Journal of Medical Sciences and Health

DOI: 10.46347/jmsh.2020.v06i03.013

Year: 2020, Volume: 6, Issue: 3, Pages: 79-81

Case Report

Sameena Khan1, Nikunja Das1, Rajashri Patil1, Shahzad Mirza1, Rabindra N. Misra2

1Assistant Professor, Department of Microbiology, D Y Patil Medical College and Hospital and Research, Dr D Y Patil Vidyapeeth, Pune, Maharashtra, India,

2Professor and Head, Department of Microbiology, D Y Patil Medical College and Hospital and Research, Dr D Y Patil Vidyapeeth, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Address for correspondence:

Sameena Khan, Kharadhi, Pune, Maharashtra, India. Phone: +91-9599679335. E-mail: [email protected]

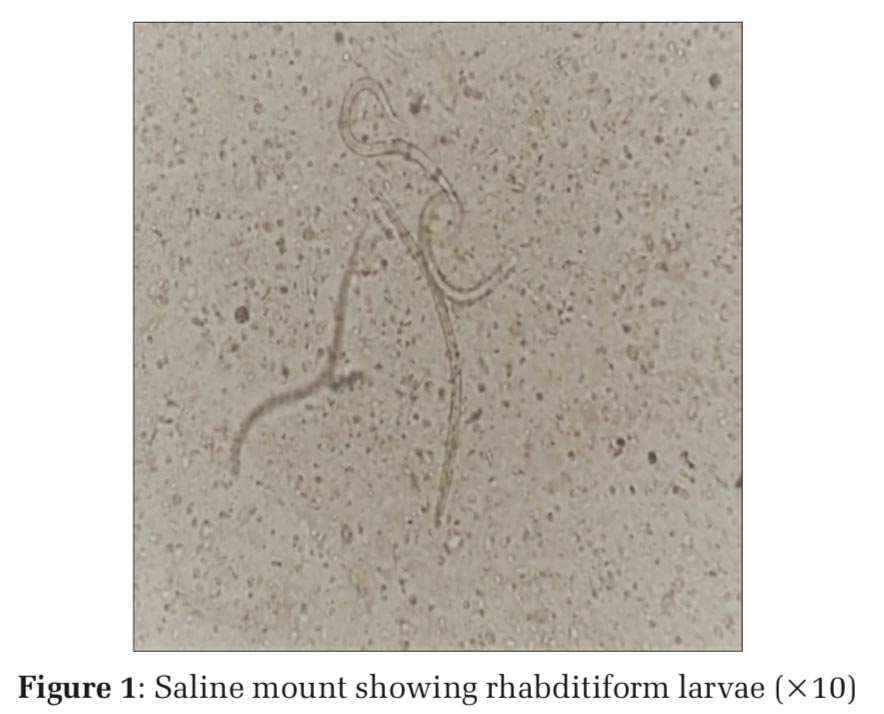

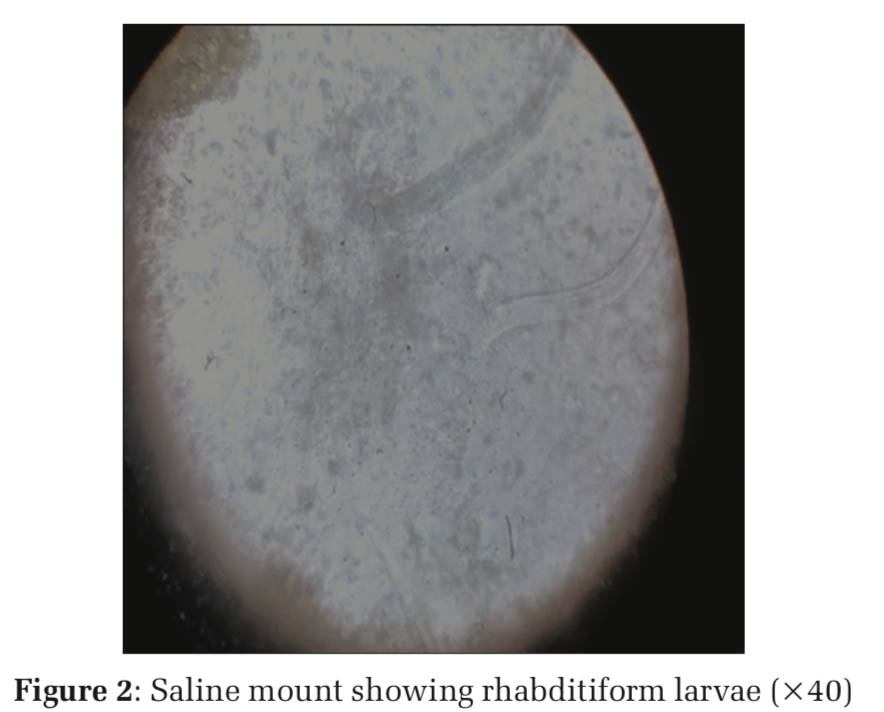

Strongyloides stercoralis, an intestinal nematode, is the major causative agent of Strongyloidiasis in humans. In immunosuppressed patients, infection with S. stercoralis can lead to the syndrome of hyper infection, which can lead to serious condition in rare cases. For prompt diagnosis, early identification of larvae in the stool sample is helpful. The current case report depicts an instance of Strongyloidiasis in a patient with Hansen’s infection. A 55-year-old elderly female patient reported with lepromatous infection and development of erythema nodosum leprosum and was undergoing treatment with thalidomide and prednisone for a decade. As the patient complained of vomiting and fever, a stool routine examination was done with saline and iodine mount which revealed plenty of rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis, identified by characteristic morphology. Early detection delays may be fatal and high levels of eosinophil might or may not always be elevated. She was treated with ivermectin (6 mg) in a double dose given 1 week apart which resulted in clearance of the larvae. The absence of infection was confirmed 3 times during follow-up by stool examination.

KEY WORDS: Strongyloides stercoralis, nematode, leprosy, immunocompromised.

Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode that causes gastrointestinal infections which are mainly asymptomatic. It is prevalent in tropical, subtropical regions, and also in certain zones of low- temperature endemicity.[1] S. stercoralis is a common cause of abdominal pain and diarrhea infecting about 100 million people around the world.[2] This parasite has a distinct lifecycle which includes direct, auto infective, and a non-parasitic free-living growth cycle.[3]

Human infections take place after contact with the soil, through the penetration of skin, usually of the feet, by infectious filariform larvae. The female parasite remains embedded in the small intestine’s submucosa and produces eggs by parthenogenesis without being fertilized by the male. The numbers of eggs are high and hatch in the host’s lumen, to form first second and third-stage larvae. The rhabditiform (first stage) larvae are either excreted in feces or become infective filariform (third stage) larvae or free living phase.

On the other hand, third-stage larva can develop inside the gastrointestinal tract and penetrate intestinal mucosa or perianal skin without even leaving their host and thus causing reinfection. The free adults sexually reproduce and the offspring become infective third-stage larvae.[4] Third-stage larvae penetrate the human host skin, reach through the blood circulation into the lungs and enter into the respiratory pathways, move up the trachea to be swallowed and finally reach the small intestine where they mature into adult egg- laying females.

Strongyloidiasis is classically identified through the detection of larvae in the stool.[5] However, because of its low parasite load and erratic larval development, S. stercoralis is the most difficult intestinal parasite to diagnose.[6]

Here, we report a case of a 55-year old female patient on steroid therapy for leprosy admitted in the skin ward with a history of fever and vomiting and was successfully treated with ivermectin.

A 55-year-old female, farmer, resident of a rural area in Maharashtra with borderline lepromatous leprosy presented to the hospital with high fever, vomiting, loss of appetite, and discharging lesion over left arm since 2 weeks. Over the past 10 years, she had been on multi-bacillary, multi-drug therapy, and intermittent doses of prednisolone and Thalidomide which she disclosed of taking irregularly. She eventually developed steroid-dependent erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) and neuritis and was, therefore, admitted to our hospital. She possessed typical characteristics such as moon faces, central obesity, pedal edema, and simple bruisability.

On examination, multiple red raised lesions over the body and discharging lesion on the left arm were found. Her blood pressure was 110/80 mm and pulse rate 84/min and temperature 99.9 F. Hemogram was significant for normocytic hypochromic anemia (hemoglobin 8.8 g/dL) and mild microcytosis with marked polymorphonuclear leukocytosis. Total iron-binding capacity) was low, high serum ferritin (846.16 μg/L) levels. C-reactive protein was positive (357.32) IU/ml and erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 109 mm/h. The patient showed normal eosinophil counts. HIV combo p24Ag, HIV 1 and HIV 2 antibody by chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay was nonreactive. Alkaline phosphate by p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate- kinetic was raised (187 u/Lt).

A routine stool examination was done as the patient had gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting. Fecal occult blood was positive. On macroscopic examination of stool specimen, it was found to be watery and brown in color with plenty of mucus. Microscopic examination of saline wet mount and Lugol’s iodine was done which showed numerous rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis. The parasites were identified with short mouth and double bulb esophagus [Figures1 and 2]. The patient was diagnosed with S. stercoralis infection for the 1st time, by the presence of S. stercoralis larvae in stool examination. She was treated with ivermectin (6 mg) in a double dose (given 1 week apart) which resulted in larvae excretion clearance. Steroids were stopped to allow clearance of the parasites. However,ifthereisariskofENLeruptionthenit must be continued in the lowest effective dose. Since this patient was on Thalidomide, prednisolone was stopped completely. The absence of infection was confirmed by stool examination done 3 times after 2 weeks of treatment.

Strongyloides have a distinct character among the common helminths, which allows them to survive and reproduce indefinitely and to complete their life span inside the human hosts. S. stercoralis infection causes no evident pathology in otherwise healthy individuals, which means many patients are undiagnosed and remain untreated for years. The host’s intestinal nematode tends to live with a risk of neighborhood and community infection. In immunocompromised patients, the disease can be more complicated and severe, with substantial public health consequences. The immunosuppression causes a propagation of the auto-infective process which makes eradication of this parasite difficult. Stool microscopy to identify S. stercoralis larvae or ova has variable sensitivity.[7] A direct stool microscopy has only a sensitivity of 30% and three specimens will increase the sensitivity to 60–70%.[7] The incidence of S. stercoralis infections is not much reported in many countries. It may be due to non- availability of most appropriate diagnostic tool and epidemiological data. Microscopic examination of direct saline and Lugol’s iodine mount of stool is widely used for the identification of helminths. However, diagnostic techniques such as Harada-Mori filter paper culture, Baermann technique, remain extremely sensitive in comparison to standard stool microscopy. Among immunocompetent hosts, peripheral eosinophilia of the blood is a constant finding related to strongyloidiasis.[8] However, because the immune response is blunted, patients on corticosteroids may lack eosinophilia. Eosinophilia is a good indicator, but cannot be predictive in patients with thalidomide.

Increasing follow-up and successful eradication should be considered in particular among immunocompromised people, as it may be silent for several years. In such patients, the host defenses are suppressed due to immunosuppressive medicines which cause T cell imporpedic function. Our patient was on long-term corticosteroid therapy and was diagnosed by routine examination of stool and was successfully treated by ivermectin (6 mg), on initiation of which, the stool sample was negative for S. stercoralis larvae. Three sample exams were used to confirm the treatment with ivermectin which led to larvae excretion clearance.

Strongyloidiasis is the major health concern in many countries around the world, and hence stool samples should be screened carefully for the presence of larvae before and at some stage in corticosteroid treatment. Untreated infections in certain subgroups of the population may cause significant community problems with the likelihood of Strongyloidiasis evolving into severe invasive disease. In patients from endemic areas for Strongyloidiasis, ivermectin should be given as prophylaxis when initiating multidrug therapy for leprosy and in patients at risk on long-term steroids. Detailed research, prompt diagnosis, and routine screening of stools, and adequate care would minimize deaths and protect the patient from complications, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Subscribe now for latest articles and news.