Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2019.v05i03.006

Year: 2019, Volume: 5, Issue: 3, Pages: 35-38

Original Article

Rohit Balakrishnan1, Manju Aswath2

1Postgraduate student, Department of Psychiatry, Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India,

2Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bengaluru,Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Manju Aswath, Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. Phone: +91-9880476580. E-mail: [email protected]

Introduction: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a respiratory disorder characterized by airflow limitation that is usually progressive. Chronicity of this illness has been found to impair the day-to- day functioning in this population. These individuals are predisposed to psychiatric disorders which impact their morbidity. This study was planned as Indian literature in this area are sparse.

Aim: This study aims to study the psychiatric morbidity in individuals with COPD.

Methodology: Fifty inpatients in the Department of Pulmonology, Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bengaluru, diagnosed with COPD (Grade 3 and 4) consenting for the study were included in the study. Severity of COPD was staged using Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease criteria. Psychiatric disorders were diagnosed using ICD-10 criteria and Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. A descriptive study is used.

Results: Thirty- six of 50 patients assessed were found to have syndromal psychiatric disorders. Among them, 33 patients had tobacco dependence syndrome (TDS); 10 of whom had an additional psychiatric disorder (7 – alcohol dependence, 1 – moderate depression, 1 – generalized anxiety, and 1 – mixed anxiety-depression). The rest three had a single psychiatric diagnosis (1 – moderate depression, 1 – generalized anxiety, and 1 – dysthymia).

Discussion and Conclusion: This study showed increased psychiatric morbidity in patients suffering from COPD and two-third had TDS. Depression and anxiety were also seen associated with this illness. The presence of psychiatric disorders in COPD leads to increased morbidity. However, these have not been screened for routinely. Early detection and treatment of psychiatric comorbidity in COPD will help in reducing the morbidity and increase in the level of functioning.

KEY WORDS: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, psychiatric comorbidity, tobacco dependence syndrome.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common disease which is characterized by persistent progressive airflow limitation due to enhanced chronic inflammatory response of the airway to noxious stimulus. Common symptoms include dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum production. Its course is marked by periods of acute worsening of symptoms, called exacerbations.[1,2] Cigarette smoking is an important risk factor and a chief contributor to the mortality of COPD among adults.[3]

COPD is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The Global Burden of Disease study done in 2015 states that 3.2 million people across the globe died from COPD.It is estimated that in 2020, of 68 million deaths worldwide, 4.7 million would be due to COPD.[4-6] The prevalence of COPD among Indian males is 5% and females is 3.2%. It usually occurs in age groups of more than 65 years.[7,8] Chronicity of this illness has been found to impair the day-to-day functioning in this population predisposing them to psychiatric disorders, which, in turn, contributes to the morbidity in COPD. Common psychiatric comorbidities seen include substance use disorder, anxiety, and depression. Psychiatric comorbidities have a significant impact on mortality, exacerbation rates, length of hospital stay, quality of life, and functional status and hence influence the prognosis of patients with COPD.[9,10] This study was planned as Indian literature in this area are sparse.

The study was a cross-sectional, descriptive, quantitative study using purposeful sampling which involved 50 patients diagnosed with Grade 3 and Grade 4 COPD as classified by the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease. The study subjects were both inpatients and outpatients who were consulting the Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bengaluru. The subjects were included in the study after obtaining their consent and those subjects whose current health status prevented them from taking part in the study were excluded from the study. Necessary data from the study subjects were collected after their due assessment; the sociodemographic data were collected using a self-designed questionnaire for the study, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria were used for grading the severity of the COPD, psychiatric disorders were assessed using Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) questionnaire and ICD-10 criteria. The MINI was designed as a brief structured diagnostic interview for the major psychiatricdisordersinDSM-III-R,DSM-IV,DSM-5, and ICD-10. Validation and reliability studies done comparing the MINI to the SCID-P for DSM- III-R and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview showed that the MINI had similar reliability and validity properties when compared to both these instruments but can be administered in a much shorter period of time that is around 15 min. The standard MINI assesses the 17 most common disorders in mental health. Questions are phrased to allow only “yes” or “no” answers. Examples are provided to facilitate responses. The disorders investigated are the most important to identify in clinical and research settings and were selected based on current prevalence rates of 0.5% or higher in the general population in epidemiology studies.[11] The ICD-10 Chapter F is the tenth revision on definitions of mental and behavioral disorders published in 1992. The text has been extensively tested involving researchers and clinicians worldwide and is used in clinical applications, research, teaching and training, health statistics, and public health. The ICD forms the basis for diagnostic evaluation and further assessment and is used in my current study.[12]

The study was conducted after the submission and approval of the study protocol to the Ethical Review Committee of KIMS.

The study subjects were chiefly comprised men, accounting up to 66% of the study population. The mean age of the study population was 64.64. The majority of the study subjects were from a rural background and were from lower socioeconomic background. Of the 50 patients assessed, it was found that 33 patients were fulfilling the criteria for tobacco dependence syndrome (TDS). Seven had Alcohol Dependence syndrome, two had moderate depression, two had generalized anxiety disorder, one had dysthymia and one had mixed anxiety and depression.

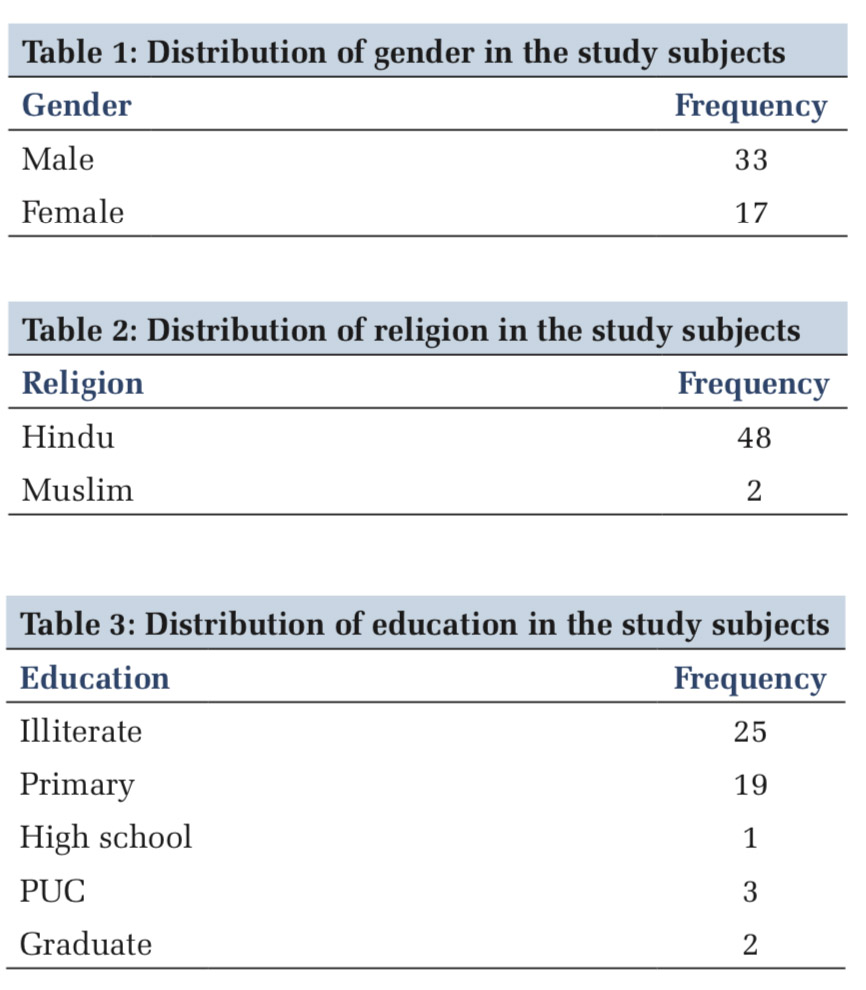

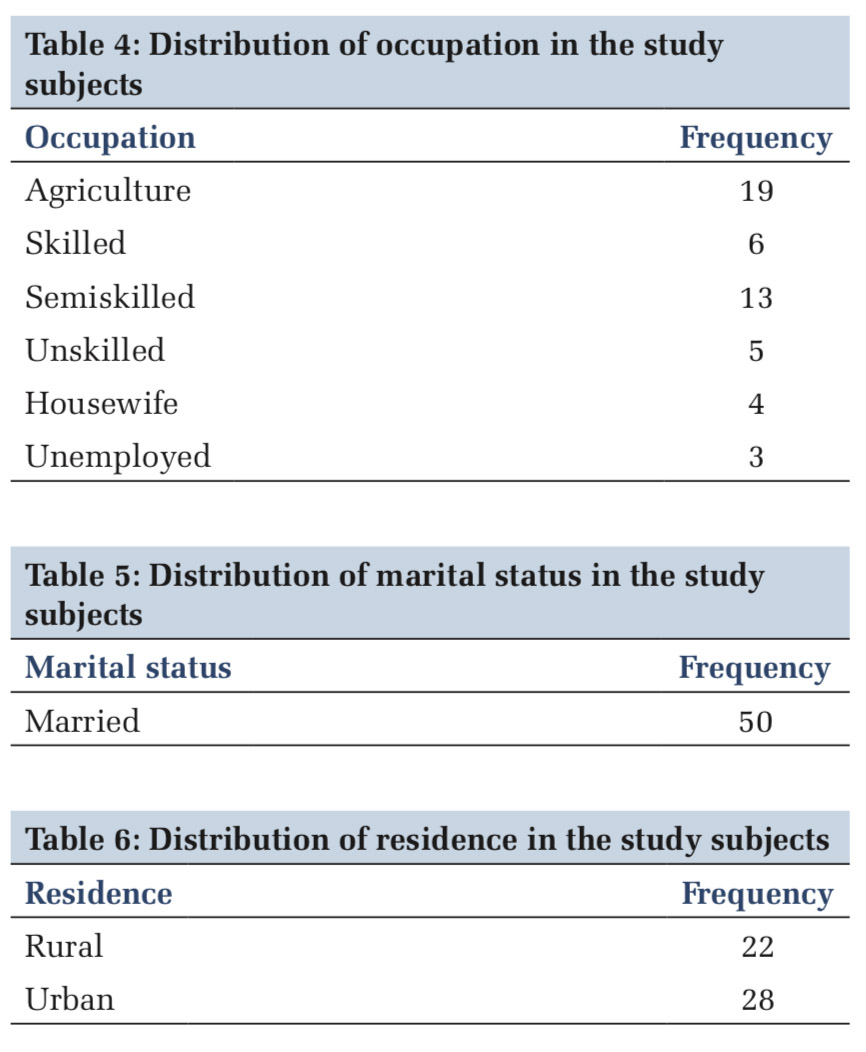

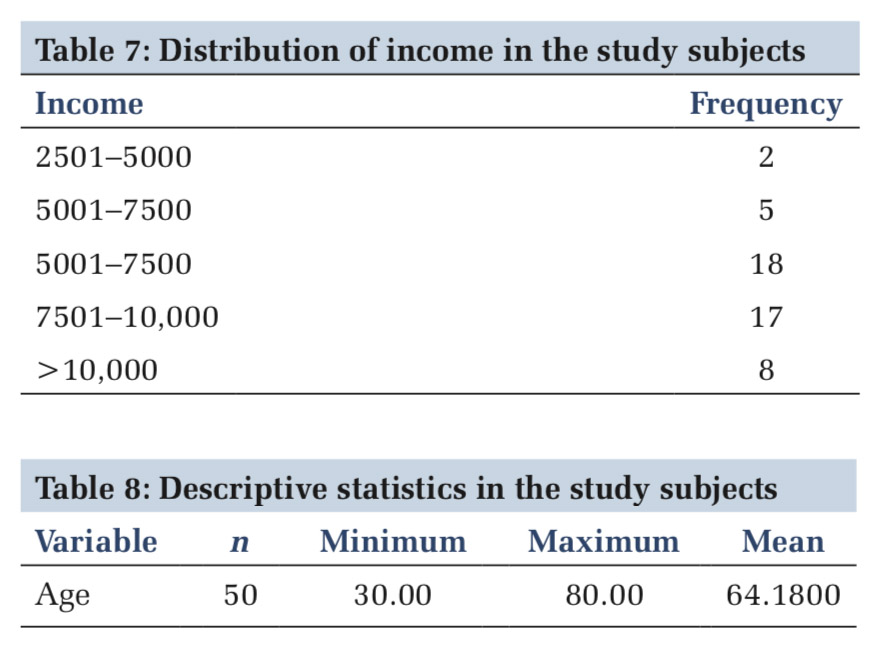

The current study was done to assess the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in individuals with COPD. The study subjects were chiefly comprised men, accounting up to 66% of the study population [Table 1]. The majority were Hindus(96%) [Table 2], illiterate(50%) [Table 3], had agricultural activity as a chief occupation (38%) [Table 4], married (100%) [Table 5], were from an urban background (56%) [Table 6] and had monthly income between Rs.5001 to Rs 7500 [Table 7]. The mean age of the study population was 64.1800 [Table 8]. Results showed increased psychiatric morbidity in patients suffering from COPD. It was found that of the 50 patients studied, 66% of patients were fulfilling the criteria for TDS. About 14% had alcohol dependence syndrome, 4% had moderate depression, 4% had generalized anxiety disorder, 2% had dysthymia, and 2% had mixed anxiety and depression. The most common psychiatric morbidity seen was TDS (57%) and the second most prominent was alcohol dependence syndrome. This is in concordance with a study done by Willgoss and Yohannes, in 2013, which assesses the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in chronic obstructive lung disease which showed that 10–55% of inpatients and 13–46% of outpatients suffering from COPD were suffering from anxiety disorder. The prevalence of specific anxiety disorders ranged considerably and included generalized anxiety disorder (6–33%), panic disorder (0–41%), specific phobia (10–27%), and social phobia (5–11%). The study emphasized on the need for further research on the effective management and screening for clinical anxiety disorder.[13] Similarly, an Indian study done by Chaudhary et al., in 2016, to assess the frequency of psychiatric comorbidities in COPD patients showed significantly higher psychiatric comorbidities in COPD patients (28.4%) as compared to controls (2.7%). Smoking is recognized as the most important causative factor for the development of COPD.[9] Lundbäck et al., 2003, addressing this issue reported that 50% of smokers eventually develop COPD, as defined by the GOLD guidelines.[14] This finding is of major clinical significance in that it provides a scientific basis for the advice that can now be given to smokers that if they continue smoking lifelong, they have at least a one in two chances of developing COPD. Alcohol dependence syndrome was found to be significantly associated with TDS followed by mood disorders. The presence of psychiatric comorbidities secondary to or associated with TDS in patients with COPD has been studied in few studies. A Finnish cohort study by Kupiainen et al. done to evaluate the role of smoking cessation on COPD comorbidities and mortality reported that alcohol abuse and psychiatric conditions were strongly related to lower success rates of smoking cessation which eventually lead to increased rate of mortality.[15] The above studies further emphasize the well-established hazard of substance dependence in relation to COPD and need of a multidisciplinary approach to manage the same.

The study shows the need for a multidisciplinary approach for early detection and treatment of psychiatric disorders in COPD. Tobacco is found to be one of the causative agents and a major risk factor for the development of the disease and can lead to worsening of severity of chronic obstructive lung disease on continued use. Hence, increase in awareness and early screening would help reduce morbidity and mortality in these patients and improve their day-to-day functioning.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.