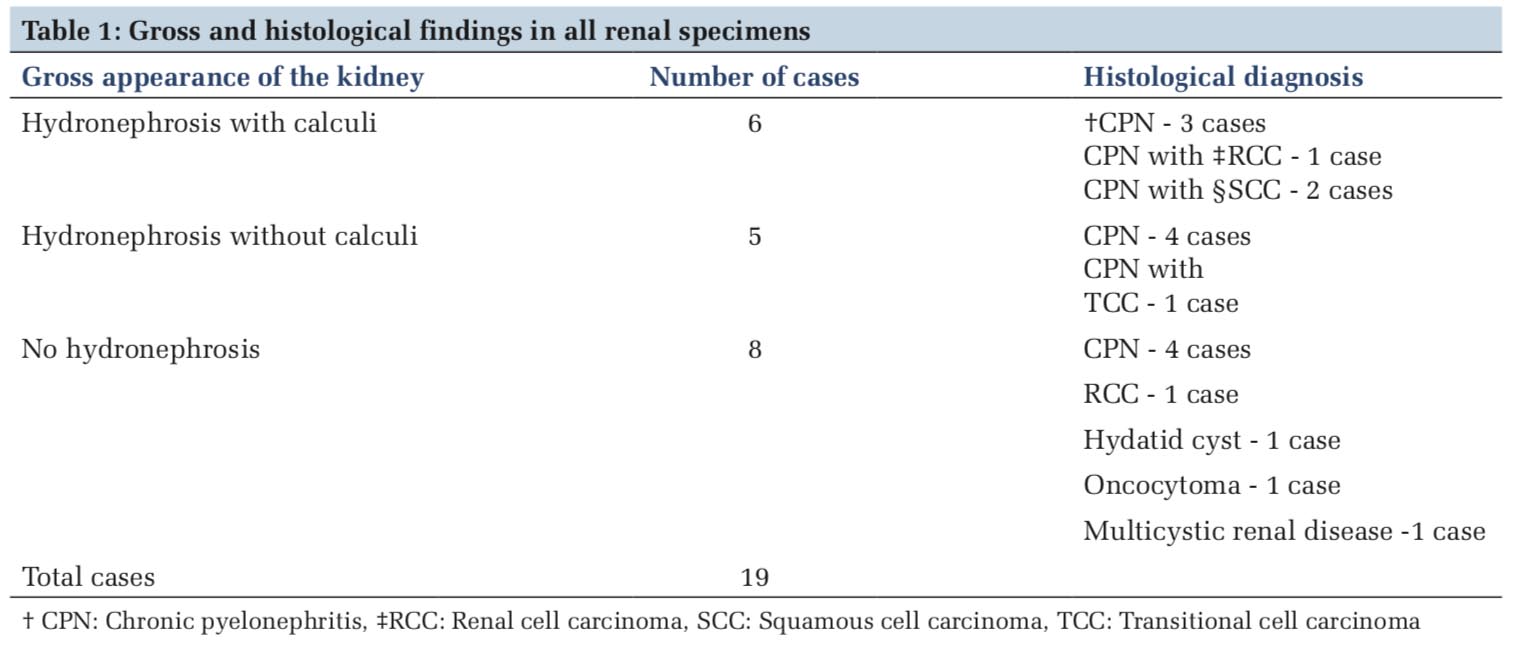

We received 18 nephrectomy specimens and one autopsy case in the 5 years’ period under consideration. The presence or otherwise, of hydronephrosis, with or without calculi and the respective histological diagnosis are tabulated in Table 1.

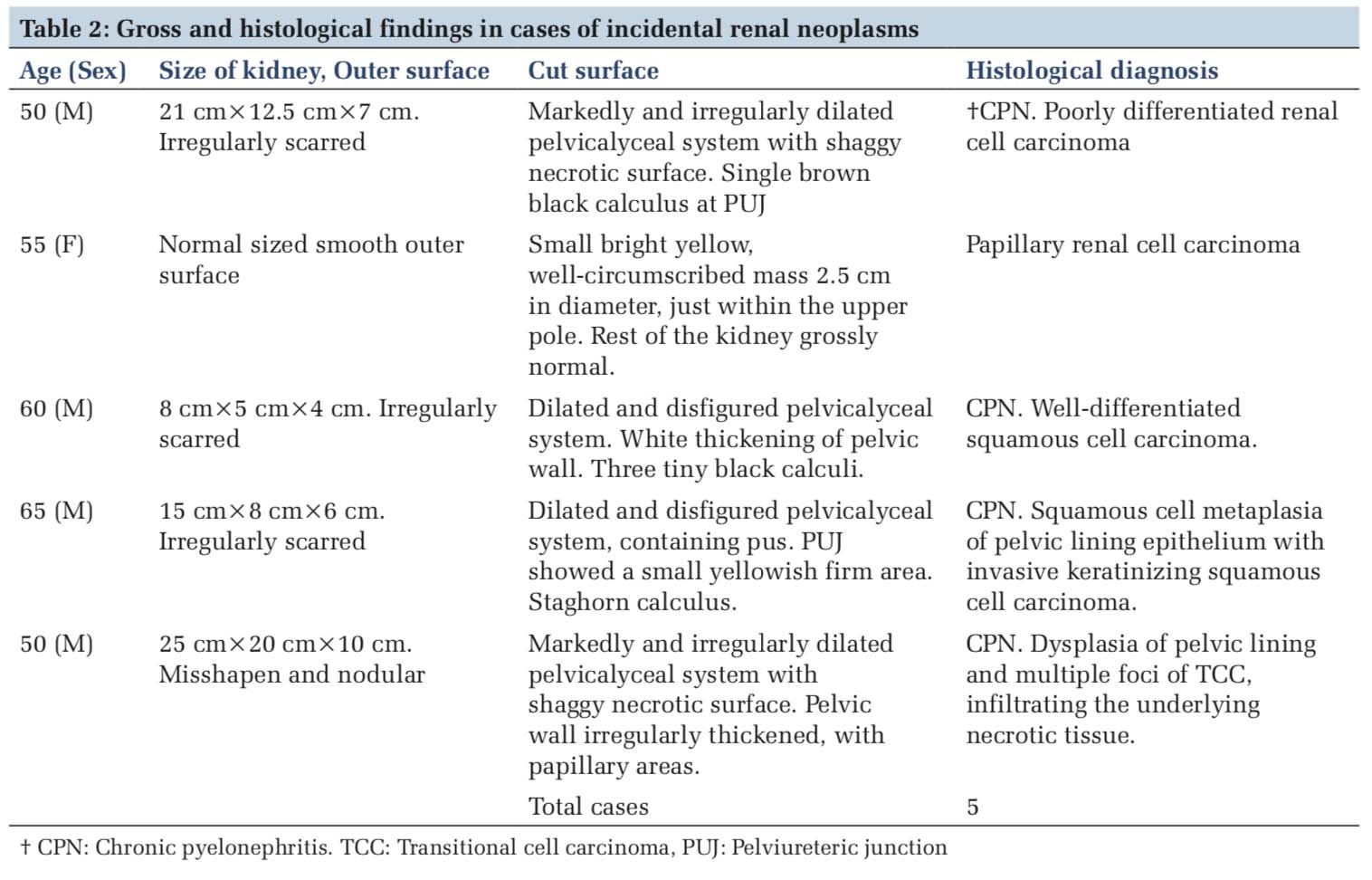

Detailed gross surgical pathology findings and histological diagnosis of the five cases under the study are tabulated in Table 2. It is evident that all but one, of our cases under study, were associated with hydronephrosis and complications. The neoplastic process was overshadowed by these processes and, hence, was clinically or radiologically unsuspected.

Case 1

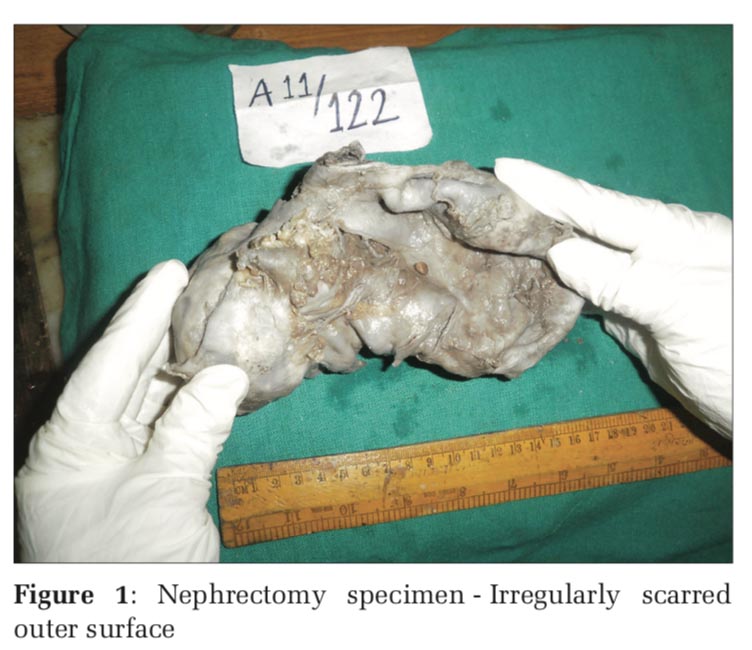

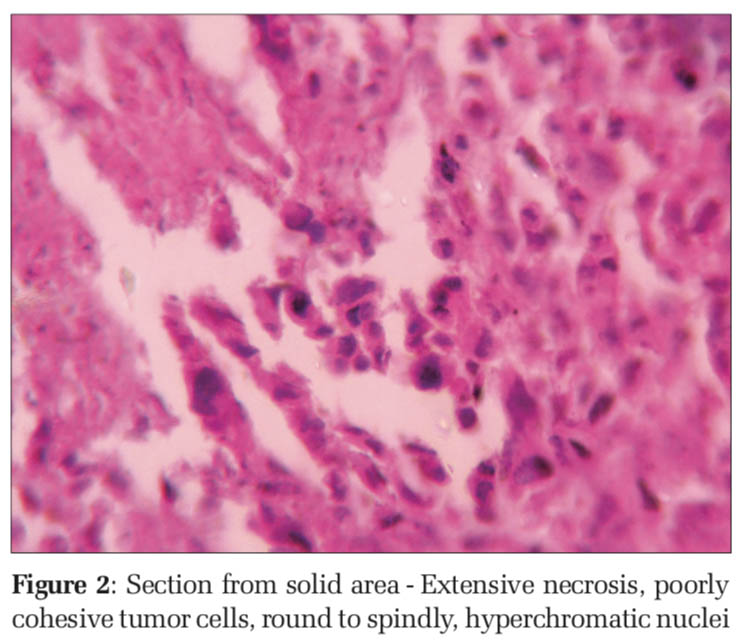

A 50-year-old male, a case of left-sided multiple renal calculi with massive hydronephrosis, underwent nephrectomy. Grossly, calculous pyonephrosis was seen, with a solid white hard area seen near the lower pole, toward the pelvic surface (Figure 1). Histopathological examination of sections from the hard white mass at the lower renal pole showed infiltration of renal parenchyma by sheets of pleomorphic round and spindle cells. Mitotic figures were numerous. Extensive areas of necrosis were present (Figure 2). The tumor was diagnosed as a poorly differentiated RCC. Immunophenotyping was advised for confirmation.

Case 2

A45-year-oldmalewasbroughtdeadtothehospital, following a road accident. A medicolegal autopsy Figure 1: Nephrectomy specimen-Irregularly scarred outer surface Figure 2: Section from solid area - Extensive necrosis, poorly cohesive tumor cells, round to spindly, hyperchromatic nuclei revealed a normal right kidney. The left kidney was normal on outer surface, but the cut section revealed a bright yellow, well-circumscribed tumor mass, 2.5 cm in diameter, just within the outer convex border, about midway between the poles. The case was a referral from a police station in a remote place, and the specimen was not well preserved. Hence, the gross picture could not be documented. Histological examination revealed a well-differentiated papillary RCC. Due to autolytic changes, a good microphotograph is not available.

Case 3

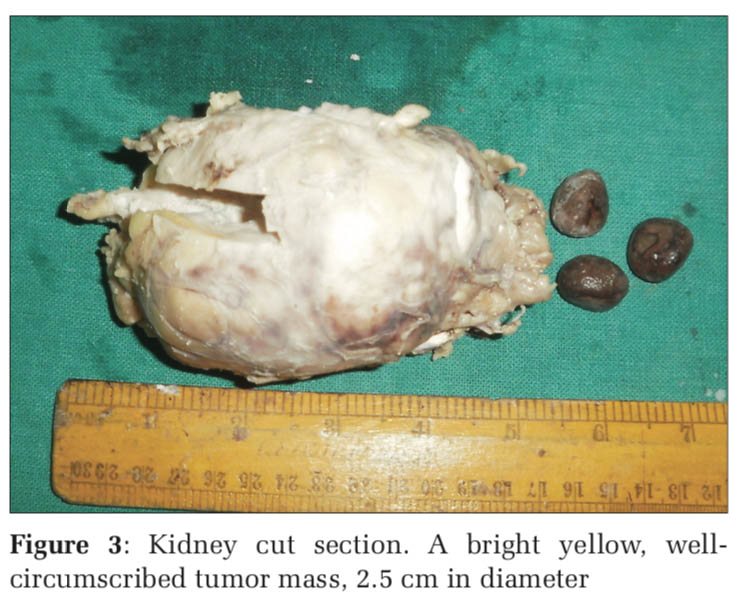

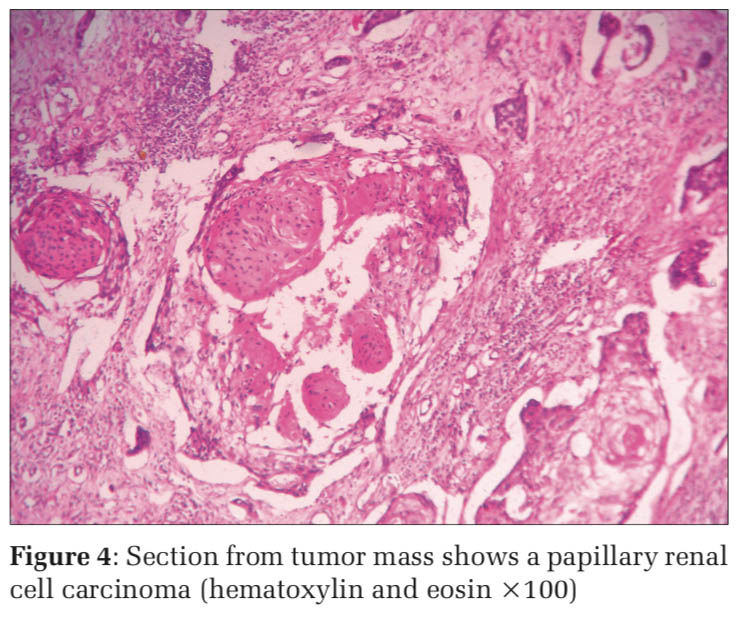

A 60-year-old male underwent a nephrectomy for non-functioning kidney due to renal calculi and hydronephrosis. Grossly, there were marked dilatation and distortion of the pelvicalyceal system associated with induration of the pelvic wall (Figure 3). Sections from the white-thickened pelvic wall showed histological features of well- differentiated keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (Figure 4). Sections from the rest of the kidney showed features of chronic pyelonephritis.

Case 4

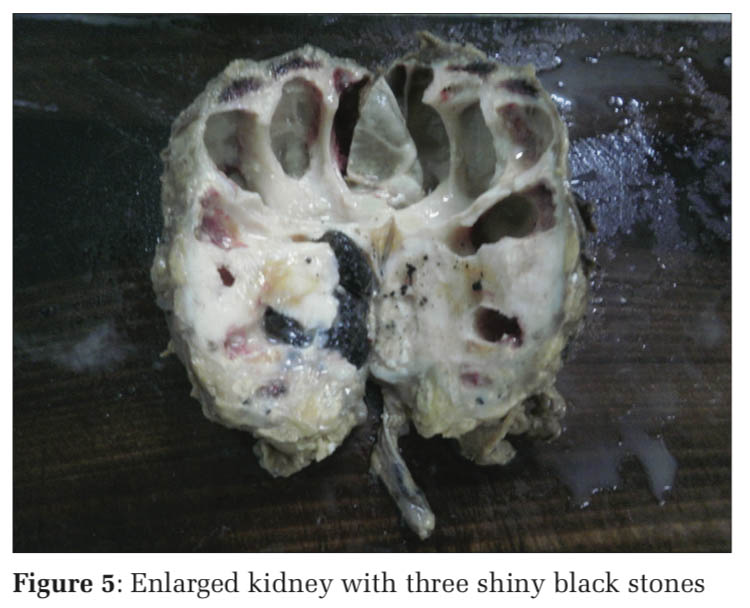

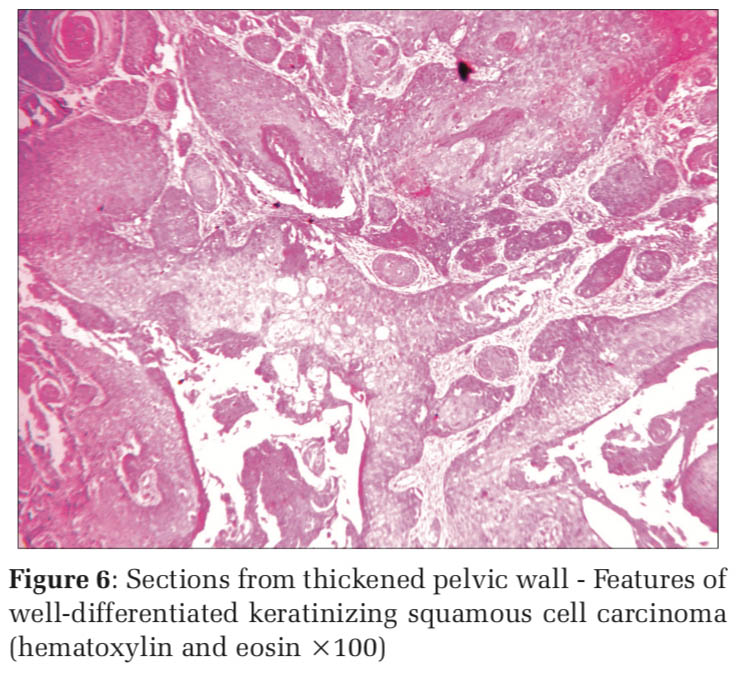

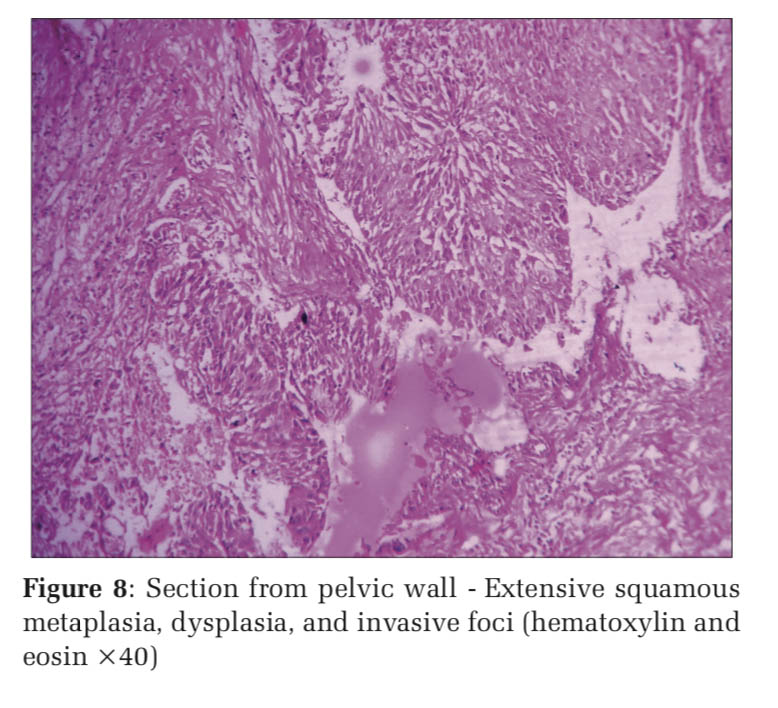

A 65-year-old male underwent a nephrectomy for a non-functioning left kidney due to staghorn calculus and pyelonephritis. Apart from the dilated and distorted pelvicalyceal system, a yellowish firm area was seen at the pelviureteric junction (PUJ) (Figure 5). Sections from most of the kidney revealed histological features of chronic pyelonephritis. There was extensive squamous metaplasia of the pelvic lining, with tongues of squamous epithelium infiltrating deeply (Figure 6). The small solid area at the PUJ revealed several foci of keratinizing SCC infiltrating into the surrounding necrotic material.

Case 5

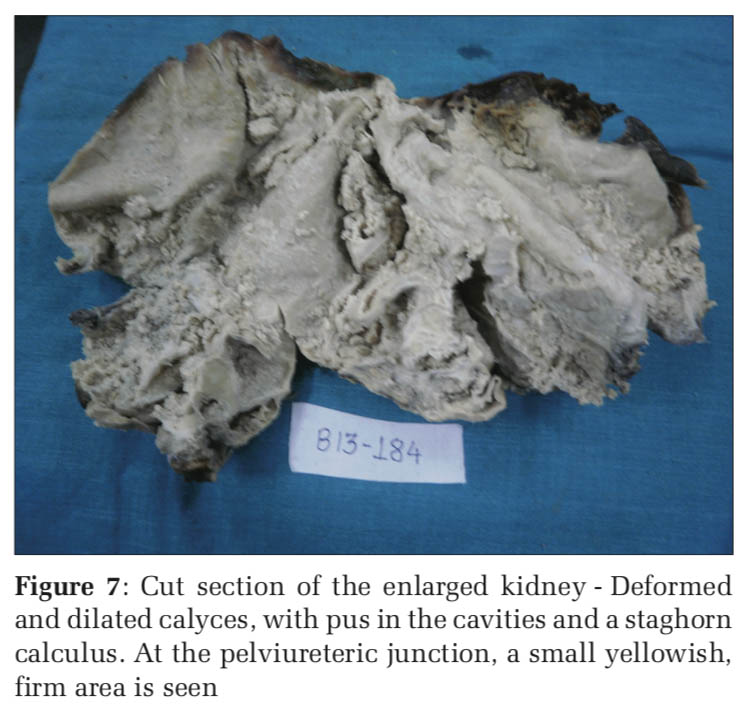

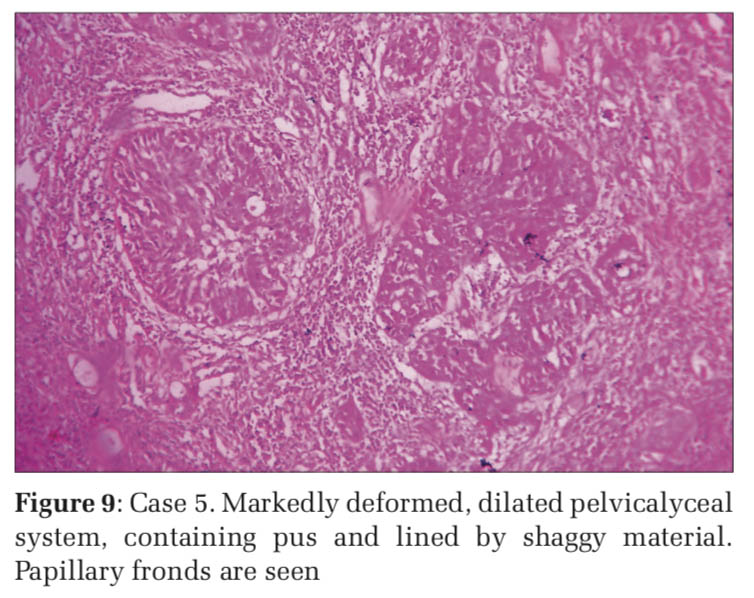

A 50-year-old male was operated for massive hydronephrosis. The kidney was markedly enlarged, with irregular dilatation of the calyces. There was shaggy necrotic lining to the calyces and the pelvis showed thickening of mucosa, with papillary fronds and an underlying solid yellowish area (Figure 7). Sections from rest of the kidney revealed features of chronic pyelonephritis. Sections from the thickened wall of the pelvis showed marked dysplasia of the urothelium (Figure 8) and the solid area in the pelvis showed multiple tumor foci of TCC in a necrotic stroma (Figure 9).

Hydronephrosis, with or without, calculi, was seen in 11 of our cases. Chronic pyelonephritis was present in all 14 cases. This is similar to most other studies.[1-6] The most common neoplasm was RCC in other studies.[1,2] In our series, we found an equal number of SCC and RCC, whereas SCC is a very rare tumor in other studies. However, the sample size is too small to establish any significant incidence.

We had one case from forensic material, an autopsy of a road accident victim. The diagnosis was papillary renal cell carcinoma. This was similar to the series of Kozłowska et al, where renal tumors were observed in 2.76% of unselected postmortem material.[7] The most frequent tumor types in this study were adenomas, clear cell carcinoma, and papillary carcinoma. In particular, the incidence of papillary carcinoma was found to be far greater than in surgical material. Of all urothelial tumors, only 5–6% occur in the upper urinarytract(renalpelvisandureter),andofthese, only about 6–15% are SCCs. Among malignant renal tumors, SCC is decidedly rare neoplasms and form only about 0.5% to 0.8%.[3-6] In general, these tumors are highly aggressive in nature and are usually present at an advanced stage when detected and have a poor prognosis when compared to the other upper urinary tract malignancies. Chronic irritation, inflammation, and infection induce squamous metaplasia of the renal collecting system, which may progress to dysplasia and carcinoma in some patients. Whether the calculus induced squamous metaplasia leads to the development of carcinoma or existence of SCC leads to the formation of calculus is not clear yet.

Radiologically, primary SCC of the renal pelvis may appear as a solid mass, with hydronephrosis and calcifications, or as a renal pelvic infiltrative lesion without evidence of a distinct mass. Patients may present with clinical features related to the renal calculi, hydronephrosis, and pyelonephritis, which usually accompany or precede the malignancy. A retrospective review of radiological findings in renal SCC showed that conventional radiological findings of filling defects, obstructive lesions, or non- functioning kidney by intravenous urography, which have been documented sporadically in the literature, are all non-specific.[9] Due to this, a renal tumor usually remains unsuspected. Further radiological evaluation such as computerized tomography (CT) is not done routinely in every case, especially in developing countries, where the cost of these investigations is an issue. Even if CT imaging is done, it does not help in exact diagnosis but may provide helpful information regarding the anatomical extent of the tumor. The non-specific clinical and radiologic features in renal SCC may cause diagnostic confusion and histopathology is needed for confirmation. In both of our cases, the diagnosis was not suspected preoperatively and there was no solid mass, only vague thickening of the pelvic wall. Both cases were associated with renal calculi. One case had a staghorn type calculus along with pyonephrosis, as seen in a series of Jain et al.[4] and Talwar et al.,[6] respectively. The case reported by Talwar et al. was associated with pyonephrosis, but unlike our case, there were no calculi. The occurrence of SCC of renal pelvis in the absence of calculi is rare.[6]

Lee et al.[9] classified renal SCC into two groups according to localization: Central and peripheral. Central renal SCC presents more with intraluminal components and is usually associated with lymph node metastasis, whereas peripheral renal SCC presents with prominent renal parenchymal thickening and might invade the perirenal fat tissue before lymph node or distant metastasis could be identified. Our cases were of the central type, involving the pelvic lumen and sparing the renal parenchyma. Elbarghati et al. reported a case with renal and pulmonary involvement.[10] Their case demonstrates the transition from calyceal urothelium to squamous metaplasia, dysplasia, and invasive squamous malignancy. These features helped to differentiate a renal primary from metastatic bronchogenic carcinoma. Similar metaplasia, dysplasia, and invasive SCC were seen in one of our cases.

Hence, our series underlines the fact that SCC may be missed, clinically as well as radiologically, in a number of cases, and the diagnosis may only be incidental during microscopic examination. This may require extensive sampling of the kidney, particularly of the renal pelvis, especially if there is any area of thickening. This is important because incidentally detected tumors have a significantly longer disease-free and overall survival than those with symptomatic tumors.[11]

SCC of the renal parenchyma is an extremely rare entity.[12] The diagnosis should be made after carefully excluding an urothelial component and pelvic origin, even in the absence of known risk factors for SCC. For it to be called a renal parenchymal SCC, the renal pelvis should be histologically normal.

Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) is much more common than SCC in the pelvic malignancies in a number of series.[5,13] We found two cases of SCC and only one TCC. This was probably because our sample size was very small and cannot be said to establish an incidence. Booth et al. found 200 TCCs and only three SCCs in their series.[13] Further, majority of primary urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis tend to be of a high histological grade and present at an advanced stage.[14] Perez-Montiel et al. found a number of unusual morphologic variants in their series - micropapillary, sarcomatoid, glandular differentiation, clear cell, and signet ring cell variant.[14]

All nephrectomy specimens, surgical or medico- legal, should be carefully grossed and thoroughly sampled so that we may not miss any incidental neoplasms. This is, especially, true in cases with calculi, where the overwhelming benign lesions of hydronephrosis and pyonephrosis may render the neoplasm difficult to detect. RCC, SCC, and TCC are the usual malignant neoplasms found in these specimens. The sample size is too small to document any morphological pattern.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.