Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2021.v07i01.014

Year: 2021, Volume: 7, Issue: 1, Pages: 81-85

Original Article

Syed Shafiq1, Rajkumar P Wadhwa2

1Assistant Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, St. John’s Medical College Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India,

2Consultant and Chief, Department of Gastroenterology, Apollo BGS Hospitals, Mysuru, Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Syed Shafiq, Department of Gastroenterology, St. John’s Medical College Hospital, Sarjapur Road, Bengaluru - 560 034, Karnataka, India. Phone: +91-9986055875. E-mail: [email protected]

Background: Dyspepsia is undoubtedly one of the most common complaints that primary care physicians and gastroenterologists encounter in their clinical practice and encompasses a constellation of symptoms localized to the upper abdomen. While majority of these patients have “functional dyspepsia” with no endoscopic abnormality to account for their symptoms, benign conditions such as peptic ulcer disease and reflux esophagitis are the most common endoscopic lesions noted in “organic dyspepsia.”

Aim: The aim of the study was to study the clinical and endoscopic profile of patients presenting with uninvestigated dyspepsia (patients with new or recurrent dyspeptic symptoms in whom no investigations have previously been undertaken) at our center.

Materials and Methods:: A hospital-based retrospective observational study which included both inpatient and outpatient population over a period of 2 years, from December 2014 to November 2016. Patients’ charts from our hospital database were reviewed and data with regard to demographic variables, clinical and endoscopic profile of patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia was analyzed.

Results A total of 280 patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). The mean age of our study population was 45.2 years with 162 (58%) male and 118 (42%) female patients. The most common symptom was post-prandial fullness seen in 132 patients (47%). Endoscopy was reported as normal in 179 patients (64%) while 101 patients (36%) had an abnormal endoscopic finding with duodenal ulcer being the most common endoscopic abnormality (7.9%), followed by erosive gastritis (6.7%), reflux esophagitis (6.1%), gastric ulcer (3.9%), varioliform gastritis (3.2%), and esophageal/gastroesophageal junction malignancy (2.85%). Elderly (≥50 years) patients with alarm symptoms such as weight loss, dysphagia, and/or anemia had a higher incidence of malignancy.

Conclusion About two-thirds (64%) of our study population had functional or non-ulcer dyspepsia (normal endoscopic findings). The most common organic cause for dyspepsia was duodenal ulcer, followed by erosive gastritis, reflux esophagitis, and gastric ulcer. New-onset dyspepsia in elderly patients (≥50 years) with alarm symptoms such as weight loss, anemia, dysphagia, and/or jaundice warrants early endoscopic evaluation.

KEY WORDS: Alarm symptoms, duodenal ulcer, functional dyspepsia, reflux esophagitis, uninvestigated dyspepsia.

Dyspepsia, literally translates to “difficult or faulty digestion,” and includes a complex of recurrent or persistent symptoms localized to the upper abdomen such as abdominal bloating, belching, early satiety, postprandial fullness, epigastric pain/burning, nausea, and/or vomiting. The worldwide prevalence of dyspepsia is estimated to be about 7–34%,[1,2] while studies from the Indian subcontinent have estimated it to be around 30–49%.[3,4] Uninvestigated dyspepsia constitutes patients with new or recurrent dyspeptic symptoms in whom no previous endoscopic or radiologic investigations have been undertaken.[5]

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the single most important diagnostic test to distinguish organic from functional dyspepsia. A vast majority of patients with symptoms of dyspepsia have no identifiable endoscopic cause for their symptoms and are labeled as having functional dyspepsia or “non-ulcer dyspepsia.” The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying functional dyspepsia are thought to be delayed gastric emptying, hypersensitivity to gastric distension, altered motility of the gastroduodenal complex, dysregulated autonomic nervous system function, etc. Although studies have been inconclusive, infection due to Helicobacter pylori or other organisms has been implicated as a risk factor for dyspepsia particularly in areas of high prevalence with a meta-analysis by Moayyedi et al.,[6] showing a small albeit significant benefit in patients with functional dyspepsia from H. pylori treatment. The Rome IV diagnostic criteria for functional dyspepsia includes one or more of the following; bothersome postprandial fullness, bothersome early satiety, bothersome epigastric pain, bothersome epigastric burning, and no evidence of organic or structural cause (including at EGD) that offers a likely explanation for the patient’s symptoms.[7]

As elucidated above, the pathologic mechanisms underlying functional dyspepsia are unclear, while benign conditions such as peptic ulcer disease and reflux esophagitis account for a vast majority of organic dyspepsia, and a high index of suspicion should be exercised in patients with new-onset elderly dyspepsia (age ≥50 years) who present with “alarm symptoms” such as weight loss, dysphagia, odynophagia, and/or anemia, and endoscopic evaluation carried out expeditiously in such patients to rule out underlying malignancy.

There is a paucity of the literature with regard to patients presenting with uninvestigated dyspepsia; therefore, we aimed to study the clinical and endoscopic spectrum of such patients at our center.

This was a retrospective study carried out at Vikram Jyoth Hospital, Mysuru, over a period of 2 years extending from December 2014 to November 2016. A total of 280 patients (aged ≥18 years) presenting with dyspeptic symptoms lasting more than 3 months and not investigated previously, either endoscopically or radiologically, were included in the study, and their charts were retrieved from our hospital database. Patients below 18 years of age, terminally ill and uncooperative patients, a documented history of the upper gastrointestinal pathology or upper gastrointestinal surgery, clinical investigation of dyspepsia by endoscopy or radiology in the past were excluded from the study. All patients underwent EGD and biopsy for histopathologic examination where appropriate at the discretion of the endoscopist(s). Demographic data such as age, gender, history of smoking, and/ or alcohol, clinical symptoms, and endoscopic findings were recorded and analyzed using appropriate statistical methods.

Demographic characteristics

Our study included a total of 280 patients who underwent endoscopic evaluation for symptoms of dyspepsia lasting >12 weeks. The mean age of our study population was 45.2 years (range 18–82 years), of whom 162 (58%) were males and 118 (42%) were females.

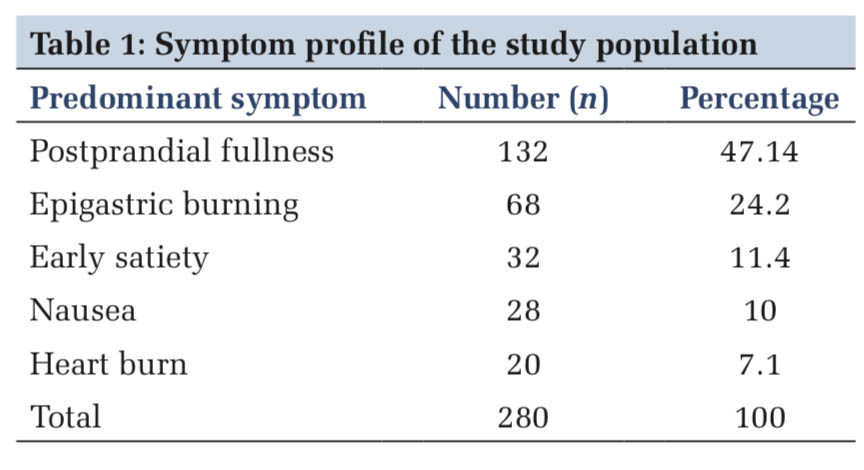

Symptom profile

Although a significant proportion of our patients presented with a combination of more than one symptomatology, the predominant symptoms were post-prandial fullness which was noted in 132 patients, followed by epigastric burning in 68, early satiety in 32, nausea in 28, and heart burn in 20 patients (Table 1).

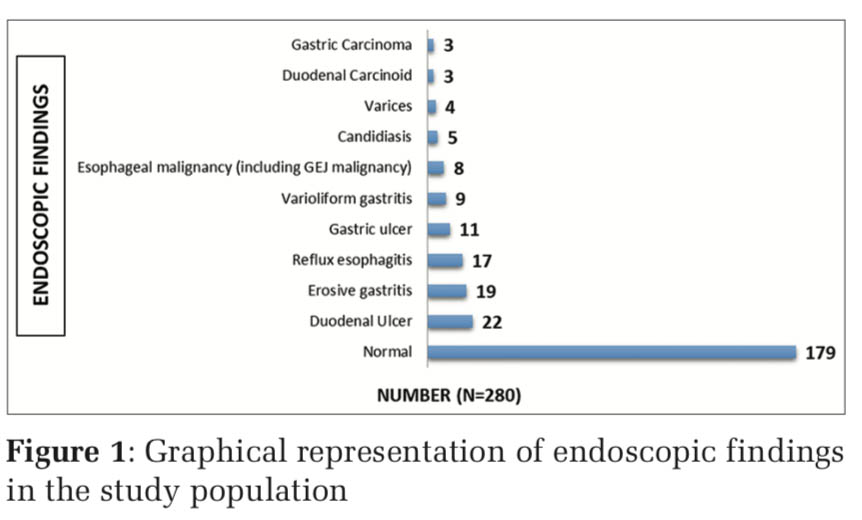

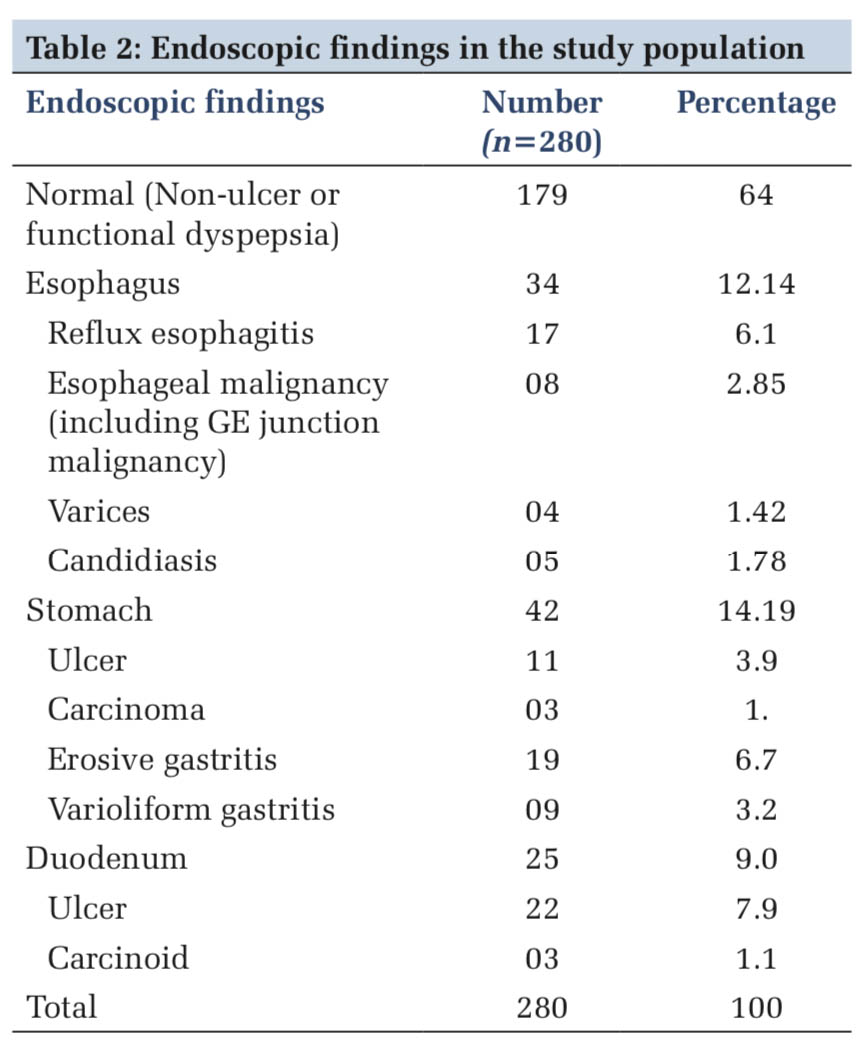

Endoscopic findings

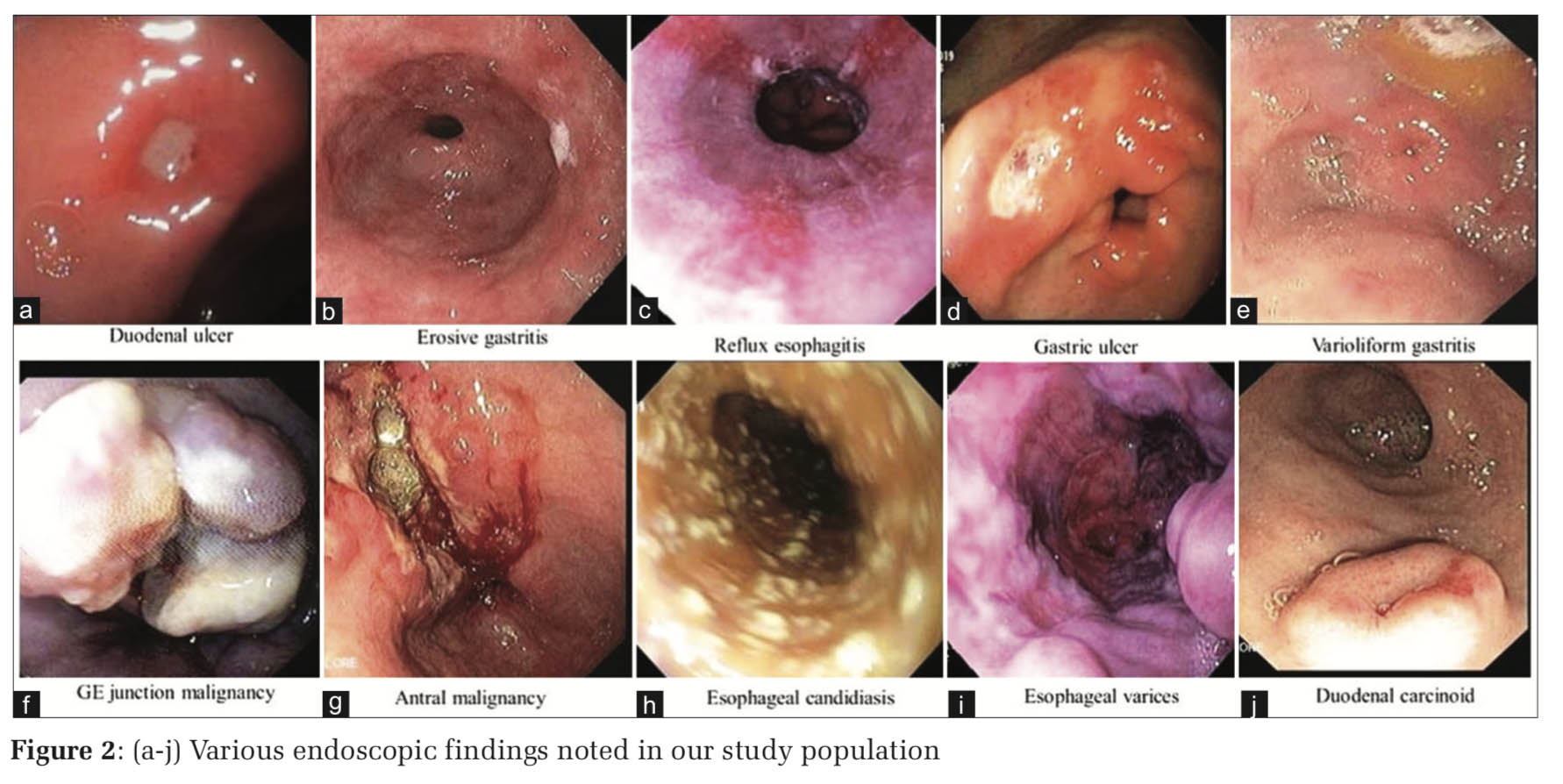

EGD failed to reveal any significant findings in 179 patients (64%) while a pathologic cause was found endoscopically in 101 patients (36%). Among those with abnormal endoscopic findings (36% of the patients), duodenal ulcer was the most common endoscopic abnormality seen in 22 patients (7.9%), followed by erosive gastritis in 19 (6.7%), reflux esophagitis in 17 (6.1%), and gastric ulcer in 11 patients (3.9%) (Table 2). Other less common endoscopic findings included varioliform gastritis, esophageal malignancies (including gastroesophageal junction malignancy), esophageal candidiasis, esophageal varices, gastric malignancy, and duodenal carcinoids (Figure 1).

Dyspepsia is a common complaint encountered in clinical practice and is estimated to affect about 30–49% of the Indian population[3,4] with a prevalence of 7–34% in the Western countries.[8-10] Functional dyspepsia, also referred to as non-ulcer dyspepsia, wherein the endoscopy is unrevealing, is the most common cause of dyspepsia worldwide.[11] Benign etiologies such as peptic ulcer disease and reflux esophagitis account for the vast majority of cases with organic dyspepsia. Patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia include those with dyspeptic symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks and in whom no previous investigation has been undertaken to elucidate the case of their symptoms.

Our study consisted of 280 patients presenting with persistent dyspepsia (lasting >12 weeks) and included 162 (58%) males and 118 (42%) females which is in concurrence with a similar study reported by Andrabi et al., from Kashmir, India.[12] A similar study by Gado et al., from Egypt showed a slight male (51%) preponderance over female (49%) patients.[13] This finding of male predominance in our study as well as others could be attributed to the social habits of smoking and alcohol which are commoner in men and which also play an important role in the pathogenesis of various gastrointestinal disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, and esophageal malignancy, thus accounting for the higher prevalence of dyspeptic symptoms in men. Our study showed that about two-thirds of the patients (64%) did not have any organic lesions on endoscopy to account for their symptoms and were classified as having functional dyspepsia. While Gado et al.[13] reported similar results with normal endoscopic findings in 65% of their patients presenting with dyspepsia, Andrabi et al., in their study,[12] have shown the prevalence of functional dyspepsia to be much higher at 73.1%.

The most common causes of organic dyspepsia (Figure 2) in those undergoing endoscopy in our study were duodenal ulcer (7.9%) and erosive gastritis (6.7%), followed by reflux esophagitis (5%) and gastric ulcer (3.9%). This is in accordance with previous studies by Talley et al. and Shaib and El-Serag, who reported gastroduodenal ulcers in approximately 10% of their patients who underwent endoscopic evaluation for dyspepsia.[14,15]

Esophageal and gastric malignancies (Figure2) were seen in 2.85% (n = 8) and 1.1% (n = 3) of our patients who underwent endoscopy, and of note, all these patients were aged above 50 years. A study by Sumathi et al., which included a total of 282 patients showed a higher prevalence of esophagogastric malignancies (8.27%) in their cohort.[16] In the study by Andrabi et al., about 3% of their subjects, all of whom were above 50 years, were noted to have esophageal and gastric malignancies on endoscopy.[12] A study by Kumar et al., reported the prevalence of gastric malignancies in 2.8% of their patients while Thomson et al. reported gastroesophageal malignancy in about 2% of their patients.[17,18] Therefore, endoscopic evaluation should be undertaken early in elderly dyspeptic patients (≥50 years) who present with recent onset dysphagia/odynophagia, weight loss, jaundice, and/ or anemia.

The main limitation of this study was its retrospective nature, and hence the results of this study are not representative of the general population.

Although the prevalence of dyspepsia is high in the general population, a vast majority of patients with “uninvestigated dyspepsia” have “non-ulcer or functional dyspepsia” as evidenced by normal endoscopic findings. Gastroduodenal ulcers and reflux esophagitis are the most common endoscopic findings in patients with “organic dyspepsia.” Patients aged ≥50 years who present with new-onset dyspepsia and those with worrisome symptoms such as dysphagia or odynophagia, early satiety, weight loss, anemia, and recurrent symptoms despite acid suppression therapy constitute a high-risk group and require urgent endoscopic evaluation.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.