Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2019.v05i02.006

Year: 2019, Volume: 5, Issue: 2, Pages: 28-32

Original Article

Pallavi Gedam1, Sanjay M Chawhan2

1Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, Government Medical College, Gondia, Maharashtra, India,

2Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, Government Medical College, Gondia, Maharashtra, India

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Sanjay M Chawhan, Department of Pathology, Government Medical College, Gondia, Maharashtra, India.

Phone: +91-9823642628. E-mail: [email protected]

Introduction: Prostate disease is an important growing health problem, presenting a challenge to urologists, radiologists, and pathologists.

Objectives: The aim of the study is to correlate prostatic-specific antigen test with histopathological examination in prostatic lesions and to recommend combine approach for management of the patients of prostatic lesions.

Materials and Methods:This was a prospective study conducted at the department of pathology in a tertiary care center over 6 months. Data were collected from histopathology record department. The 2002 WHO classification was used to diagnose and classify prostate tumors. Gleason’s grading system was used for the cases of adenocarcinoma.

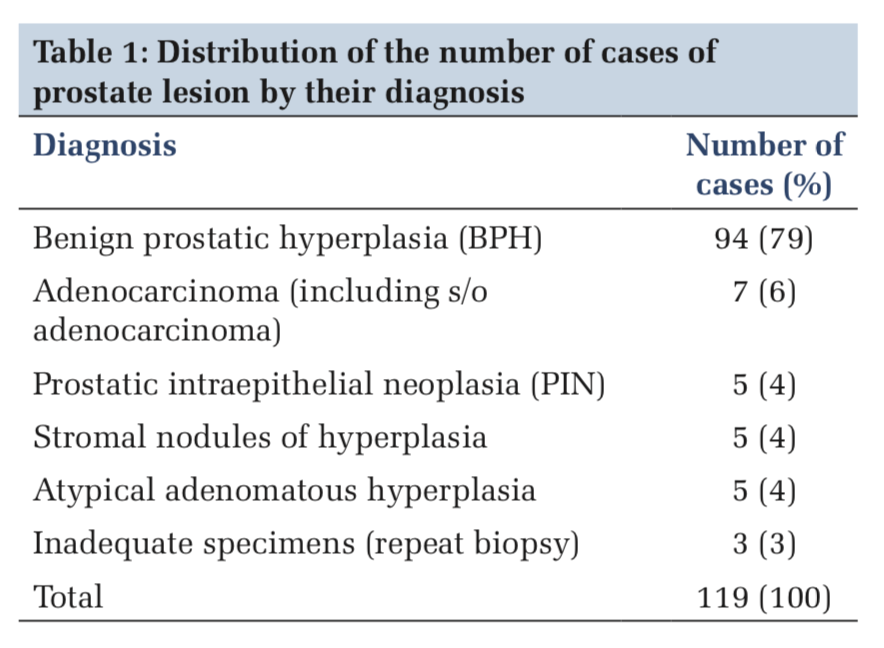

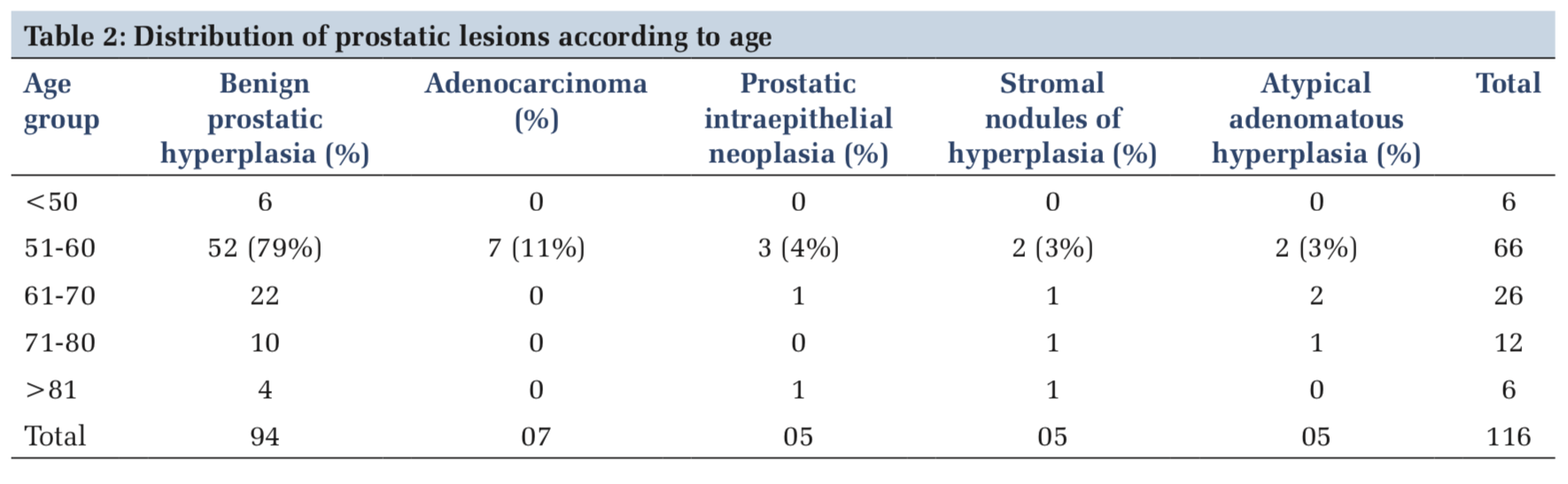

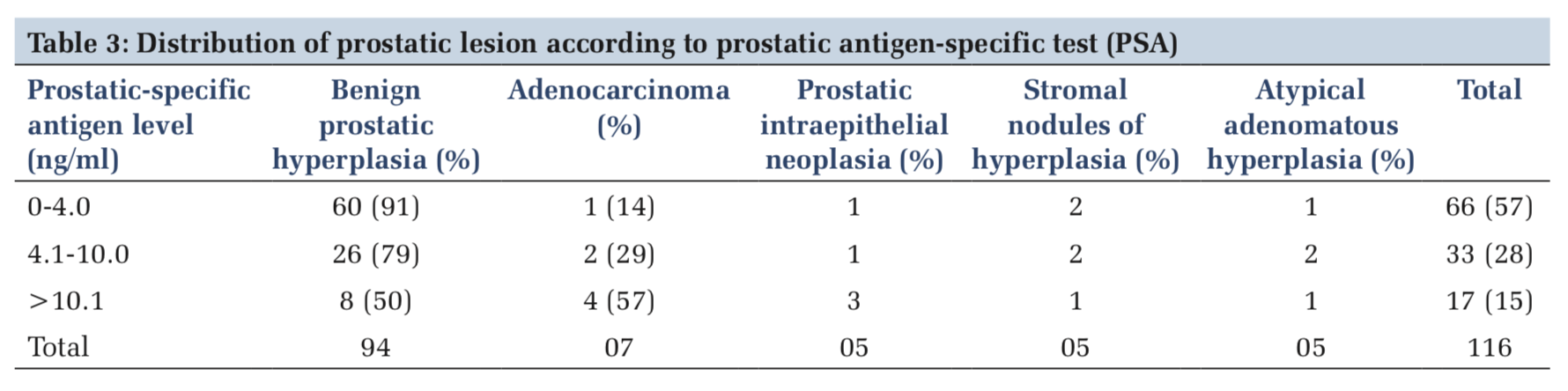

Results: In our study, a total of 119 cases of prostatic lesions were noticed. The lesions diagnosed were benign prostatic hyperplasia (79% of cases), adenocarcinoma (6% of cases), prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (4% of cases), stromal nodules of hyperplasia (4% of cases), and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (4% of cases). A total of 3% of cases were inadequate. Majority of prostatic lesions were belonging to the 6th decade followed by the 7th decade. All cases of adenocarcinoma were belonging to the 6th decade. The test of prostatic-specific antigen was higher (more than 10 ng) in cases of adenocarcinoma.

Conclusions: The study is conducted to see that combine approach of prostate-specific antigen and histopathological examination is useful for its recommendation, for better management of prostatic lesions in tertiary care center.

KEY WORDS:Benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, prostate-specific antigen test, prostate-specific antigen.

Inflammation, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and tumors are important prostatic diseases that cause mortality and morbidity in males. The second most commonly diagnosed cancer is prostatic carcinoma globally and the sixth leading cause of death due to cancer in males.[1] In India, it contributes around 5% of all male cancers.[2] The most commonly used tools to screen for prostate cancer are prostate- specific antigen (PSA) test, digital rectal examination (DRE), and transrectal ultrasound. However, the gold standard for final diagnosis is the proper biopsy. In the clinical practice, the most frequently performed surgical method is transurethral resection of prostate (TURP). The problem lies in the fact that both malignant and benign lesions of the prostate have a very similar clinical presentation, but their management, awareness, prognosis, and follow-up are quite different. The routine DRE may not always be helpful for conclusion. A laboratory investigation that was previously linked to prostatic lesion is prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, in which increased levels were thought to be a good indication.[3] However, its significance is only complete when it is supported by histopathological study. Knowing the histological grade in malignant lesions helps in proper management and prognosis. Thus, diagnosis and grading of prostatic lesions are important to both, the clinicians and pathologists.

A prospective study was carried out at the department of pathology in a tertiary care center. A total of 119 cases of prostatic lesions were studied during July 2016–December 2016. Data were collected from biopsy and record department. The proper specimens were received and fixed in 10% formalin. The processed tissue was then stained with routine hematoxylin and eosin staining. All the specimens were analyzed as type of specimen, age of the patient, microscopic features, and diagnosis. The 2002 WHO classification was used to diagnose and classify prostate tumors. Gleason’s grading system was used for grading the cases of adenocarcinoma.[3]

Table 1 shows that the most common lesions diagnosed was BPH in 94 cases (79%), followed by seven cases of adenocarcinoma (6%) and least were five cases of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) (4%), five cases of stromal nodules of hyperplasia (4%), and five cases of atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) (4%). As per Table 2, majority of prostatic lesions (66) were seen in 51–60 years of age followed by 25 cases in 61–70 years of age. Six cases were noted in < 50 years and more than 80 years of age, respectively. Fifty-two cases (79%) of BPH were seen in the 6th decade (51–60 years) followed by 22cases (11%) in the 7th decade (71–80 years). For adenocarcinoma, all the cases were observed in the 6th decade (51–60years). Table 3 shows that prostatic-specific antigen (0–4 level) was most common in 66cases of prostatic lesion (57%) followed by 4.1–10.0 levels in 33 cases (29%). The most frequently seen PSA level was 0–4.0 in 60 cases (91%) of BHP followed by 4.0–10.0 in 26 cases (79%). In adenocarcinoma, the most common PSA level was >10.1 in 4 cases (57%) followed by 0–4.0 level in 2 cases (29%) and 4.0–10.0 level in 1 case (14%).

BPH on microscopy shows the glandular component made up of nodules of small and large acini lined by basal and secretory cells. Some glands show papillary infoldings and others are dilated and cystic and show corpora amylacea. Stromal component often shows both fibrous and smooth muscle elements [Figures 1 and 2]. A total of 79 (84%) cases also showed prostatitis. Only 8% of clinical incidence of BHP is seen during the 4th decade, but it reaches 50% by the 5th decade and progresses to 75% in the 8th decade of life.

Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of malignancy in the prostate and the glandular pattern observed under low power microscope is important as it is used for Gleason grading [Figure 3].[4] The most common score obtained was nine in three cases of a total of six adenocarcinoma cases.

PIN diagnosis is made when microscopically benign prostatic acini or ducts are lined by cytological atypical cells showing stratification and slight nuclear enlargement. In the current study, a total of five cases of PIN were diagnosed.

Stromal nodules of hyperplasia represent the smallest nodules of BPH that is often stromal and are composed of loose mesenchymal tissue and prominent small round vessels. Sometimes, TUR of prostate may contain extensive stromal BPH that can be misdiagnosed with stromal tumors of uncertain malignant potential.

AAH is a pseudoneoplastic lesion that can be confused with prostate adenocarcinoma due to its morphological features. PIN and AAH were assumed to be precursors of prostatic adenocarcinoma initially;[5] however, PIN now remains as the only well-proven preneoplastic condition with clinical significance. Nowadays, AAH is not considered a premalignant lesion but seen as a benign small glandular process. A localized proliferation of small acini within the prostate is AAH by definition. Such proliferations may be misdiagnosed as carcinoma. The glands with AAH have a fragmented basal layer. Three cases were inadequate for opinion as only occasional prostatic gland along with stroma was seen microscopically. For such cases, repeat biopsy was advised.

BPH and adenocarcinoma are two most common conditions affecting prostate gland. In the present study, we had 79% of cases of BPH, 6% of cases of adenocarcinoma, 4% of cases each of PIN, stromal nodules of hyperplasia, and AAH, respectively, and 3% of cases were inadequate. Similarly, Garg et al. reported that non-neoplastic prostatic tumor cases were of 78% followed by 21.7% of cases of adenocarcinoma.[6] Recently, higher incidence of neoplastic lesion was observed due to the diagnosis of prostate carcinoma at an early stage. Moreover, the study was carried out at tertiary health center. According to Ashish and Kaushal et al., majority of prostatic lesions were 61% of cases of BPH followed by 25% of cases of adenocarcinoma and 7% of case of HGPIN.[7] As per Jasani et al., the most common prostatic lesion was BPH 56% followed by adenocarcinoma 32%.[8]

In our study, majority of prostatic lesions (66) were seen in 51–60 years of age followed by 25 cases in 61–70 years of age and least six after 80 years of age. This is well known fact that prostate involvement mostly occurs after middle age. Similar study by Jasani et al. reported that the most common age group in prostatic lesions was 5th decade (51%) followed by the 6th decade (41%).[7] Garg et al. found that mean age in prostatic lesion was 68.6 years.[6]

The standard assessment to diagnose prostate cancer is DRE, PSA, and transurethral biopsy. The DRE has constantly been the primary method for evaluating the prostate. It is easy to conduct and cause little anxiety to the patient, but Smith and Catalona showed that the DRE depends on the investigator and has great interexaminer variability.[9] DRE is neither specific nor sensitive enough to identify prostate cancer and is unlikely to be improved.[10]

The frequency of the diagnosis of prostate malignancy has increased considerably since the introduction of PSA screening. As per Jasani et al., for diagnosis of BPH, mean PSA level is 4.86 ± 3.03; for adenocarcinoma, mean PSA level is 21.87 ± 14.7; and for PIN, mean PSA level is 9.26 ± 4.34.[7]

According to Wolf et al., the PSA and DRE may make false-positive or false-negative results, meaning that men without cancer may have abnormal outcome and get unnecessary additional testing, and clinically, important cancers may be missed.[11] False-positive results can lead to constant anxiety about prostate cancer risk. Abnormal results from screening with the PSA or DRE necessitate prostate biopsies to establish whether or not the abnormal findings are cancer. Biopsies can be painful, may lead to complications such as bleeding or infection, and can miss clinically important cancer. It is not necessary that all men whose prostate cancer is detected through screening require immediate treatment, but they may require periodic blood tests and prostate biopsies to determine the need. In our study, prostatic-specific antigen (0–4 level) 66 (57%) was the most common in prostatic lesion followed by (4.1–10.0 level) 33 (28%).

TURP was the most common type of specimen received for prostatic lesions. The majority of lesions are seen in the 6th decade of life. The most common prostatic lesion observed is BPH followed by prostatic adenocarcinoma. PIN presents as an important diagnostic challenge as they are known precursor lesions of prostatic carcinoma. PSA should be used for screening purpose, but its significance is only complete when it is supported by histopathological study. The most significant investigation for such cases is the biopsy of the prostate. Histopathological diagnosis and grading plays a definitive role in the proper management and prognosis of prostatic cancer. Hence, it is recommended to use the PSA test along with histopathological examination for prostate lesions, causing decrease in number of cases over the years, thus increasing the life span of males in our country.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.