Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2020.v06i03.003

Year: 2020, Volume: 6, Issue: 3, Pages: 14-18

Original Article

K Suhruth Reddy1, M Kishor2, VG Manjunath3

1Resident, 2Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, JSS Medical College, JSSAHER, Mysuru, Karnataka, India, 3Professor, Department of Paediatrics, JSS Medical College, JSSAHER, Mysuru Karnataka, India

Address for correspondence:

M Kishor, Department of Psychiatry, JSSMC, JSSAHER, Mysuru, Karnataka, India. Phone: +91-96986712210. E-mail: [email protected]

The World Health Organization considers poisoning among the leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Poisoning in India is among the highest in the world. Childhood poisoning ranges 0.33–7.6%. Most commonly observed among the children in the age group of 1–5 years. The mortality rate due to poisoning is 3–5%. Accidental exposure is considered the most common reason for poisoning. However, there is a scarcity of studies in India which explores the nature of poisoning in children. A retrospective register- based study was carried out in a tertiary care urban hospital. Information about children who were admitted in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of tertiary care hospital, between the time periods of December 2016 and December 2018 with a history of poison consumption was included in the study. Seventy-six children were admitted for poisoning; the majorities were of the male gender. Almost half of them were < 2 years. The common compound implicated in poisoning was thinner, a solvent used for paints. Majority were recorded as accidental exposure. Some were suspected to be of intentional nature. Poisoning in Indian children is an area of concern. Most of the studies among children are on accidental poisoning. Intentional poisoning is not reported. This study highlight, the need for comprehensive assessment involving pediatricians, psychiatrists, and forensic medicine experts for prevention and management of childhood poisoning and the need for more research, especially in relation to intentional poisoning.

KEY WORDS:Children, accidental poisoning, intentional poisoning, filicide.

As per the World Health Organization estimates, around 0.3 million people die due to poisoning. The incidence of poisoning in India is among the highest in the world. Intentional poisoning is also an important cause of morbidity worldwide. Although analgesics, tranquilizers and antidepressants are the common causes in industrial countries, agricultural pesticides are usually the culprits, especially in Asian countries like India. Easy availability of pesticides and lack of proper storages is one of the causes for their increased use.[1] The incidence of childhood poisoning in various studies ranges from 0.33% to 7.6%. Poisoning is most commonly observed in children at 1–5 years of age and constitutes 80% of all poisoning cases. The mortality rate due to poisoning is 3–5%.

Poisoning is one of the most common medical emergencies in childhood across the world. Around one-fourth of the accidental deaths among the age group 1–15 years are due to poisoning.[2] Poisoning most commonly occurs between the ages of 1 and 5 years. During the 1st year of life, medications given by the parents are the common cause of poisoning. Among the causes of poisoning, house cleaning products are common between the ages 2 and 3 years and medicines left unattended between the ages 3 and 5 years.[3]

Profile and outcome of poisoned pediatric patients are influenced by the prevalent social, economic and cultural practices and availability and the quality of the medical facilities. With increasing urbanization and rapid socioeconomic development in India during the last decade, change in pediatric poisoning profile and outcome is to be expected.[2]

Apart from accidental poisoning, intentional poisoning is also another area of concern in children. A study done by Spiller et al. concluded that incidence and rates of suicide attempts in children < 19-year-old have increased significantly after 2011.[4] There is also the use of over the counter drugs for intentional poisoning. There has been a recent increase in the number of cases of intentional poisoning, due to the use of paracetamol.[5]

Intentional poisoning in children is a major concern, particularly if the child has been poisoned by others. It is even more distressing when the mother is the perpetrator due to the expectations that mothers are selfless and tend to protect their children at all cost. Filicide of an unwanted child is the most common reason for taking the life of a newborn.[6] Ninety percent of the homicides involving a child, perpetrators were biological parents. Among the causes of the filicide, around 30% of mothers who kill their children end up committing suicide.[7] Psychiatric illness in the parents, especially in acute psychotic states, delirious states, or postictal confusion states can also result in death or harm to a child.[8,9] Most often, the weapon used was dependent on the age of the child, and perpetrator used his or her hands and feet if the child was an infant or young. Lethal weapons were used for older children.[10]

As there is a scarcity of data from India for better understanding the factors responsible for poisoning in children, there is a need for further exploration to formulate early interventions and better treatment strategies to address poisoning in the children, including intentional poisoning.

Retrospective register-based study of patients aged below 18 years who were admitted for poisoning in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) at tertiary care hospital, from December 2016 to December 2018, was carried out after obtaining the Institutional Ethical Committee clearance. Information was collected from the PICU registers, which contained details such as sociodemographic details, such as date of admission, type of poisoning, age, and gender of the child. Electronic records such as case file containing detailed description on the nature of poisoning were also taken from hospital database.

A descriptive study was carried out. Sociodemographic data, such as age and gender, were analyzed. Nature of consumption was analyzed. It included whether the patient had consumed the compound intentionally, or whether there was an accidental consumption or whether it was of filicidal nature. Type of the compound consumed was assessed.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics was used to study the frequency and percentage using SPSS 23 [Statistical Package for the Social Sciences].

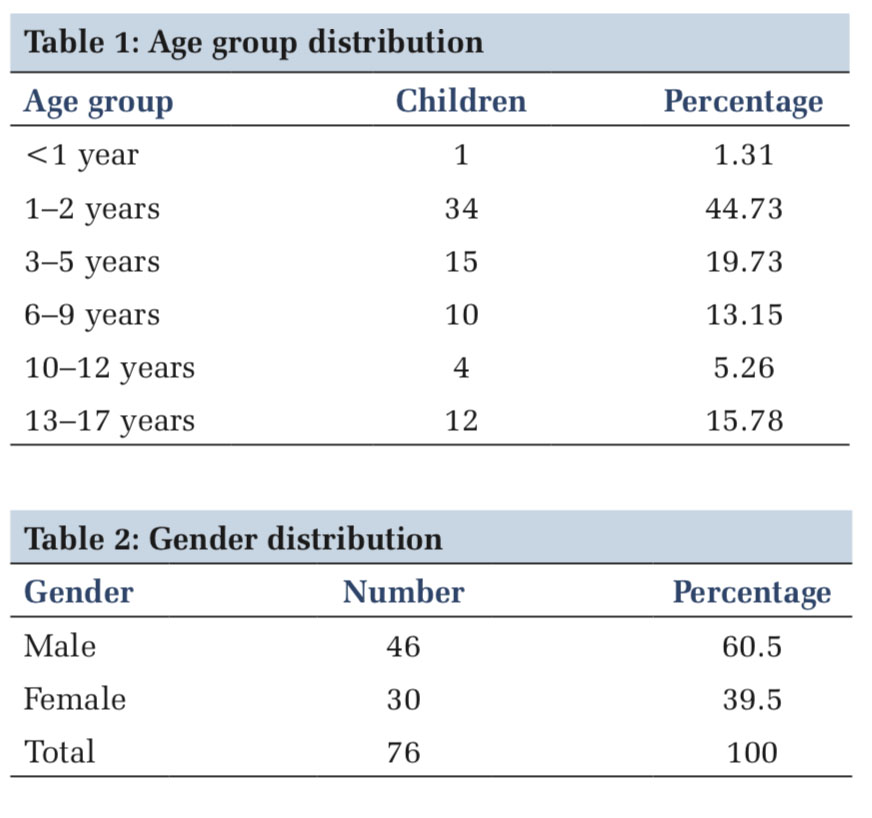

Seventy-six children were admitted for poisoning. Age of the children ranged from < 1 year to 17 years, 1 child below 1 year of age was admitted for poisoning; similarly, 34 children between the ages 1 and 2 years, 15 children between the ages of 3 and 5 years, ten children between the ages 6 and 9 years, four children between the ages 10 and 12 years, and 12 children between the ages 13 and 17 were admitted in PICU for poisoning.

The majority (44.7%) of children were within the age group of 1–2 years which constituted the group with the highest representation and 1.3% of children were within the age group of less than 1 year which constituted the group with the lowest representation [Table 1 and Figure 1].

Out of the 76 children, 60.5% were male and 39.5% were female [Table 2].

Forty-eight (63%) out of 76 children were from rural background. Only 37% of children were from urban background [Table 3].

Seven of the 76 cases (9%) of the cases resulted in deaths, of which 57.1% were female and 42.9% were male [Table 4].

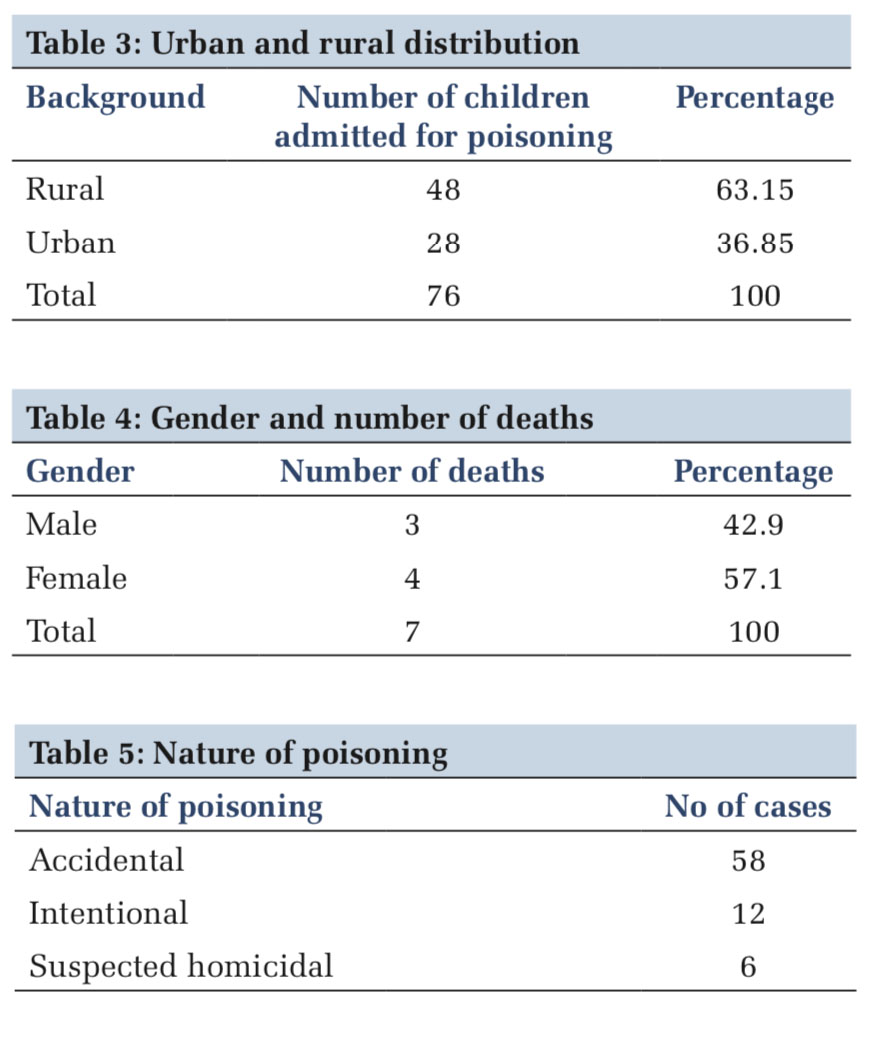

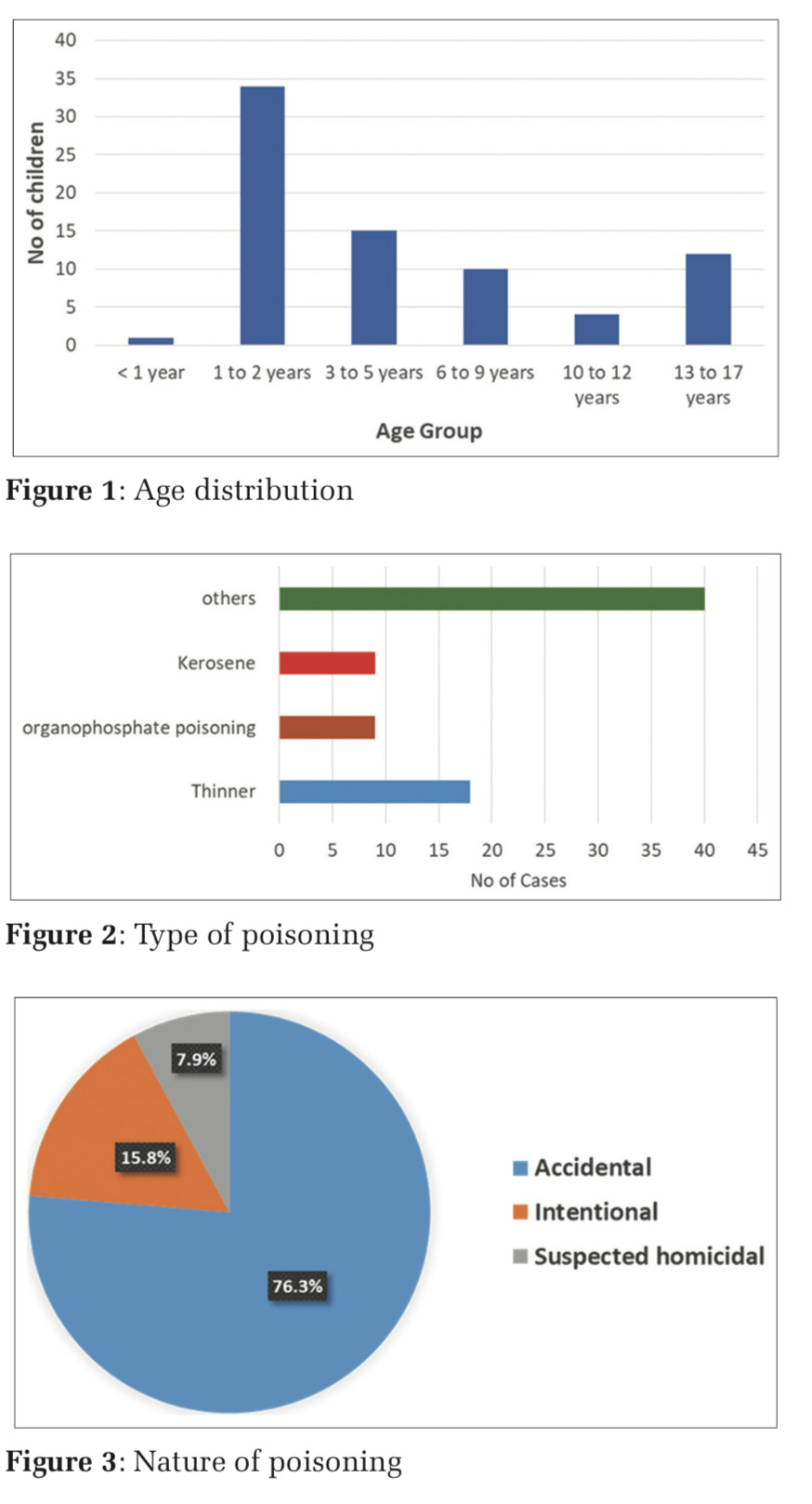

Most common compound implicated was thinner (mineral spirits such as toluene and acetone) poisoning in 18 cases. Other used compounds were organophosphate poisoning in nine cases and kerosene poisoning in eight cases [Figure 2]. Out of the 76 poisoning cases, 58 were accidental, 12 were intentional, and six were suspected to be homicidal in nature [Table 5 and Figure 3].

Findings from two of the discharge summaries showed alleged poison being mixed in the food item and were then fed to the children. However, no further details could be elicited from remaining four discharge summaries. There were accounts from the treating doctors regarding the nature of the poisoning, but no records could be found.

Poisoning among children is a major concern. In the 2-year timeline between December 2016 to December 2018, a total of 2016 patients were admitted in the pediatric ICU, out of which 76 were admitted for poisoning.

Out of 76 children, 50 children (65.7%) were below the age of 5 years. Similar distribution was also seen in a study conducted by Das Adhikari et al., where 77.42% of children were below the age of 5 years, which seem to be in line with the study done by Reddy et al., where 70.4% were within the age group of < 5 years.[2] The study conducted by Agarwal et al. also reiterated this point with the majority of children belonging to 1–3year age group.[3] Hence, children younger than 5 years in India are vulnerable age for poisoning.

Most of them (60.5%) were male gender and which correlate with other studies. In a study conducted by das Adhikari et al., 62.79% were male.[2] Similar results were obtained in a study conducted by Reddy et al., where 53.1% were male.[11] However, the study conducted by Sahin et al. reported that the majority were female (51.6%).[12] It is difficult to interpret which gender is vulnerable in the Indian context with changing socioeconomic scenario, the gender gap in poisoning may not be significant.

Majority of children were from a rural background in our study. This is in accordance with another study, where the rural representation was 65.54%.[3] However, a study conducted by Pac-Kożuchowska et al. states that the majority of poisoning was in urban settings, whereas the majority of accidental poisoning was in rural settings.[13] The distribution can be explained by the fact that the majority of patients visiting the tertiary care hospital are from rural background. A comparative study between rural and urban India in the future can help in enhancing our understanding of poisoning pattern among children.

Eighty percent of the cases were of accidental nature in our study which matches with the studies done by Reddy et al. and Sahin et al.[11,12] Twenty percent cases were not of accidental nature. They were either intentional or homicidal in nature. Psychiatrists were consulted in only 12 cases where there was proven intentionality, but not in case of poisonings that were suspected to be homicidal in nature. In many cases accidental poisoning especially in children less than 10 years were not referred to psychiatrists, where there might be a chance of them being homicidal by nature. It is important to recognize that apart from legal experts, mental health specialist can look into the mental health issues in the family so that management and prevention strategies can be carried out together. It is possible that in many suspected cases, family members may have refused consultation from psychiatrist due to stigma or might not have reported the homicidal nature due to legal implications. Hospital social workers or psychiatric social workers can be involved in such issues. It is possible in some cases that homicidal attempts are part of suicidal pacts, these can be explored if the multidisciplinary team involving pediatrician, psychiatrist, and forensic medicine looks into all cases of childhood poisoning.

Limitations

It is a retrospective register-based study. The information was collected from a register handled by various physicians which would have affected the uniformity in data collection and the possibility of attenders concealing information could not be addressed. The study was restricted to a tertiary care center, so it cannot be generalized to the entire population. No interventions were planned for the children and the family and the mental health issues were not explored. Although the study makes an effort to improve our understanding of the nature of poisoning in children, more systematic studies with large sample size will shed some more light in this aspect.

Future directions

All child poisoning cases should be comprehensively assessed involving pediatricians, psychiatrists, and forensic medicine experts so that prevention and management are offered for complete care.

Poisoning in children is an area of concern. Majority of studies are on accidental poisoning. Intentional and homicidal nature of poisoning is usually overlooked. Addressing this issue is paramount for prevention and comprehensive management of poisoning in children.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.