Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2016.v02i03.001

Year: 2016, Volume: 2, Issue: 3, Pages: 1-5

Original Article

Monika Agrawal1 , Kapoor Ruchi2 , Bajaj Ashish3 , Saharia Pallab4

1Consultant, Department of Microbiology-Lab Medicine, Oncquest Laboratories Limited, New Delhi, India,

2Chief Consultant, Department of Pathology-Lab Medicine, Oncquest Laboratories Limited, New Delhi, India,

3Junior Consultant, Department of Microbiology-Lab Medicine, Oncquest Laboratories Limited, New Delhi, India, 4Consultant, Department of Pathology-Lab Medicine, Oncquest Laboratories Limited, Gurgaon, New Delhi, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Monika Agrawal, House No. 364, Sector 31, Gurgaon - 122 001, Haryana, India. Phone: +91-9717283380. E-mail: [email protected]

Context: Viral hepatitis is a serious health problem globally and in endemic countries like India. Viral hepatitis may present as mono-infection or co-infection caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, and hepatitis E virus (HEV). Co-infection with two or more viruses may lead to serious complications and increased mortality. To find out seroprevalence and co-infection of HAV and HEV infections in various age groups.

Materials and Methods: This study was done retrospectively on 475 samples for HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM) and HEV IgM antibodies from the patients with a history of viral hepatitis between January 2015 and December 2015. HAV IgM antibody testing was done by chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay, and HEV IgM antibodies were done by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results: Out of 475 samples, 181 samples were positive for HAV and/or HEV infection with an overall prevalence of 38.1%. Seroprevalence of HAV infection was found 9.4%, of HEV infection 23.3%, and of HEV-HAV co-infection 5.2%.

Conclusion: HAV and HEV infections are a major cause of viral hepatitis in India. Although both the infections are self-limiting, co-infection in rare cases may lead to acute hepatic failure and worsen the prognosis. HAV infections are more prevalent globally but HEV now found more prevalent in sporadic cases because of available vaccination for HAV, timely diagnosis and improved living standards.

KEY WORDS:Co-infection, hepatitis A virus, hepatitis E virus, viral hepatitis.

Viral hepatitis is a major public health problem in India and worldwide. Cases have been reported throughout the country.[1] Primarily, viral hepatitis is caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus, hepatitis D virus, hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis E virus (HEV) and dengue virus.[2,3]

Hepatitis A is caused by HAV that affects liver[4] and found worldwide. It is a non-enveloped 27-nmRNA virus in the genus Hepatovirus of the family Picornaviridae.[5]

On the other side, hepatitis E is caused by the HEV that is a non-enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded ribonucleic acid virus in the genus Hepevirus of the family Hepeviridae.[5] Globally, there are around 20 million hepatitis E infections/ year are being reported, over which 3 million cases are symptomatic. Around 56 600 deaths/year are related to hepatitis E.[6] In India during the period of 2011-13, 7.4% cases were positive for of hepatitis A and 10.4% cases were of hepatitis E.[7]

Mode of transmission of HAV and HEV is via feco-oral route, mainly thru contaminated water. Outbreaks and sporadic cases of hepatitis A and E occur globally but are closely associated with unsafe water, inadequate sanitation, and poor hygiene and health services in resource-limited countries. Hepatitis A and E are usually self-limiting diseases but can develop into fulminant hepatitis (acute liver failure).[2,4,6]

HAV mainly affects infants and young children in developing countries, whereas HEV primarily affects older children and young adults.[8,9] Clinically, hepatitis A and E infections may present as asymptomatic infection or mild hepatitis or sub- acute liver failure.[10,11]

In patient with preexisting chronic liver disease, both HAV and HEV infection can worsen the condition. The clinical course of HEV is more problematic than HAV infection, primarily in pregnant females’ contract disease in the second and third trimester. Therefore, HAV-HEV co-infection can lead to serious complications and increased mortality because of acute liver failure in patients in children as well as adults.[12,13]

Although clinical diagnosis of co-existence of HAV and HEV viruses as a cause of viral hepatitis is difficult and cannot be differentiated with mono- infection, laboratory diagnosis either by serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be a useful tool in the diagnosis of simultaneous presence of both the viruses.[11,14]

In our study, we have studied the seroprevalence and co-infection of HAV and HEV infections in various age groups. Study on seasonal variation of HAV/HEV infections was also included in the study.

A retrospective study was done from January 2015 to December 2015. A total of 475 serum samples of the patients with history of viral hepatitis, received from various centers to Oncquest Laboratories Ltd. in New Delhi, were tested for HAV and HEV immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies.

Samples with request of both HAV IgM and HEV IgM were included in this study.

Samples with request of either HAV IgM or HEV IgM were not included in this study. Tests requested for other viral markers such as hepatitis B surface antigen and HCV were also excluded.

HAV IgM was assessed on Architect 4100i (Abbott) by Chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay method, and HEV IgM testing was done using ORF 2 and ORF 3 synthetic peptide ELISA test kit (AMS S.p.A- Diagnostics Manufacturing, Italy).

All tests were carried out as per the manufacturer instructions.

The prevalence of hepatitis viruses was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.00001. The result was found statistically significant at P < 0.05.

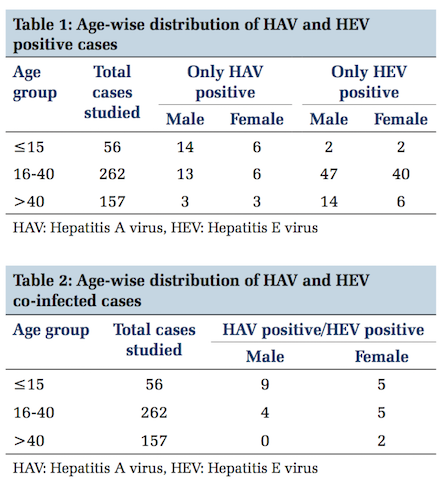

A total of total 475 serum samples were processed for HAV and HEV IgM. In age group of < 15 years, 56 cases; age group of 16-40, 262 cases and age group of >40 years 157 cases were studied. Among all the samples, 286 samples were of males and 189 samples were of females.

Out of 475 samples, 181 samples (38.1%) were positive for HAV and/or HEV. 45 samples were only HAV IgM positive, 111 samples were only HEV IgM positive and 25 samples were found positive for both HAV and HEV IgM. 294 samples were found negative.

The overall prevalence of HAV and HEV infection was found 38.1%. The prevalence of HAV infection was found 9.4%, HEV infection 23.3% and HAV- HEV co-infection was 5.2%.

Age-wise distribution of HAV and HEV IgM positive cases is depicted in Table 1.

Age-wise distribution of HAV and HEV co-infected cases is illustrated in Table 2.

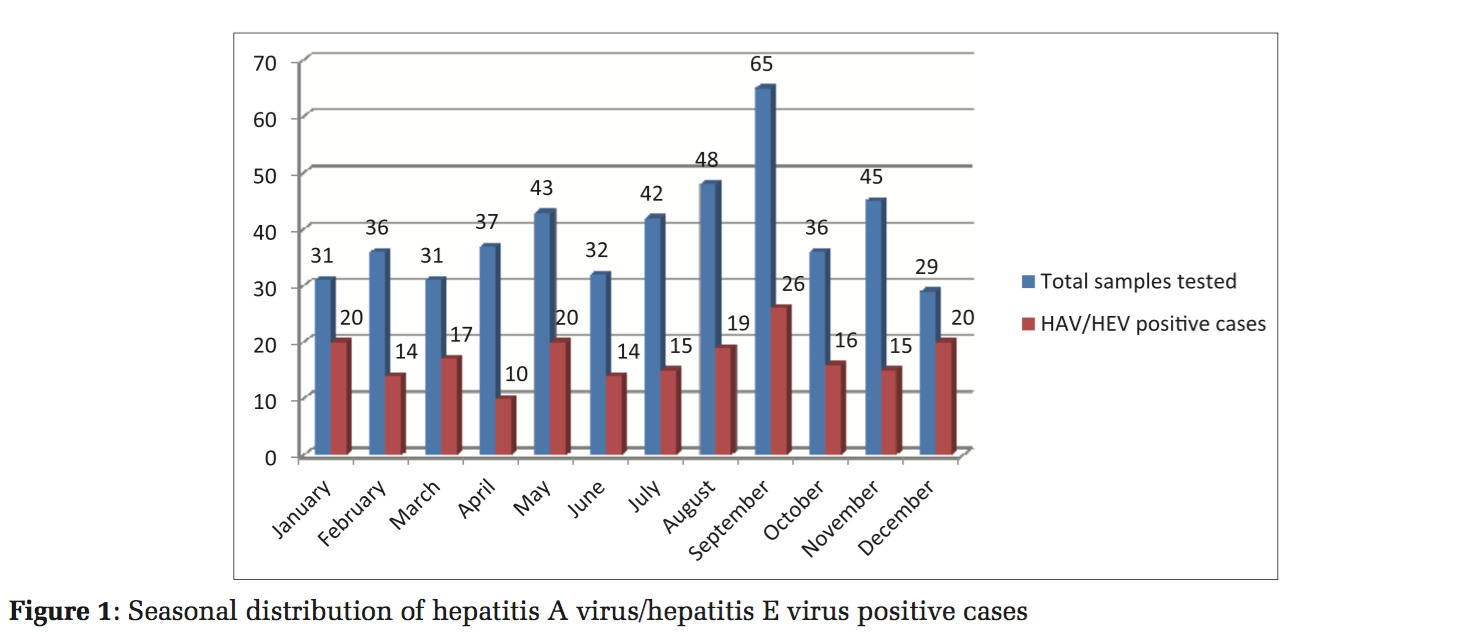

Seasonal distribution of HAV and HEV infections is shown in Figure 1.

Globally, HAV is found common cause of viral hepatitis[15,16] but in our study, HEV was identified with the prevalence of 23.3% as the major cause of viral hepatitis and more common than HAV (9.4%) which is in line of other studies from different regions of the country, ranging from 12.6% to 78.6%.[13,17,18] The reasons may be (1) High prevalence of anti-HAV antibodies in general population. (2) Availability of vaccine against HAV.[2,3] (3) Improved living standards and environmental hygiene.[19]

It is believed that HAV infection is a disease of infants and young children, but the same was not found in our study as children below < 15 years, older children and adult were found with the same seroprevalence; on the other side, we can say seroprevalence is decreasing in its respective age group. Community- based studies revealed that among schoolchildren, by the age of 5 years nearly 80% of children were found with anti-HAV antibodies and by the age of 16 years nearly all children had protective anti- HAV antibodies. This further strengthens the role of vaccination and improved living standard in decreased prevalence of HAV infection in various age groups and as a whole on seroprevalence.[20,21]

On the other side, HEV was found maximum positive (96) in population of 16-40 age group with slightly more frequent in males than females in comparison to 18 children in the age group of < 15 years. That justifies the preponderance of HEV infection in its respective age group that is in older children and young adults still remain the same.

Probability of lower HEV infection rates in children may be due to: (1) Anicteric HEV infections, therefore, children can go unnoticed.[22] (2) Subclinical HEV infections in the endemic area make children more immune and adult more vulnerable for HEV infection.[13,23]

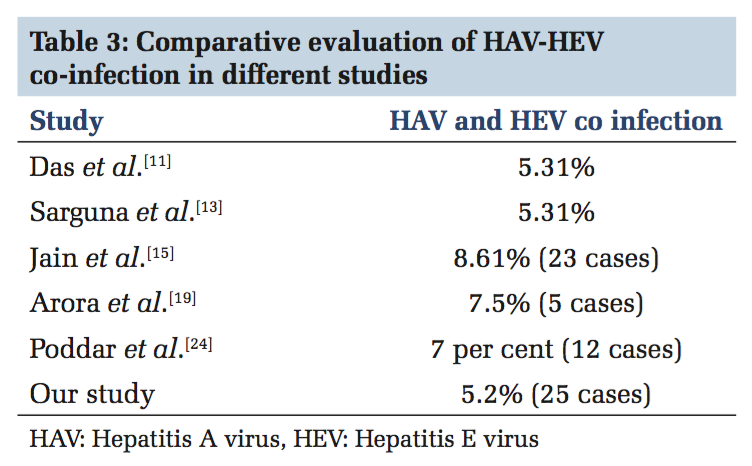

Co-infection with HAV and HEV was found in 25cases with the seroprevalence of 5.2% It is similar in various other studies also[11,13,15,19,24] shown in Table 3.

In our study, co-infection was found more common in age group ≤15 years. This is conjunction with other studies in which it was also predominantly present in children and was associated with 60% of acute hepatic failure.[12,25] Although in the presence of improved sanitary conditions, public education, vaccination for HAV infection and less prevalence of HEV infection in age group < 15 years, this finding was paradoxical. Reason could not be well understood, but possibility of co-existence of infection due to the same mode of transmission, doubtful immunity from both the viruses or with a divergent strain of virus could not be ruled out.[26]

Co-infection with HAV and HEV does not affect the prognosis of the patient much as these cases usually resolve with conservative treatment but in rare cases may lead to acute liver failure or hepatic encephalopathy.[12,13,22]

Although it is always a difficult to diagnose HAV- HEV co-infection clinically and by biochemical analysis, serology and PCR may help in timely diagnosis and identification of causative agent and support in prevention and management of acute liver failure in children and adult in India.

Seasonal variation of HAV and HEV was also studied as depicted in Figure 1.

Cases were reported throughout the year as these infections are endemic in India, with the peak of maximum number in September that is the rainy season. It is possible that cross contamination of drinking water with sewage could be more common during rainy season.[27] Cases are also reported in high number during the month of December, January, and May. We have collected the laboratory- based data; therefore, true seasonal variation in community could not be assessed.

Both HAV and HEV prevalence were detected higher in males than in females which had correlated well with another study. Outdoor and social activities of males may make them more vulnerable for the exposure than females.[28]

HAV and HEV infections are enterically transmitted and have similar risk factors, therefore the most effective method to control viral hepatitis is to prevent infection. That can be done by interrupting the route of transmission and focusing on proper sanitary condition, hygiene, and public education.[2]

Simultaneously vaccines can be used as a preventive strategy. Although HAV vaccine is in the market but not easily accessible and extremely high prevalence of anti-HAV antibody in the general population make it less cost effective for mass immunization in country like India, can be used in risk population like during onset of epidemics, chronic liver disease patients, travelers visiting endemic areas, etc. As HAV infection is common in younger children, inclusion of single dose inactivated HAV vaccine in immunization schedule of children can be useful.[2,3,11]

No specific treatment is available, complete rest following infection is important for recovery. Infection resolves without any sequel most of the time but in rare case of acute viral hepatitis or fulminant liver failure, liver transplantation is the end treatment.[3,13] As our study was done retrospectively, we could not find the final outcome of these infections in affected individuals.

In our study, HEV positivity was found in females of age group of 16-40 years, history of pregnancy was not available therefore exact impact of this disease on pregnant females could not be studied. As there are other causes of viral hepatitis other than HEV and HAV, therefore their correlation need to be required for better management and prevention.

Reduced incidence of HAV infection in its respective age group in sporadic cases is indicating the role of improved sanitary measures, public education, and vaccination. Although HEV incidences were found higher than HAV infection but did not show any shift and still follows the trend of preponderance in older children and adults. HAV and HEV co-infections are also not infrequent in endemic country like India as found in our study but are of a concern as it can lead to acute hepatic failure in children as well as adults and may worsen the prognosis in patient with chronic liver failure. With the help of clinical diagnosis and biochemical analysis only, one cannot rule out the possibility of dual infection, and timely diagnosis by serology and PCR may help in the early management and prevention from complications.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.